HISTORY of the firm

The Forebears of Robert Morton

The Robert Morton Organ Company was the final incarnation of a series of companies which changed their names in the boardrooms and the charters of the enterprise, but had a much lesser effect on the factory and personnel of the firm. If there was a common thread running through the various incarnations of the business, it was certainly chronic financial instability. And yet, in spite of the financial ordeals at each level of the company, it managed to stay in business and produce many excellent instruments through the course of its existence.

The Murray M. Harris Organ Company

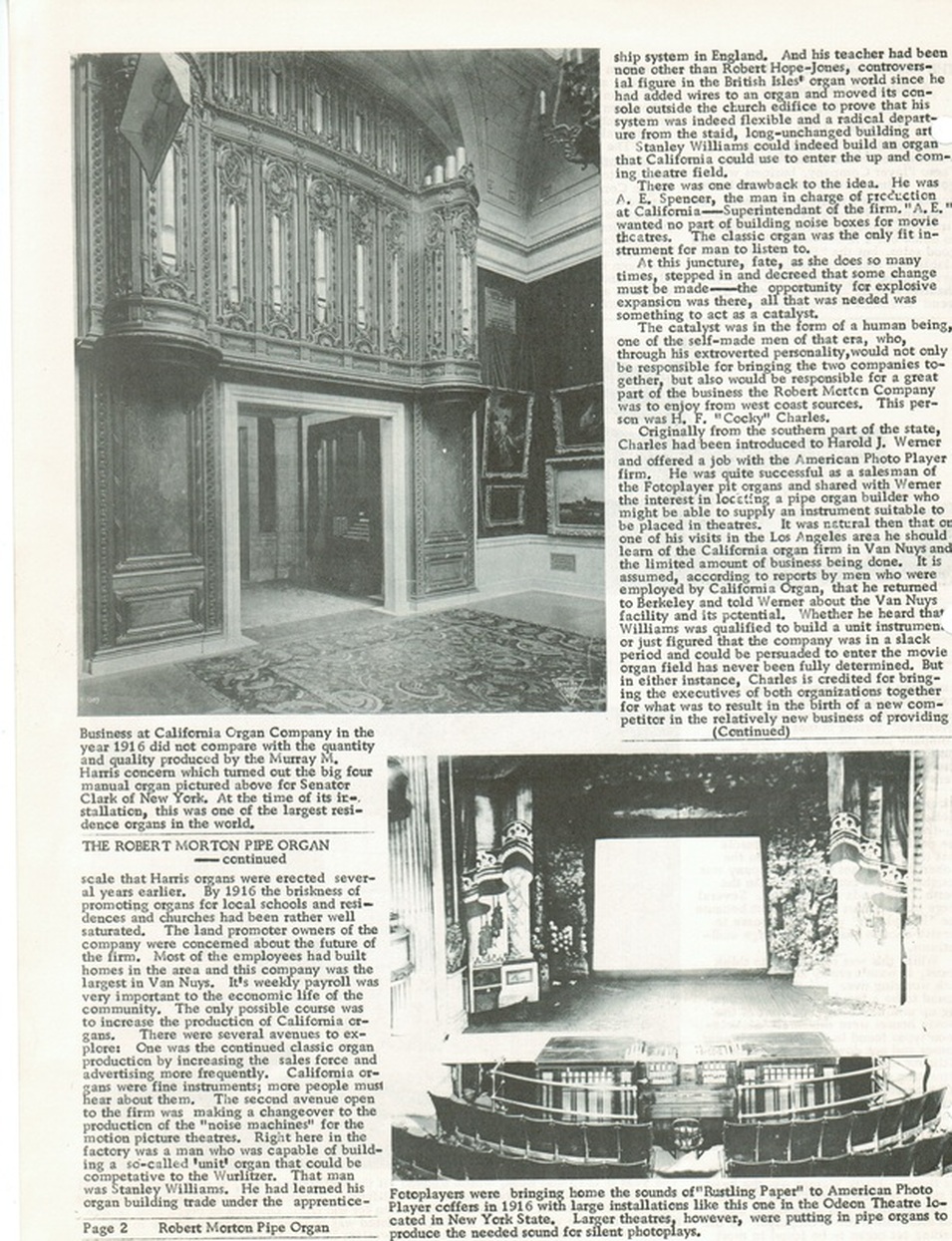

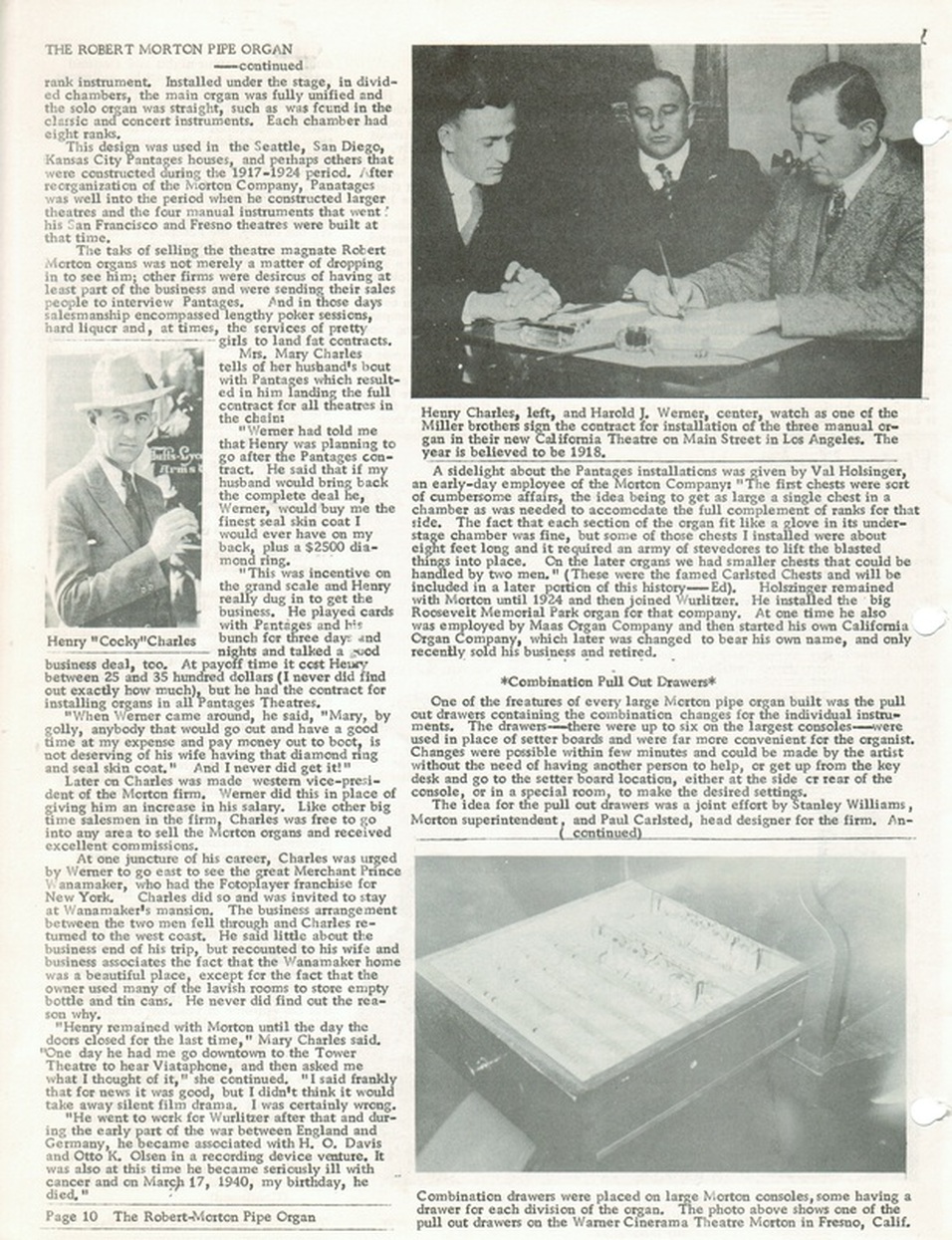

PHOTO I

The inauguration of this "expedition" occurred with the birth of the Murray M. Harris Organ Company in 1900, although Murray M. Harris had been involved in organ building in California since 1894 (1 : 26). As has happened with many organ-building firms, the M.M. Harris Organ Company crossed an artistic and financial Rubicon when it undertook the contract to build a massive organ for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, an instrument designed by George Audsley and consisting of 140 stops (1 : 60) controlled by a five-manual console. At the time, this was the largest pipe organ project ever undertaken by an organ builder anywhere in the world (1 : 44).

With production on the huge instrument underway, by the summer of 1903 the company was in significant financial difficulty, and the stockholders became very dissatisfied with Harris' leadership. He was voted out of the presidency of the company in August of 1903

(1 : 44). In January of 1904, the name of the company was changed to "Los Angeles Art Organ Company" (1 : 46). In this form, the firm continued through 1905, but ultimately found that along with litigation troubles involving the Aeolian Organ Company, the deficits incurred in building the world's largest pipe organ were fatal (1 : 63), and the firm once again found itself in dire straits.

A number of employees defected to an east coast company, the Electrolian Organ Company, started up by William B. Fleming (who later headed up the Wanamaker organ shop), the former Murray M. Harris factory superintendent. Unfortunately, this company did not do well, and by 1906, many of those former employees began to gravitate back to Los Angeles. Interestingly, Fleming himself became associated with the Wanamaker department store in Philadelphia, where he became the shop superintendent in charge of the installation and enlargement of the 1904 Exposition organ in the Grand Court of the Philadelphia store.

In 1906, the Murray M. Harris Company was reorganized by Harris in Los Angeles, and this firm managed to draw back many of the employees of the earlier Harris firm and the Los Angeles Art Organ Company. This incarnation remained in business, producing some very large and fine organs under this name until 1913 (1 : 81). From 1908, Murray M. Harris himself played a smaller and smaller role in the management of the firm, and by 1913, he had largely left the firm for other pursuits. By 1912, it became apparent that the company was once again in financial decline.

In these dark times, an opportunity then presented itself. During 1913, it was decided that the factory operations in Los Angeles would be moved to Van Nuys, California, in the then-undeveloped San Fernando Valley. This move was encouraged by landed investors (Suburban Homes Company) in the valley, who offered nine acres upon which to build a plant, as well as other financial incentives (1 : 84). The thought was that if industries could be built in the valley, homes for the workers would follow, benefiting Suburban Homes.

Construction started on the new factory building in early 1913, but by October, the name of the company had changed once again.

With production on the huge instrument underway, by the summer of 1903 the company was in significant financial difficulty, and the stockholders became very dissatisfied with Harris' leadership. He was voted out of the presidency of the company in August of 1903

(1 : 44). In January of 1904, the name of the company was changed to "Los Angeles Art Organ Company" (1 : 46). In this form, the firm continued through 1905, but ultimately found that along with litigation troubles involving the Aeolian Organ Company, the deficits incurred in building the world's largest pipe organ were fatal (1 : 63), and the firm once again found itself in dire straits.

A number of employees defected to an east coast company, the Electrolian Organ Company, started up by William B. Fleming (who later headed up the Wanamaker organ shop), the former Murray M. Harris factory superintendent. Unfortunately, this company did not do well, and by 1906, many of those former employees began to gravitate back to Los Angeles. Interestingly, Fleming himself became associated with the Wanamaker department store in Philadelphia, where he became the shop superintendent in charge of the installation and enlargement of the 1904 Exposition organ in the Grand Court of the Philadelphia store.

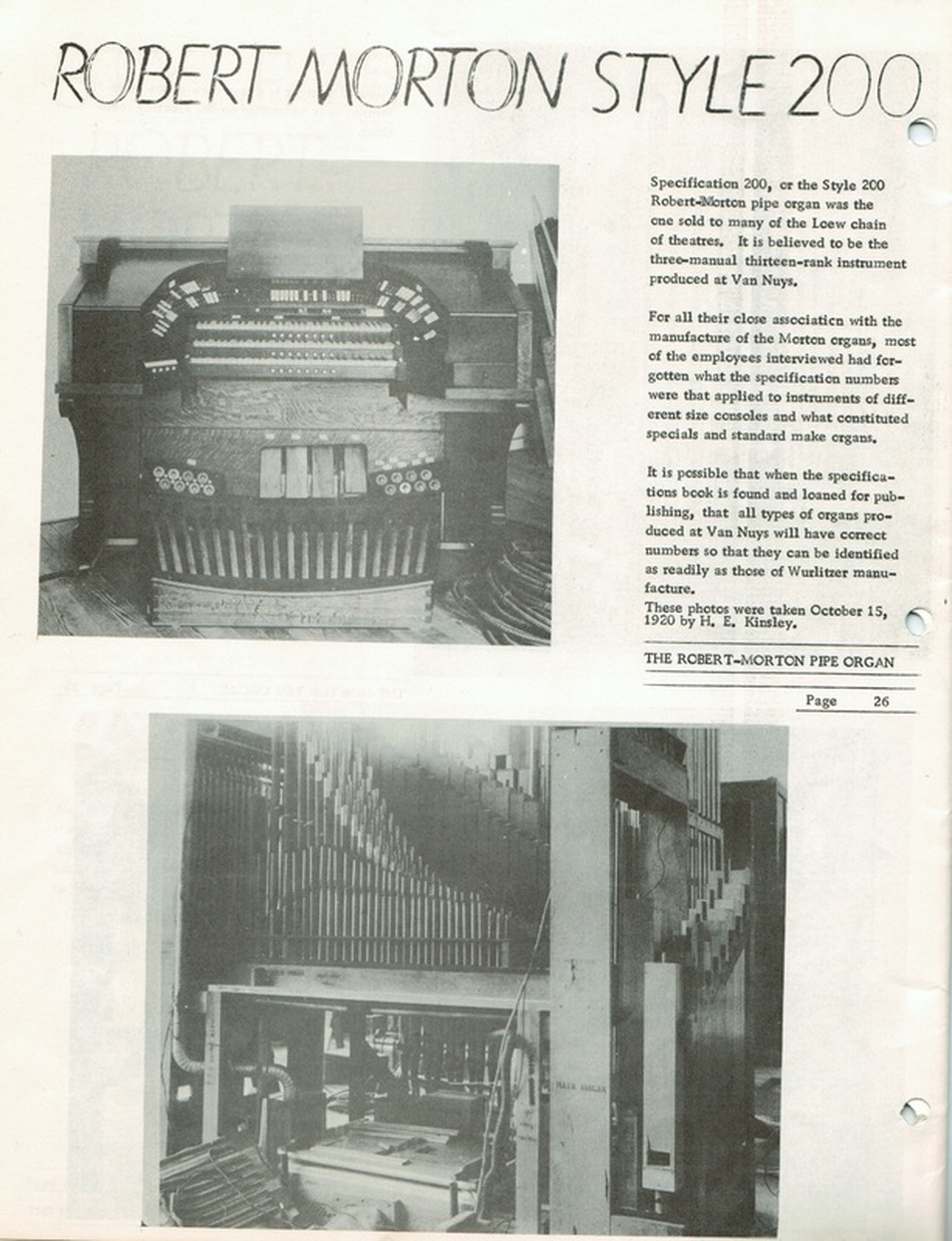

In 1906, the Murray M. Harris Company was reorganized by Harris in Los Angeles, and this firm managed to draw back many of the employees of the earlier Harris firm and the Los Angeles Art Organ Company. This incarnation remained in business, producing some very large and fine organs under this name until 1913 (1 : 81). From 1908, Murray M. Harris himself played a smaller and smaller role in the management of the firm, and by 1913, he had largely left the firm for other pursuits. By 1912, it became apparent that the company was once again in financial decline.

In these dark times, an opportunity then presented itself. During 1913, it was decided that the factory operations in Los Angeles would be moved to Van Nuys, California, in the then-undeveloped San Fernando Valley. This move was encouraged by landed investors (Suburban Homes Company) in the valley, who offered nine acres upon which to build a plant, as well as other financial incentives (1 : 84). The thought was that if industries could be built in the valley, homes for the workers would follow, benefiting Suburban Homes.

Construction started on the new factory building in early 1913, but by October, the name of the company had changed once again.

The Move to Van Nuys

Although still incorporated under the Murray M. Harris name, plans were made to move the plant from downtown Los Angeles to the San Fernando Valley in a budding community called Van Nuys, created by the Los Angeles Suburban Homes Company, a real estate developer. The principals of the developer persuaded the Harris Company to relocate to Van Nuys with both financial guarantees and over nine acres of land for a factory. The developer's idea was to create industries in the valley that would provide jobs for people, who would then purchase homes from the developer.

Interestingly, the factory was built and opened under the Johnston Organ and Piano Manufacturing Company banner, rather than Murray M. Harris. The Harris enterprise, once again in financial trouble had changed hands, with Murray Harris himself finally leaving the organ business for good.

Interestingly, the factory was built and opened under the Johnston Organ and Piano Manufacturing Company banner, rather than Murray M. Harris. The Harris enterprise, once again in financial trouble had changed hands, with Murray Harris himself finally leaving the organ business for good.

The Johnston Organ & Piano Manufacturing Company

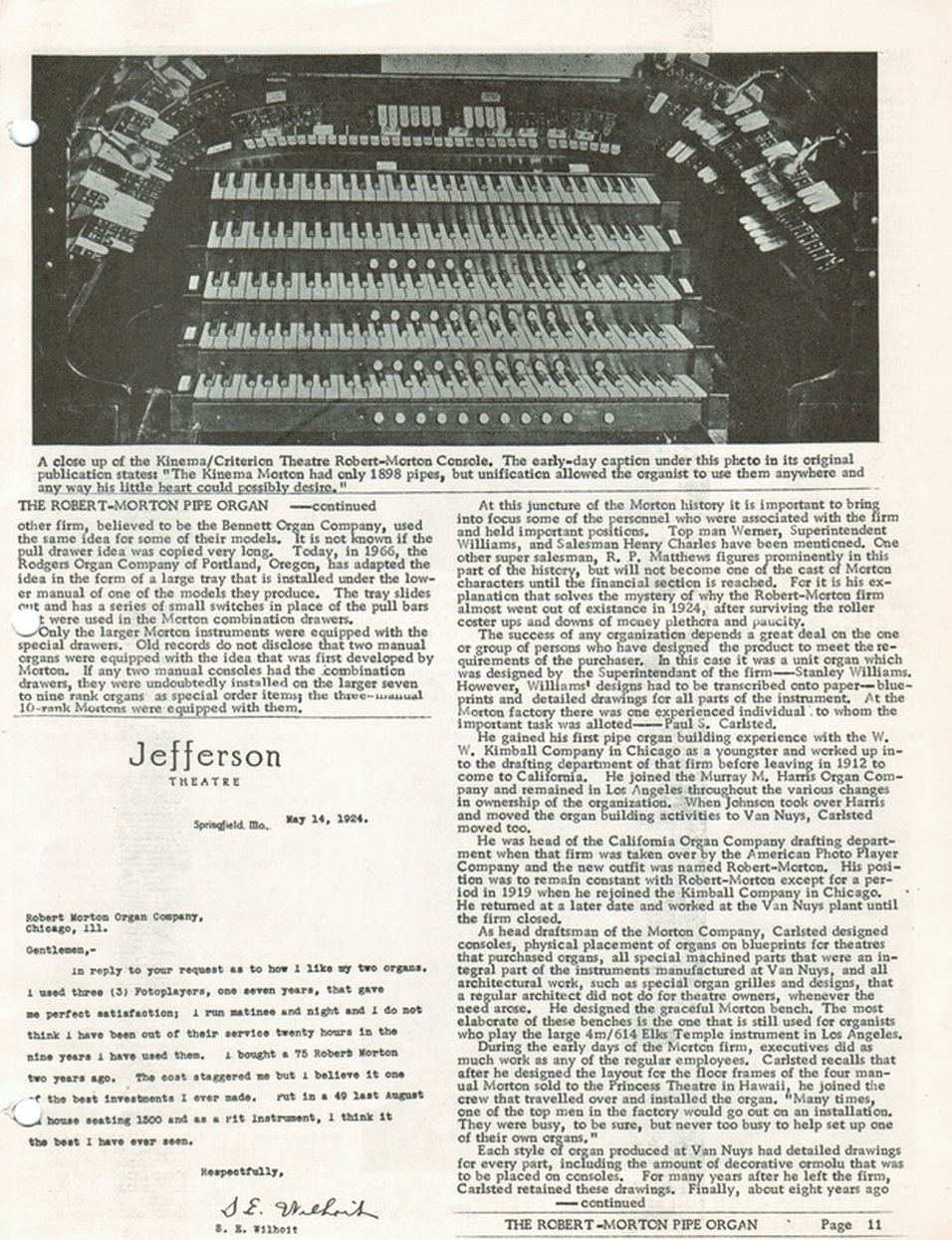

PHOTO II

The "Johnston Organ & Piano Manufacturing Company" featured Mssrs. E.S. Johnston and P. Bell in the executive capacity, former employees of the Eilers Music Company who had purchased their interests in the company from a major Harris stockholder and officer (1 : 83). During this period (1913-14) organs were sold under both the Harris nameplate and the Johnston nameplate, although they were produced by the same craftsmen at the same factory (1 : 84).

Although Johnston was an aggressive salesman, the two were not able to raise sufficient capital to ensure the company's continued existence, and in fact their investors became concerned about their haphazard (and perhaps slightly "shady") style of management.. Disappointed and frustrated with this state of affairs, Suburban Homes took over the firm (which they had largely been bankrolling) and turned its operations over to the Title Insurance & Trust Company (1 : 85) by 1914. Sometime between August 1915 and February 1916, the firm was renamed the "California Organ Company", and basically specialized in traditional church pipe organs.

Although Johnston was an aggressive salesman, the two were not able to raise sufficient capital to ensure the company's continued existence, and in fact their investors became concerned about their haphazard (and perhaps slightly "shady") style of management.. Disappointed and frustrated with this state of affairs, Suburban Homes took over the firm (which they had largely been bankrolling) and turned its operations over to the Title Insurance & Trust Company (1 : 85) by 1914. Sometime between August 1915 and February 1916, the firm was renamed the "California Organ Company", and basically specialized in traditional church pipe organs.

The California Organ Company

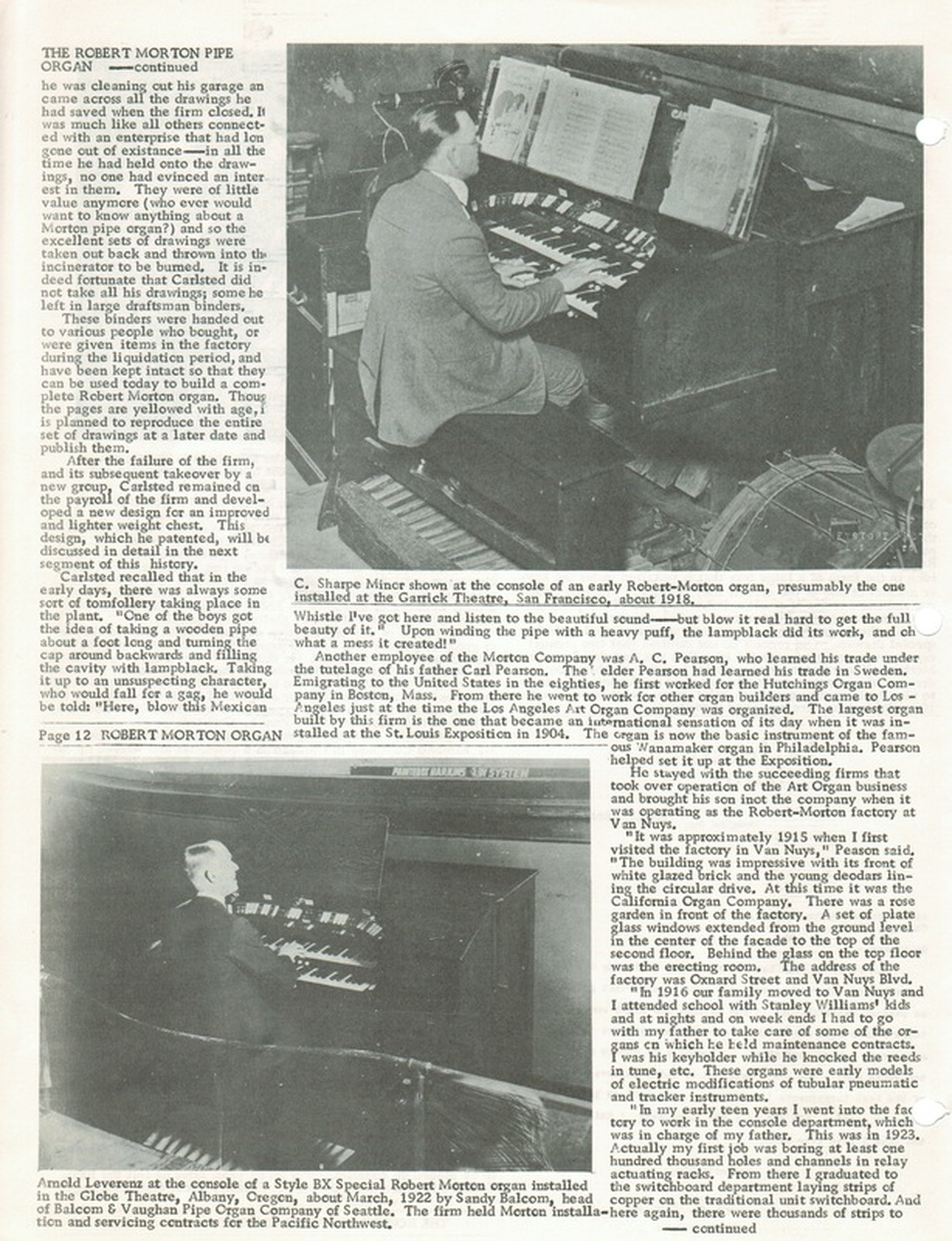

PHOTO III

Although initially the California Organ Company was owned by the real estate developer, Suburban Homes, the developers were not really interested in running a pipe organ manufacturing business. They earnestly sought out a potential buyer who could run the company successfully, thus insuring the stability of the jobs generated by the company (and the ability of its employees to pay their mortgages).

During this relatively short period, the California Organ Company continued to manufacture organs, a number of which are still extant in Los Angeles high school auditoriums in Van Nuys, Reseda, Redondo Beach and Canoga Park, to name a few (see Owensmouth HS auditorium, above left, and Van Nuys HS auditorium, below). The firm also built organs, some quite large for many local churches.

A.E. Spencer, the factory superintendent for the Murray M. Harris firm, remained superintendent during the Johnston and California Organ years. In 1916, R.P. Elliot, the former president of the Hope-Jones Organ Company in Elmira, joined the firm as vice president and general manager (2 : 495). Most of California Organ's output was destined for the church trade, with several instruments going into schools and residences, and even a few organs going into theatres. These "theatre organs", however, were basically church instruments, as were many of the organs that first found their way into American theatres. By 1915, Wurlitzer began to change that dynamic; radically.

During this relatively short period, the California Organ Company continued to manufacture organs, a number of which are still extant in Los Angeles high school auditoriums in Van Nuys, Reseda, Redondo Beach and Canoga Park, to name a few (see Owensmouth HS auditorium, above left, and Van Nuys HS auditorium, below). The firm also built organs, some quite large for many local churches.

A.E. Spencer, the factory superintendent for the Murray M. Harris firm, remained superintendent during the Johnston and California Organ years. In 1916, R.P. Elliot, the former president of the Hope-Jones Organ Company in Elmira, joined the firm as vice president and general manager (2 : 495). Most of California Organ's output was destined for the church trade, with several instruments going into schools and residences, and even a few organs going into theatres. These "theatre organs", however, were basically church instruments, as were many of the organs that first found their way into American theatres. By 1915, Wurlitzer began to change that dynamic; radically.

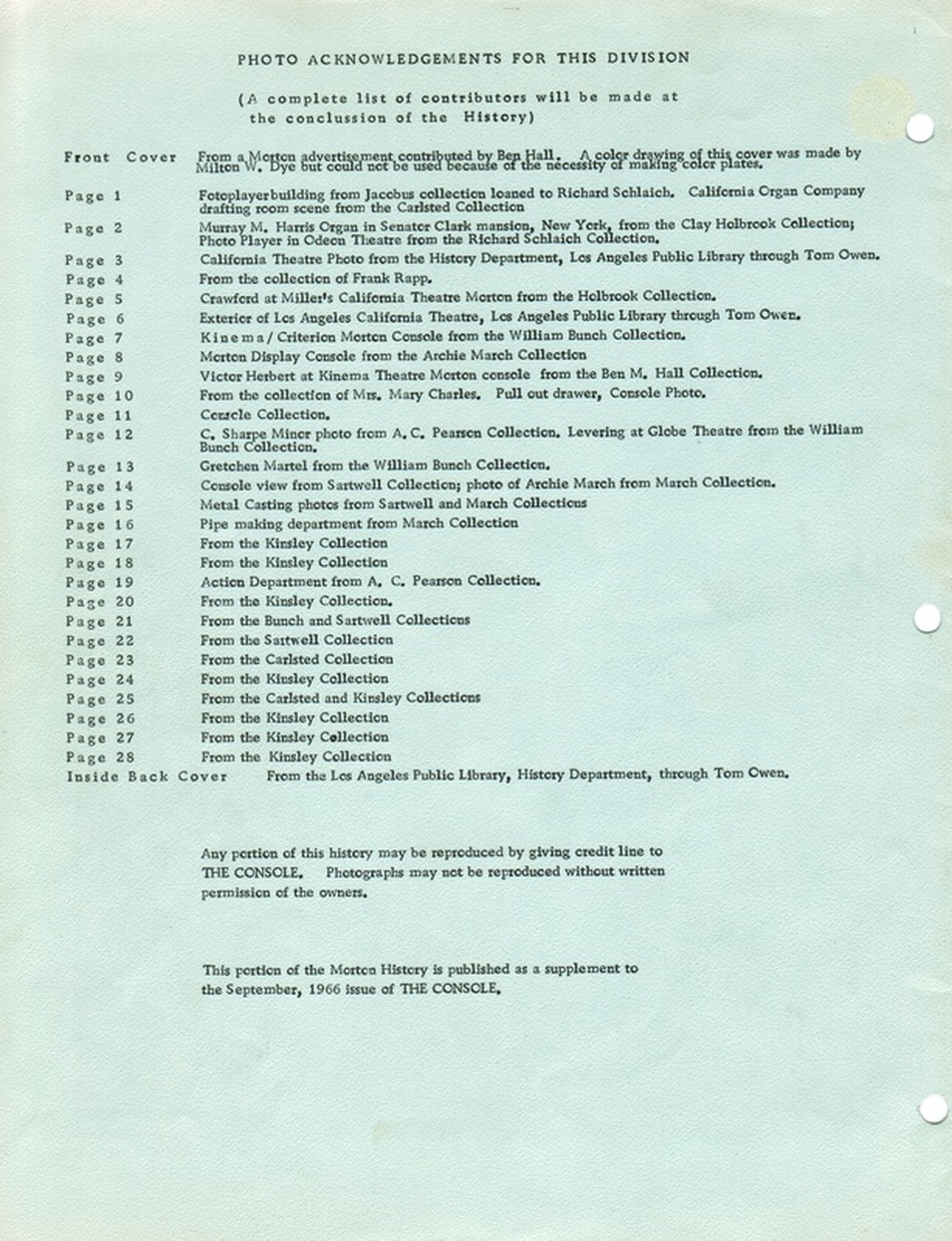

The American Photo Player Company

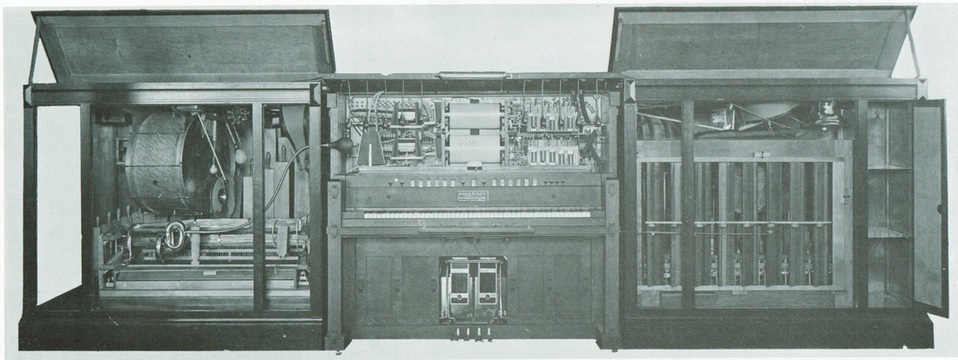

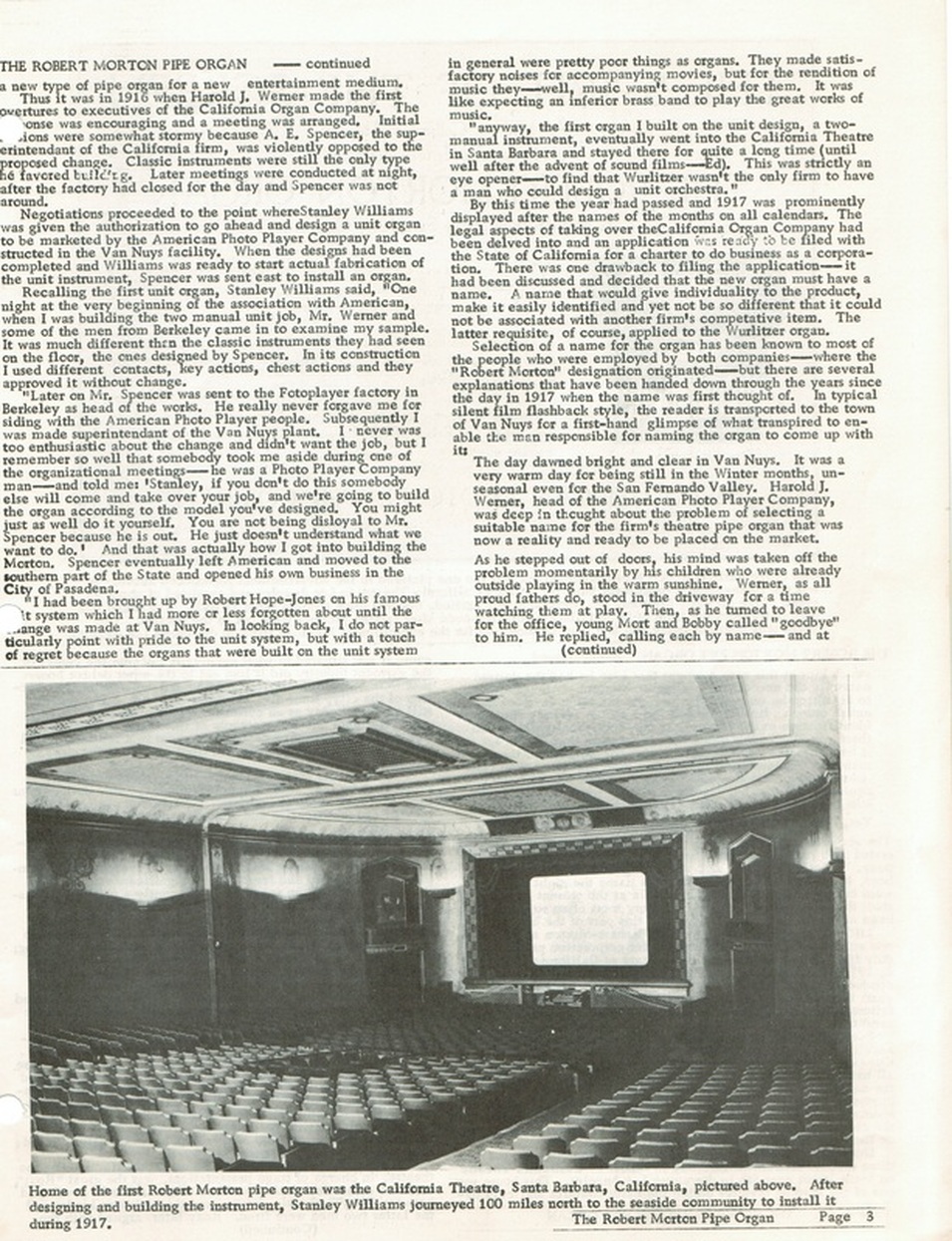

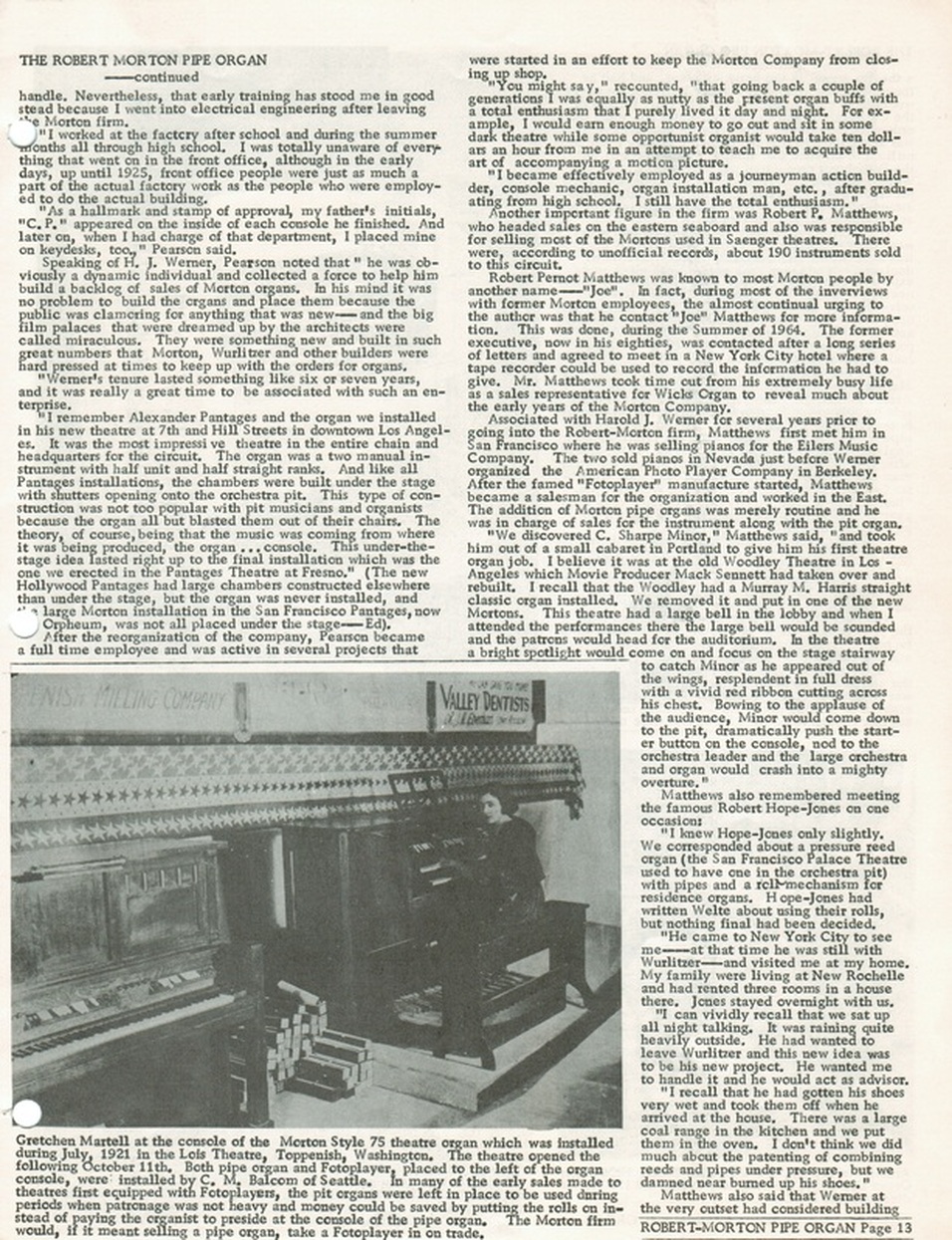

PHOTO V

In the early days of the silent film, patrons usually had to rely upon an upright piano for musical accompaniment. If they were lucky, it came with a pianist instead of a roll player. A number of firms became aware that there was a growing market for instruments that surpassed pianos in their ability to create both music and special effects. More costly than a simple piano, but much less expensive than a church organ (which were really the first theatre organs), they could deliver a broader spectrum of colors and surprises to accompany the film on the screen and delight moviegoers.

As America entered the 'teens, the silent movie exhibition business had left its roots in arcades and nickelodeons, and blossomed into a major industry, spurring the construction of purpose-built theatres. And while many small venues continued to use pianos, more and more smaller theatres could afford to install pit organs -- instruments which combined a piano, pipes, percussions and traps into the crude forebear of the theatre organ to come. (please refer to the picture below; a Style 40 Fotoplayer).

One of the most successful producers of these instruments was the American Photo Player Company, producer of the "Fotoplayer" brand., Located in Berkeley, California., its president, Harold J. Werner, was aware of the sales potential in providing full sized pipe organs for the ever larger theatres being built. Werner became interested in following Wurlitzer's lead in producing full-size pipe organs with the accoutrements of the Fotoplayer units. But the Berkeley factory wasn't set up for such work, and he cast about for a facility that could do such large scale production work. Werner was steered towards the California Organ Company in Van Nuys by Henry "Cocky" Charles, one of Photoplayer's premier salesmen. (4 : 1) (1 : 85). The facility had a sprawling plant outfitted for pipe organ production, a large erecting room, and was close to major rail lines. It was perfect for transformation into a major production facility for theatre organs. In 1916, Werner approached the hapless owners of the California Organ Company (whom you will recall did not really want to be in the organ business at all) and began negotiations for acquiring the firm.

There was resistance from within California Organ Company, however; most notably from the plant superintendent, A.E. Spencer, who had no use for the new "theatrical" style of instrument. In an effort to smooth the process, meetings were arranged at night, after Spencer had left for the day. It was at this time that Werner became aware that the company did have a man who could produce the kind of instrument he was looking for -- Stanley Williams, the firm's chief voicer, and a former protege' of Robert Hope-Jones in England. He was called upon to create a prototype for a theatre organ, using unification and a selection of stops appropriate to the genre'. While Spencer was sent off to supervise the installation of an organ in the east, Williams set about creating what was to be the first Robert Morton theatre organ. (4 : 3)

American Photo-Player had started a subsidiary in 1915, called the American Pipe Organ Company, and E.A. Spencer was assigned as the superintendent of that work in Berkeley, California. American Pipe Organ Company apparently produced some number of pipe organs, although little information has surfaced about this offshoot of the main company. This move, however, cleared the way for theatre organ production in Van Nuys.

It was just what Werner was looking for, and it sealed the fate of the California Organ Company. Through 1916 and into 1917, steps to acquiring the firm were taken, culminating in the purchase and incorporation of a new company. The acquisition of California Organ Company gave them the manufacturing power they needed, and Photoplayer's offices in New York, St. Louis and San Francisco provided ready, national sales offices from which to build the identity of the Robert-Morton organ. The American Photo Player Company, now the parent company of Robert-Morton, had finally relieved the real estate developers of their burdensome white elephant, and paved the way for the creation and production of the Robert Morton theatre pipe organ.

As America entered the 'teens, the silent movie exhibition business had left its roots in arcades and nickelodeons, and blossomed into a major industry, spurring the construction of purpose-built theatres. And while many small venues continued to use pianos, more and more smaller theatres could afford to install pit organs -- instruments which combined a piano, pipes, percussions and traps into the crude forebear of the theatre organ to come. (please refer to the picture below; a Style 40 Fotoplayer).

One of the most successful producers of these instruments was the American Photo Player Company, producer of the "Fotoplayer" brand., Located in Berkeley, California., its president, Harold J. Werner, was aware of the sales potential in providing full sized pipe organs for the ever larger theatres being built. Werner became interested in following Wurlitzer's lead in producing full-size pipe organs with the accoutrements of the Fotoplayer units. But the Berkeley factory wasn't set up for such work, and he cast about for a facility that could do such large scale production work. Werner was steered towards the California Organ Company in Van Nuys by Henry "Cocky" Charles, one of Photoplayer's premier salesmen. (4 : 1) (1 : 85). The facility had a sprawling plant outfitted for pipe organ production, a large erecting room, and was close to major rail lines. It was perfect for transformation into a major production facility for theatre organs. In 1916, Werner approached the hapless owners of the California Organ Company (whom you will recall did not really want to be in the organ business at all) and began negotiations for acquiring the firm.

There was resistance from within California Organ Company, however; most notably from the plant superintendent, A.E. Spencer, who had no use for the new "theatrical" style of instrument. In an effort to smooth the process, meetings were arranged at night, after Spencer had left for the day. It was at this time that Werner became aware that the company did have a man who could produce the kind of instrument he was looking for -- Stanley Williams, the firm's chief voicer, and a former protege' of Robert Hope-Jones in England. He was called upon to create a prototype for a theatre organ, using unification and a selection of stops appropriate to the genre'. While Spencer was sent off to supervise the installation of an organ in the east, Williams set about creating what was to be the first Robert Morton theatre organ. (4 : 3)

American Photo-Player had started a subsidiary in 1915, called the American Pipe Organ Company, and E.A. Spencer was assigned as the superintendent of that work in Berkeley, California. American Pipe Organ Company apparently produced some number of pipe organs, although little information has surfaced about this offshoot of the main company. This move, however, cleared the way for theatre organ production in Van Nuys.

It was just what Werner was looking for, and it sealed the fate of the California Organ Company. Through 1916 and into 1917, steps to acquiring the firm were taken, culminating in the purchase and incorporation of a new company. The acquisition of California Organ Company gave them the manufacturing power they needed, and Photoplayer's offices in New York, St. Louis and San Francisco provided ready, national sales offices from which to build the identity of the Robert-Morton organ. The American Photo Player Company, now the parent company of Robert-Morton, had finally relieved the real estate developers of their burdensome white elephant, and paved the way for the creation and production of the Robert Morton theatre pipe organ.

The Robert-Morton Organ Company

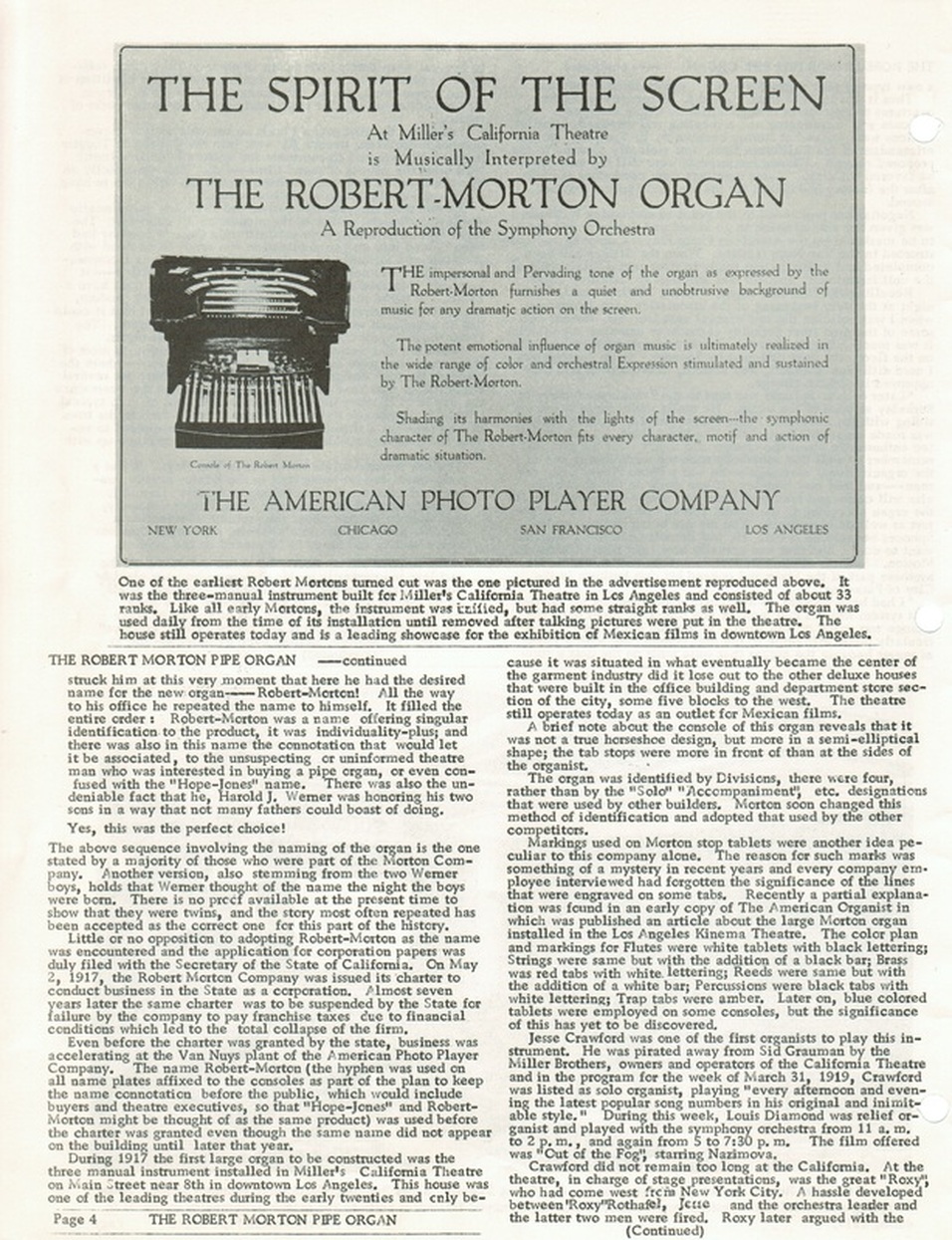

PHOTO VII

In the final name change of the expedition, the Robert-Morton Organ Company was incorporated on May 2, 1917. The factory stayed the same, but the name over the door changed, as did the mission of the company.

The American Photo Player Company continued to produce Fotoplayers in its Berkeley facility, but Robert Morton was tasked with building larger theatre pipe organs, and church organs, with an aim to rival the famed Wurlitzer in quality and quantity. The advantage to American Photoplayer was twofold: if a salesman couldn't make a case to a small theatre for a four or five rank Robert-Morton, he could then "trade down" to a Fotoplayer Pit Organ, or vice-versa. The products were not in conflict, and could even be seen as a "continuum", a way of providing the instrument that was the perfect fit for a theatre, be it a humble neighborhood house, or a downtown movie palace.

It is worth mentioning that although the production of theatre organs was the prime motivator in acquiring the California Organ Company, money was the supreme motivation for all production. The firm continued to turn out church organs in significant numbers, and this continued until the day the factory doors closed for good.

The Robert Morton Name

At the time that the Robert Morton Organ Company entered the theatre organ business in 1917, Wurlitzer was the heavy-hitter in the industry, having basically (through Robert Hope-Jones) invented the form of the instrument. Thus the "horseshoe" console, unification, tremulants, percussions and traps were already de rigeur for a theatre organ. Because of its association as a subsidiary of the American Photoplayer Company in Berkeley, much of this technology was already in use within the company, and merely had to be incorporated into the Robert Morton product.

In terms of marketing, the company wisely decided that it would attempt to ride Wurlitzer's coat-tails, and perhaps sow some brand confusion for prospective customers. In selecting the name Robert-Morton, the company's operators were attempting to draw a parallel to the Hope-Jones name, thus the hyphen.

There was no employee or owner of the company who was named "Robert Morton". The most common story of the origins of the Robert-Morton is apocryphal, but it is a story that tells well and so has usually been accepted at face value:

"The day dawned bright and clear in Van Nuys. It was a very warm day for being still in the Winter months, unseasonal even for the San Fernando Valley. Harold J. Werner, head of the American Photo Player Company, was deep in thought about the problem of selecting a suitable name for the firm's theatre pipe organ that was now a reality and ready to be placed on the market.

"As he stepped out of doors, his mind was taken off the problem momentarily by his children who were already outside playing in the warm sunshine. Werner, as all proud fathers do, stood in the driveway for a time watching them at play. Then, as he turned to leave for the office, young Mort and Bobby called "goodbye" to him. He replied, calling each by name -- and it struck him at this very moment that here he had the desired name for the new organ -- Robert-Morton!

"All the way to his office he repeated the name to himself. It filled the entire order: Robert-Morton was a name offering singular identification with the product, it was individuality-plus; and there was also in this name the connotation that would let it be associated, to the unsuspecting or uninformed theatre man who was interested in buying a pipe organ, or even confused with the "Hope-Jones" name.

"There was also the undeniable fact that he, Harold J. Werner, was honoring his two sons in a way that not many fathers could boast of doing."

(4 : 3-4)

This makes for a nice story and is almost accurate, but without question the more likely source of the name is cited in Dr. Ochse's excellent book about the Murray M. Harris firm:

"Census reports of 1920 confirm that Harold J. Werner had three sons: Harold J. (b. 1913), Robert M. (b.1916), and Richard P. (b. 1918). Negotiations for the sale of the California Organ Company to Werner and organization of the new company took place near the time of Robert M.'s birth on May 15, 1916, a coincidence that probably explains the choice of name. Robert M. himself used the name of Mort Werner." (1 : 86)

So, instead of dividing the honor between two sons, Harold Werner bestowed it upon his most recently-arrived progeny, giving the company his new-born son's name -- with a hyphen. . .

Of course, as their product's reputation blossomed, and the cache' of Robert Hope-Jones' name decreased, eventually the Wurlitzer Company eliminated the references to Hope-Jones in their advertising and marketing, and dropped his name from their builder's plates.

Robert Morton used the hyphen on their nameplates until around 1923 to 1924, when they adopted the brass, shield-shaped plate that is most familiar to us now. During the tenure of the firm, however, they used a variety of nameplates, some of which were specific to the location of the factory where the organ was built.

A POSTSCRIPT --

On April 17, 1990, Robert Morton Werner, "a television producer and the head of programming at NBC from 1960 to 1972, died of kidney failure. . .at Kula Hospital on Maui, Hawaii, after a long illness. He was 73 years old and lived in Pukalani, on Maui." Mr. Werner, who was known as "Mort", joined NBC in 1952 as a producer of the "Today" show. He later produced the "Tonight" show with Jack Paar, and introduced such shows as "Bonanza", "Star Trek" and "Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In". In the early 1960's , he served as president of the American Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. Mort Werner was 73 in 1990, which indicates that he was born in 1917 -- the year that the Robert Morton Organ Company was christened with his name. (6 : internet NYT)

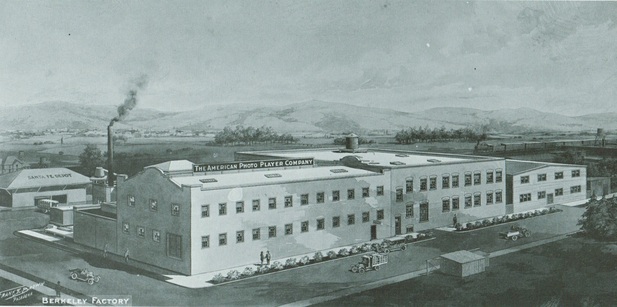

the meltdown of 1924

Mortimer Fleishhacker

Mortimer Fleishhacker

The fledging Robert-Morton Organ Company went through periods of feast and famine in its early days, with the factory sometimes shutting down for a few weeks, or occasionally a month or two. There were certainly orders for theatre organs coming in, but the firm lacked "fluidity" -- operating capital to buy materials and make payroll. During these periods, employees would frequently find temporary jobs elsewhere, and the top employees in the firm (even semi-management) would go off to work for other organ companies. For instance, during one of these hiatus periods, draftsman and designer Paul Carlsted even went back to work for the Kimball organ company for a few months. But when Robert Morton's doors opened again, he resumed his duties without fail.

On June 15, 1919, the factory closed for a significant period of time, opening again in October (4 : 21).

But the greatest dispruption came in 1923 / 1924, when the State of California suspended Robert Morton's charter of incorporation on March 19, 1924, (4 : 23) for failure to pay franchise taxes. (4 : 4) This apparently happened because of a sudden dearth of funds which was provoked by a serious charge -- hypothecation of contracts by the firm. The charges were specifically leveled at H.J. Werner, who was accused of "selling organs in the East, obtaining the money for them and then pledging the contracts again in the West to get additional money" (4 : 21) Essentially, an organ would be sold, the money paid to the company, and then the contract for that organ would be taken to a bank and used for collateral on a loan for the value of the contract, which is an act of criminal fraud.

Ultimately, it was determined that Werner had committed no fraud, but had managed the company's finances so carelessly that most of the time it teetered on the brink of insolvency.

Rumors to this effect began to circulate in banking circles, although few at the company were aware of what was going on. Stanley Williams was made aware of the problems by R.P. Elliott, who persuaded him to come work for the Kimball Organ Company. Williams submitted his resignation in 1923, less than a year before the meltdown. Robert Morton's stockholders and creditors, however, also become aware and this produced a stockholder lawsuit against Robert Morton and H.J. Werner. This forced the company into receivership in mid-1923, and ultimately resulted in the complete reorganization of the company, which became The Photo Player Company. This blanket name applied to both the American Photo Player Company and the Robert Morton Organ Company, although organs continued to be produced bearing the Robert Morton nameplate. In fact, most of the company's employees didn't notice much of a difference during this stormy period for management of the company. (

Werner was removed from the company, and replaced by James A.G. Schiller, who was appointed as general manager. Schiller was no organ man, but was a good businessman and organizer, and in a short period of time he made changes in the organization that even the employees on the factory floor could see and appreciate. As noted by Paul Carlsted, Schiller "turned the plant upside down [and] surprisingly enough he got everything organized on a plan and it went along much better" (2 : 500) Casting about for backers, the company found the ideal financial support from San Francisco banker and businessman, Mortimer Fleischacker, president of the Anglo-California Trust Company in that city. 2 : 500, 4 : 23) From this point onward, Robert Morton had no more financial problems.

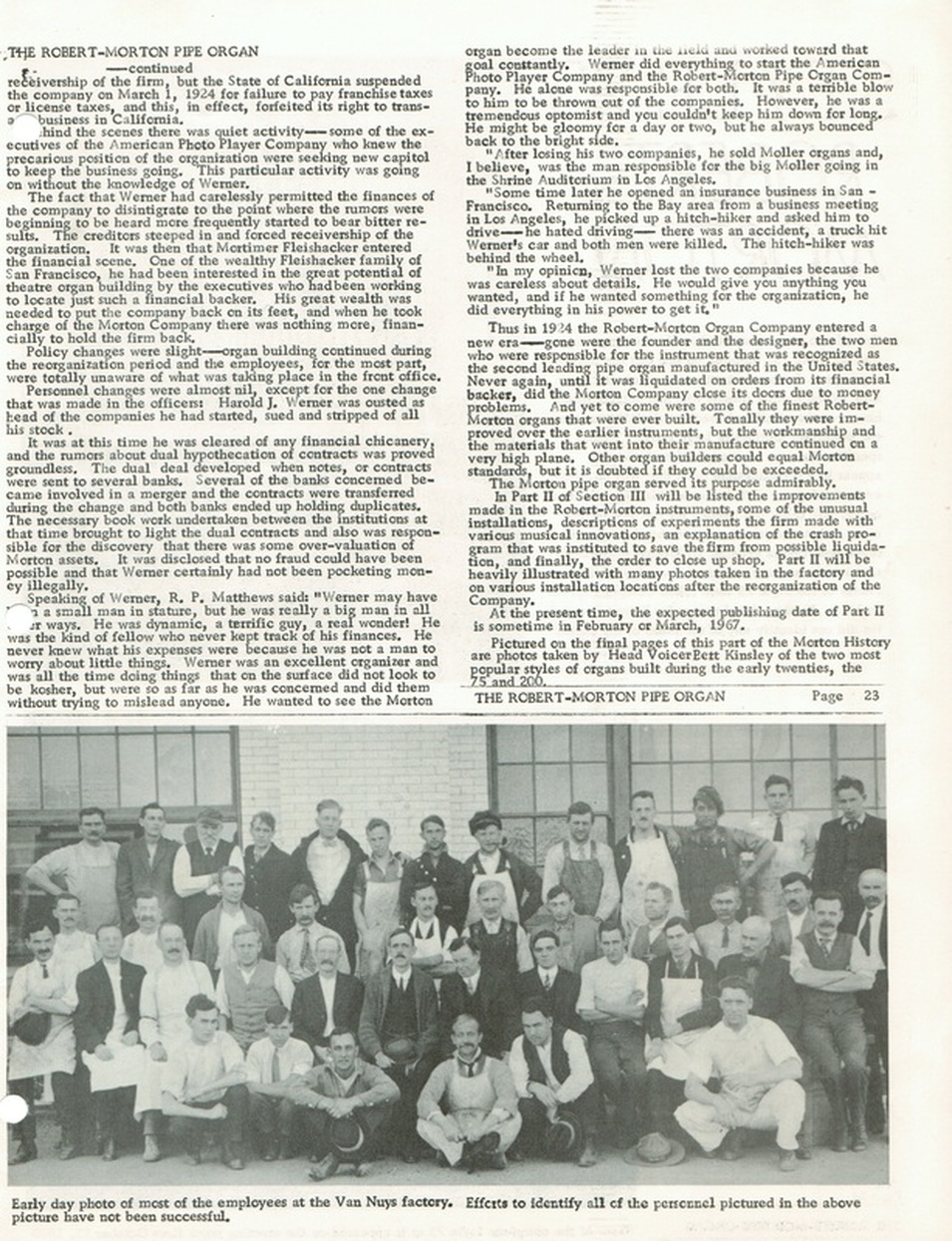

"Early in 1925 The Photo Player Company name was dropped, and the final corporate title became the Robert Morton Organ Company. Schiller remained as general manager and R.P. Matthews was elected vice-president, remaining in his New York office to oversee the national advertising program as well as the eastern, midwestern and southern sales territories. Under Schiller's management an enormous expansion program was undertaken, nearly doubling the size of the factory before the end of 1925. The peak number of employees remains unknown, although a photograph of the firm's work force before the expansion shows nearly 100 persons. Another clue is that, at the height of production (probably in 1926) twenty people were employed just in the machine shop were chest magnets, reed shallots and other metal parts we fabricated". (2 : 500)

The Berkeley factory, no longer the "parent company" plant, was closed in 1925, and Fotoplayer production was moved to Van Nuys, although the executive offices remained in San Francisco. In 1927, Schiller stepped down, having completed his reorganization work, and R.P. Matthews became the general manager of the Robert Morton Organ Company. (2 : 500) Sales were booming, Robert Morton's product was better than ever, and things looked rosy for the future of the firm, as far as the eye could see.

Also in 1927 -- Al Jolson appeared in "The Jazz Singer", and uttered audible words from the silver screen, for the first time,

"You ain't seen nothin yet. . ."

On June 15, 1919, the factory closed for a significant period of time, opening again in October (4 : 21).

But the greatest dispruption came in 1923 / 1924, when the State of California suspended Robert Morton's charter of incorporation on March 19, 1924, (4 : 23) for failure to pay franchise taxes. (4 : 4) This apparently happened because of a sudden dearth of funds which was provoked by a serious charge -- hypothecation of contracts by the firm. The charges were specifically leveled at H.J. Werner, who was accused of "selling organs in the East, obtaining the money for them and then pledging the contracts again in the West to get additional money" (4 : 21) Essentially, an organ would be sold, the money paid to the company, and then the contract for that organ would be taken to a bank and used for collateral on a loan for the value of the contract, which is an act of criminal fraud.

Ultimately, it was determined that Werner had committed no fraud, but had managed the company's finances so carelessly that most of the time it teetered on the brink of insolvency.

Rumors to this effect began to circulate in banking circles, although few at the company were aware of what was going on. Stanley Williams was made aware of the problems by R.P. Elliott, who persuaded him to come work for the Kimball Organ Company. Williams submitted his resignation in 1923, less than a year before the meltdown. Robert Morton's stockholders and creditors, however, also become aware and this produced a stockholder lawsuit against Robert Morton and H.J. Werner. This forced the company into receivership in mid-1923, and ultimately resulted in the complete reorganization of the company, which became The Photo Player Company. This blanket name applied to both the American Photo Player Company and the Robert Morton Organ Company, although organs continued to be produced bearing the Robert Morton nameplate. In fact, most of the company's employees didn't notice much of a difference during this stormy period for management of the company. (

Werner was removed from the company, and replaced by James A.G. Schiller, who was appointed as general manager. Schiller was no organ man, but was a good businessman and organizer, and in a short period of time he made changes in the organization that even the employees on the factory floor could see and appreciate. As noted by Paul Carlsted, Schiller "turned the plant upside down [and] surprisingly enough he got everything organized on a plan and it went along much better" (2 : 500) Casting about for backers, the company found the ideal financial support from San Francisco banker and businessman, Mortimer Fleischacker, president of the Anglo-California Trust Company in that city. 2 : 500, 4 : 23) From this point onward, Robert Morton had no more financial problems.

"Early in 1925 The Photo Player Company name was dropped, and the final corporate title became the Robert Morton Organ Company. Schiller remained as general manager and R.P. Matthews was elected vice-president, remaining in his New York office to oversee the national advertising program as well as the eastern, midwestern and southern sales territories. Under Schiller's management an enormous expansion program was undertaken, nearly doubling the size of the factory before the end of 1925. The peak number of employees remains unknown, although a photograph of the firm's work force before the expansion shows nearly 100 persons. Another clue is that, at the height of production (probably in 1926) twenty people were employed just in the machine shop were chest magnets, reed shallots and other metal parts we fabricated". (2 : 500)

The Berkeley factory, no longer the "parent company" plant, was closed in 1925, and Fotoplayer production was moved to Van Nuys, although the executive offices remained in San Francisco. In 1927, Schiller stepped down, having completed his reorganization work, and R.P. Matthews became the general manager of the Robert Morton Organ Company. (2 : 500) Sales were booming, Robert Morton's product was better than ever, and things looked rosy for the future of the firm, as far as the eye could see.

Also in 1927 -- Al Jolson appeared in "The Jazz Singer", and uttered audible words from the silver screen, for the first time,

"You ain't seen nothin yet. . ."

the best of times, the worst of times

If 1925 ushered in a new era of stability, prosperity and quality for the Robert Morton firm, 1927 was a portent of certain doom, although few saw it coming.

Mary Charles, the wife of super-salesman Henry "Cocky" Charles recounts her first experience with "talkies":

"One day he had me go downtown to the Tower Theatre [Los Angeles; ed] to hear Vitaphone, and then asked me what I thought of it. . .I said frankly that for news it was good, but I didn't think it would take away silent film drama. I was certainly wrong." (4 : 10) But although he stayed with the firm until it closed its doors, "Cocky" had certainly seen the writing on the wall.

////MORE TO COME. . .

Mary Charles, the wife of super-salesman Henry "Cocky" Charles recounts her first experience with "talkies":

"One day he had me go downtown to the Tower Theatre [Los Angeles; ed] to hear Vitaphone, and then asked me what I thought of it. . .I said frankly that for news it was good, but I didn't think it would take away silent film drama. I was certainly wrong." (4 : 10) But although he stayed with the firm until it closed its doors, "Cocky" had certainly seen the writing on the wall.

////MORE TO COME. . .

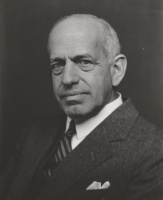

Builder's Plates

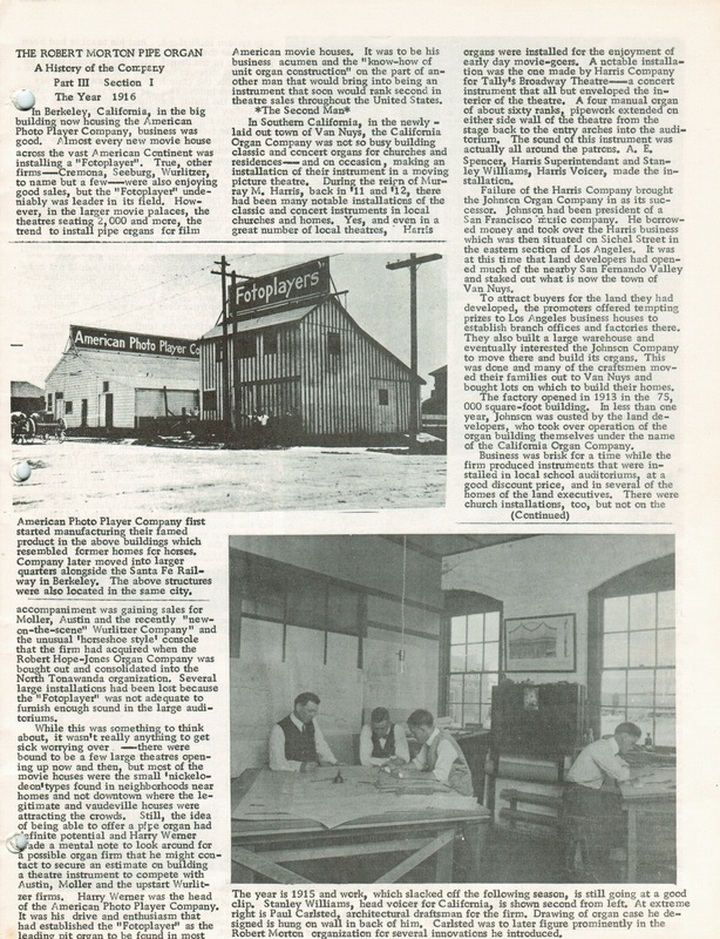

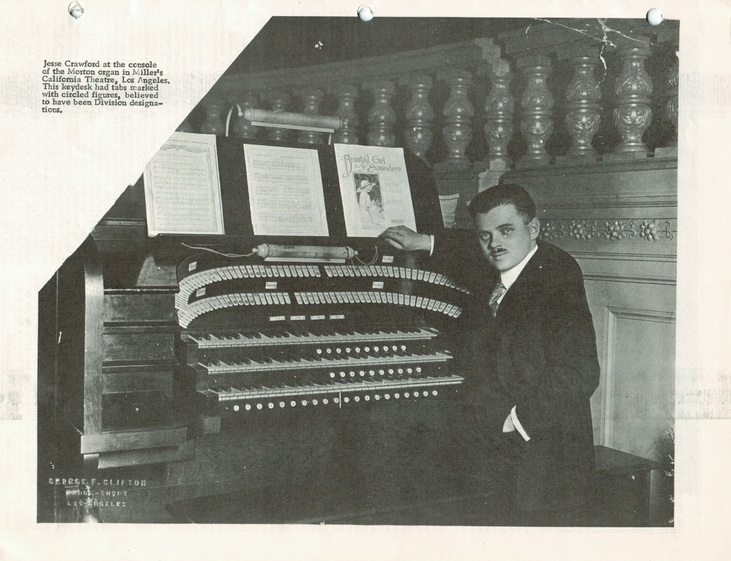

PHOTO VII

The "organ pipe" builder's plates were used very early on by the company. The console of the 1917 St. Francis organ in San Francisco bore a plate like this. These plates were made of thin brass, and interestingly indicated factory locations in both Van Nuys, California, and Highland, Illinois. It is also noted that Robert Morton is a "Division of the American Photo Player Co.", with offices in New York, Chicago and San Francisco. The San Francisco office is likely the Berkeley headquarters of the Photo Player firm.

It appears that before the Robert Morton Organ Company actually came into being, The American Photo Player Company had established a relationship with the Wicks Organ Company in Highland, Illinois. The mysterious "Beethoven" organ was likely an attempt to enter the theatre organ market through Wicks, but the association proved beneficial in other ways. Frequently, when orders overwhelmed factory production, or when the factory was closed (during economic crises), or when the geography made it a preferred choice, Robert Morton organs were built in Highland, rather than Van Nuys. All of these instruments bore the pictured nameplate, listing both factory locations. The Highland reference appears on no other Robert Morton builder's plate which the author has seen (excepting the aformentioned "Beethoven" plate). This connection is discussed in greater detail in the Production section.

By David Junchen's tally, 37 of these Wicks-Mortons were built (1:86), but there may have been more. Construction of the instruments reflected Wicks' use of the Direct-Electric (TM) action they had patented, and smaller instruments did not have the relays contained in their consoles, as was standard Robert Morton practice. It is worth noting that the standard Robert Morton relay was far smaller than a standard Wicks relay for the same-sized organ, because when installed in the console, the relay system required no key relay; the key contacts fulfilled that function.

The specifications bore definite resemblance to Robert Morton standard specifications, but other details, such as stop engraving, console design, and pipework design were usually in conformity with Wicks practice. Interestingly, the author has observed that a Wicks-built Robert Morton had stops with Wicks' very small engraving, but that the division plates were obviously made at the Van Nuys facility, and bore Robert Morton's engraving fonts. The Van Nuys plant would apparently send along some items to be included with the organ, usually console parts, although other items may also have been provided. Whether this was to make the organ more "Mortonesque" or whether these were simply parts that had already been picked before the site of construction was determined is not known.

It appears that most of the Robert Morton organs built in Highland were smaller, two manual instruments.

It appears that before the Robert Morton Organ Company actually came into being, The American Photo Player Company had established a relationship with the Wicks Organ Company in Highland, Illinois. The mysterious "Beethoven" organ was likely an attempt to enter the theatre organ market through Wicks, but the association proved beneficial in other ways. Frequently, when orders overwhelmed factory production, or when the factory was closed (during economic crises), or when the geography made it a preferred choice, Robert Morton organs were built in Highland, rather than Van Nuys. All of these instruments bore the pictured nameplate, listing both factory locations. The Highland reference appears on no other Robert Morton builder's plate which the author has seen (excepting the aformentioned "Beethoven" plate). This connection is discussed in greater detail in the Production section.

By David Junchen's tally, 37 of these Wicks-Mortons were built (1:86), but there may have been more. Construction of the instruments reflected Wicks' use of the Direct-Electric (TM) action they had patented, and smaller instruments did not have the relays contained in their consoles, as was standard Robert Morton practice. It is worth noting that the standard Robert Morton relay was far smaller than a standard Wicks relay for the same-sized organ, because when installed in the console, the relay system required no key relay; the key contacts fulfilled that function.

The specifications bore definite resemblance to Robert Morton standard specifications, but other details, such as stop engraving, console design, and pipework design were usually in conformity with Wicks practice. Interestingly, the author has observed that a Wicks-built Robert Morton had stops with Wicks' very small engraving, but that the division plates were obviously made at the Van Nuys facility, and bore Robert Morton's engraving fonts. The Van Nuys plant would apparently send along some items to be included with the organ, usually console parts, although other items may also have been provided. Whether this was to make the organ more "Mortonesque" or whether these were simply parts that had already been picked before the site of construction was determined is not known.

It appears that most of the Robert Morton organs built in Highland were smaller, two manual instruments.

Opus Plates

PHOTO VIII

- Opus plate from Model 18,

number 2274 )

Smaller instruments (including Fotoplayers) frequently bore plates similar to this one, lieu of the larger decorative plates. The stamped plates included the opus number and model of the instrument and, although they were sometimes found on consoles, they frequently appeared on chest bearers in the chambers. To the extent that those bearers were lost, or stripped of their hardware over time, the opus number of the instruments were lost. In many Robert Morton consoles, there are sometimes references to the venue in which the organ was installed, usually in the form of chalked or grease-penned notations found on the insides of the backs of the consoles, or on the inside of the heel plate of the pedalboard. The 2/5 instrument which found its way to the Metropolitan Theatre in Hermosa Beach, California, bore the name "Pacific Coast" on the inside of its back, apparently a reference to the holding company which financed the theatre (the theatre wasn't actually named until after it was built).

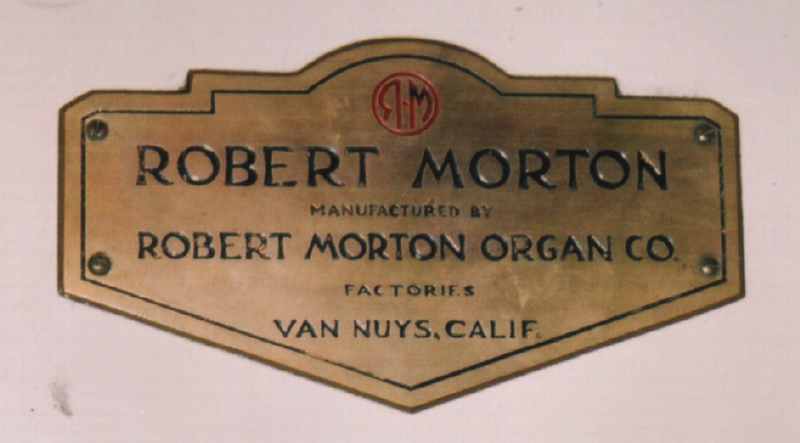

The Robert Morton "Shield" Plate

In 1923, the company began to use the large, brass shield-shaped nameplate on all of its instruments, usually mounted on the fallboard of the console, sometimes with a plate on each side. The two-toned version (with the R-M logo in red) is believed to be a later version of the plate.

- SOURCE MATERIAL -

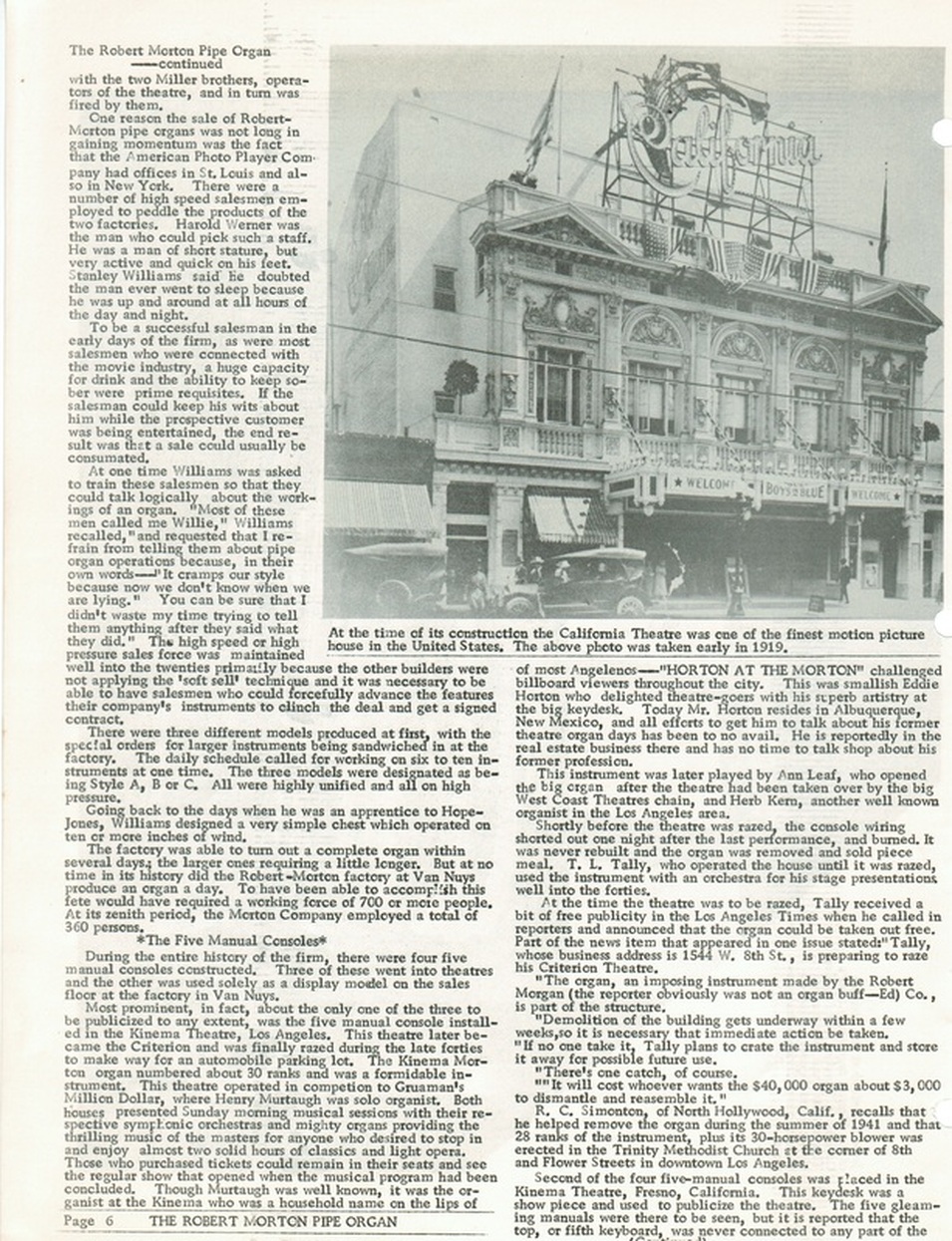

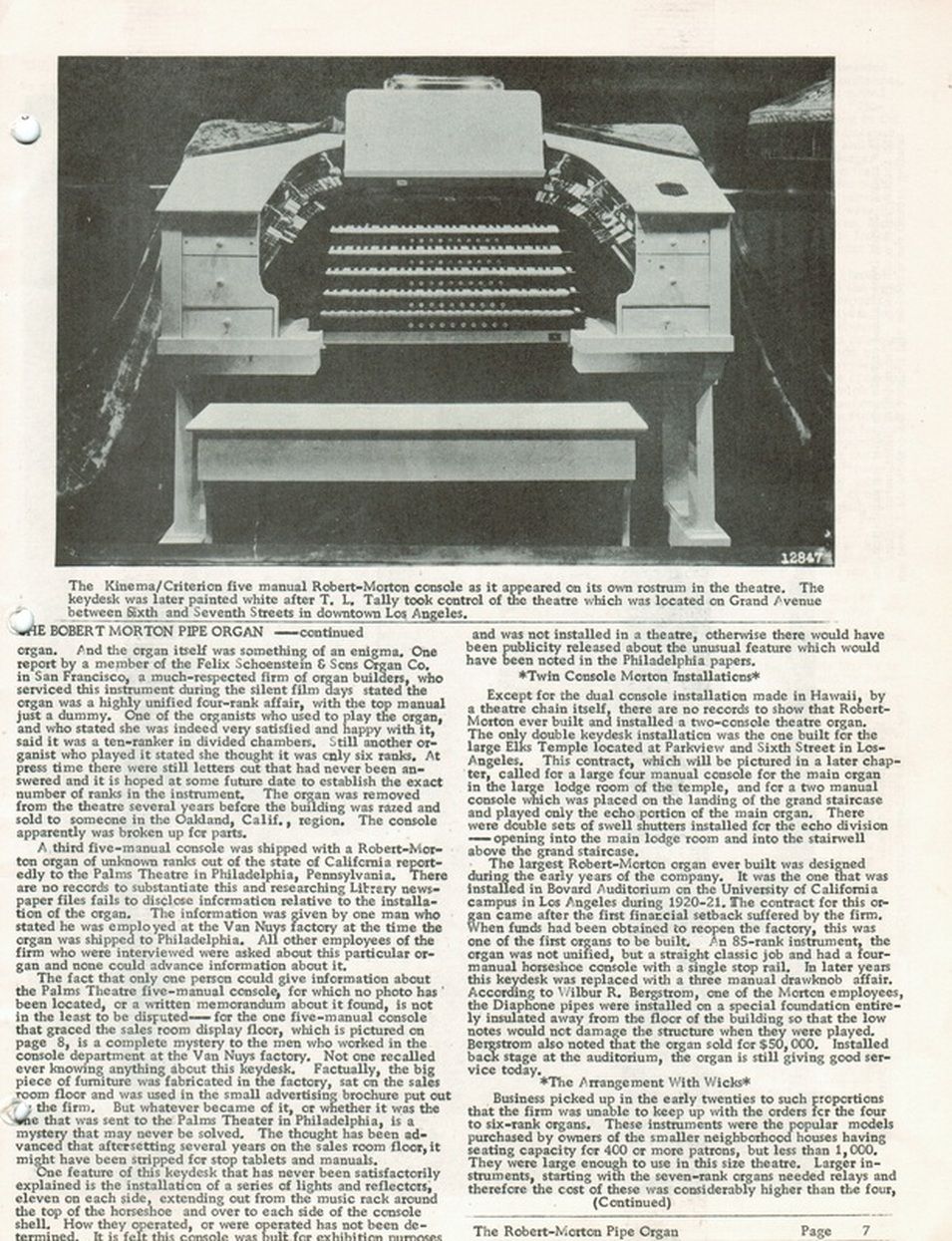

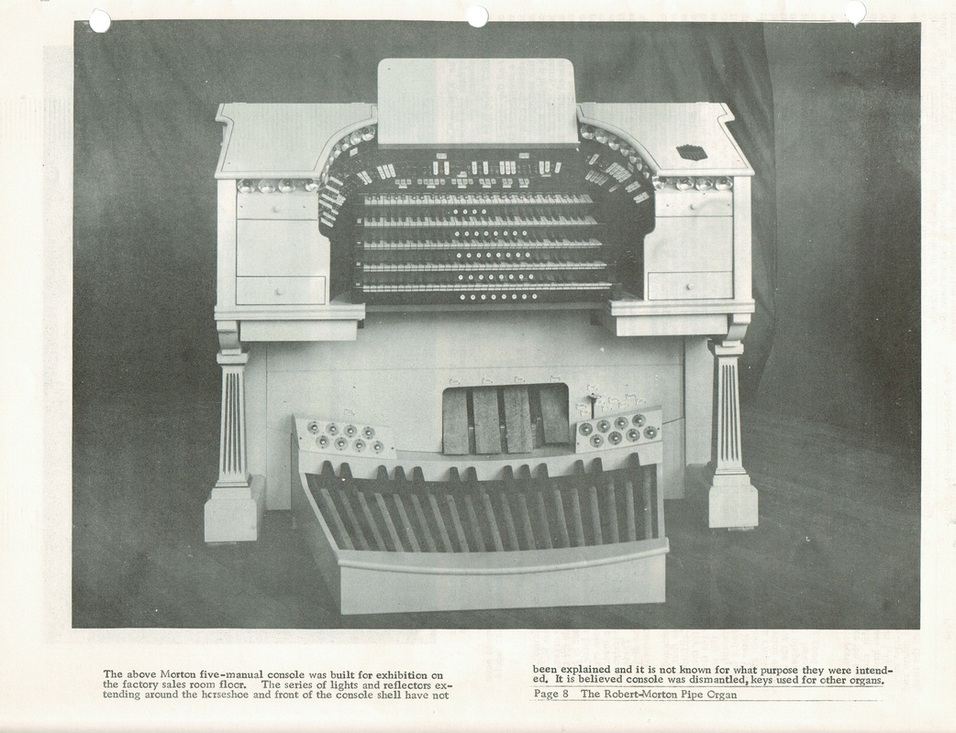

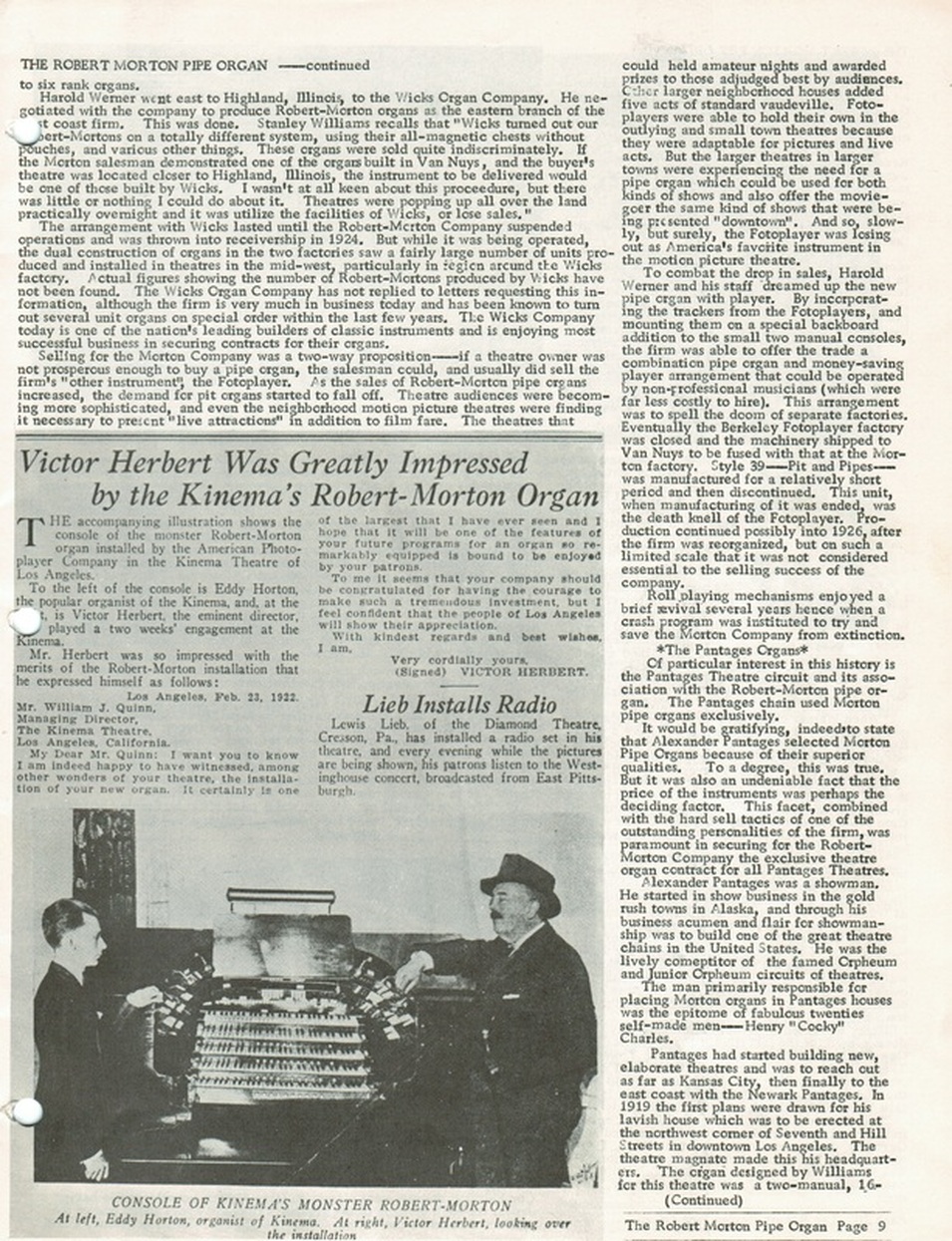

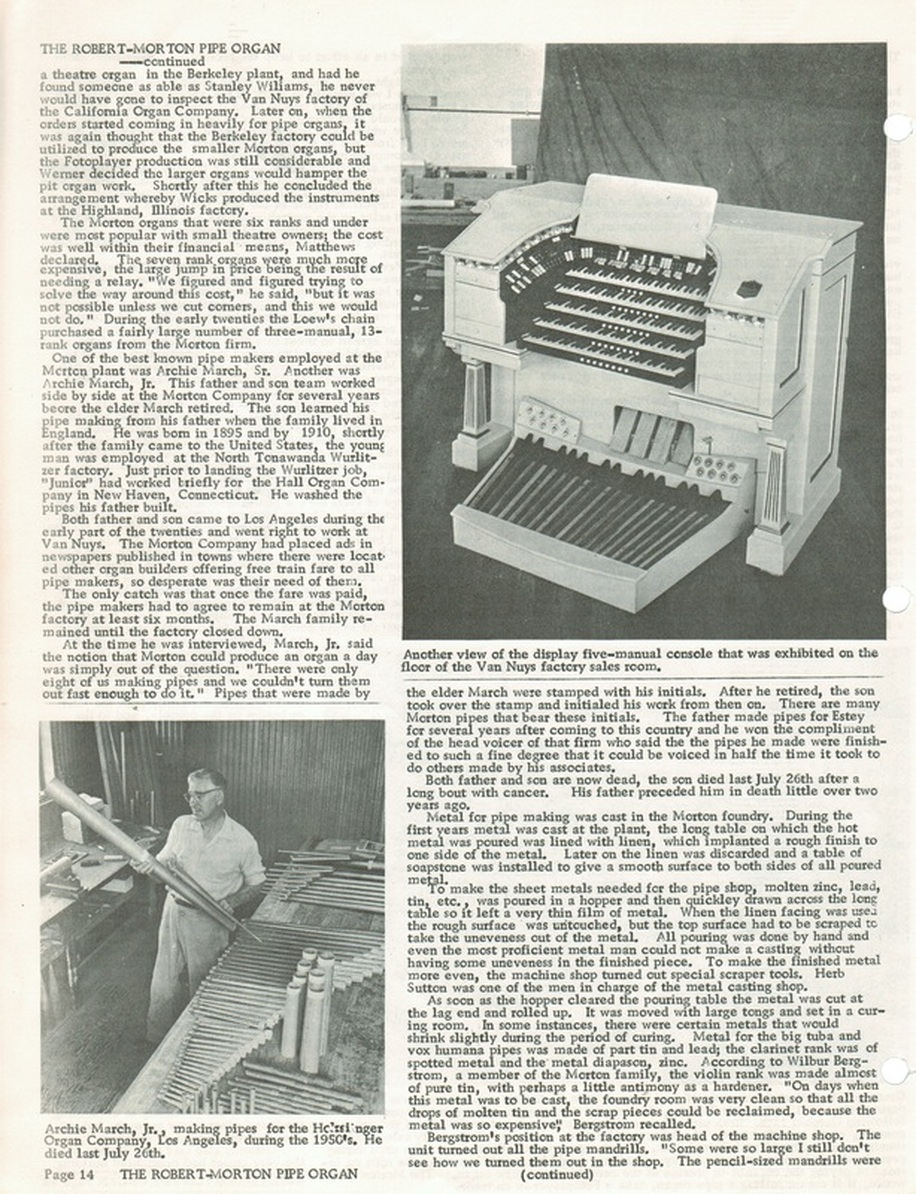

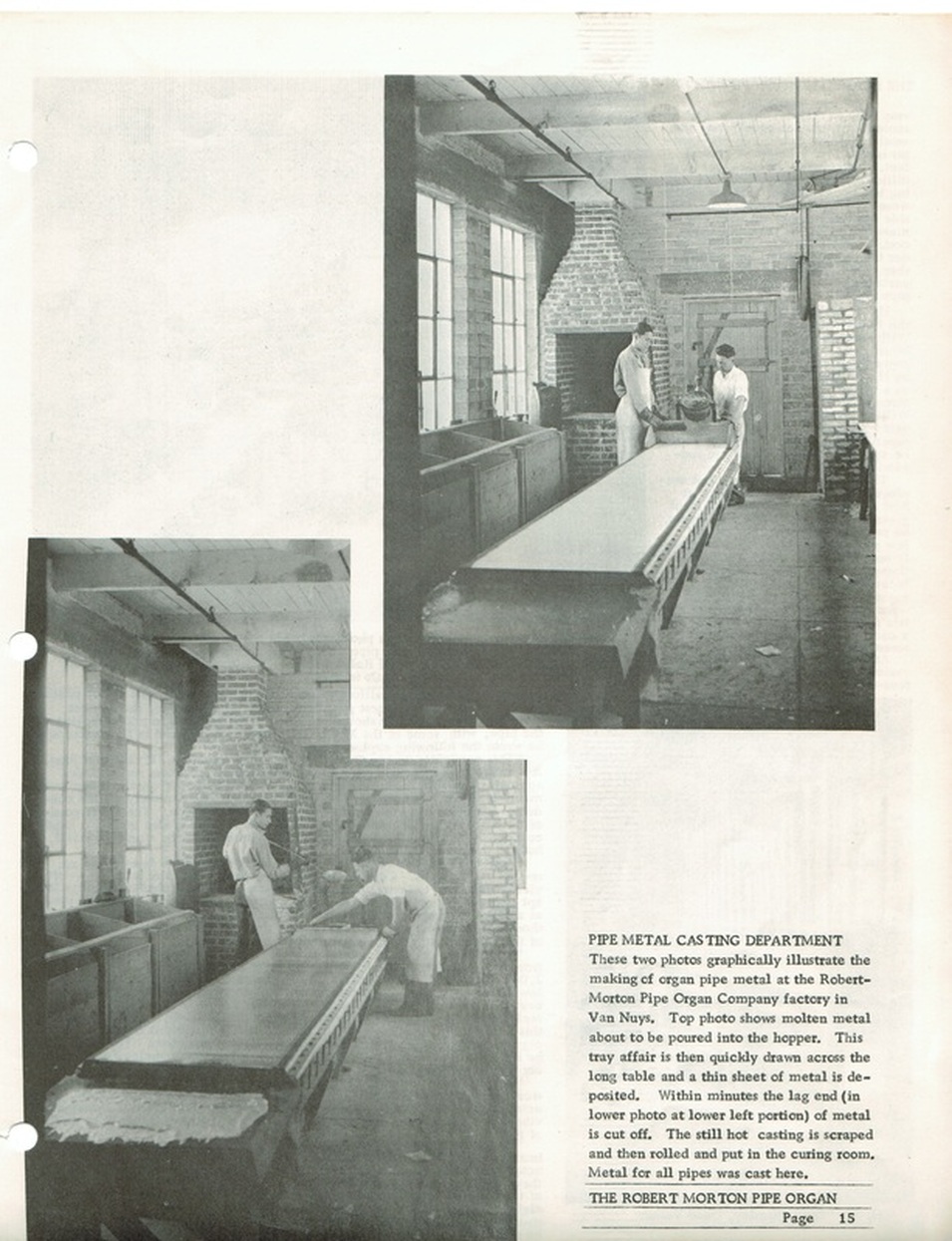

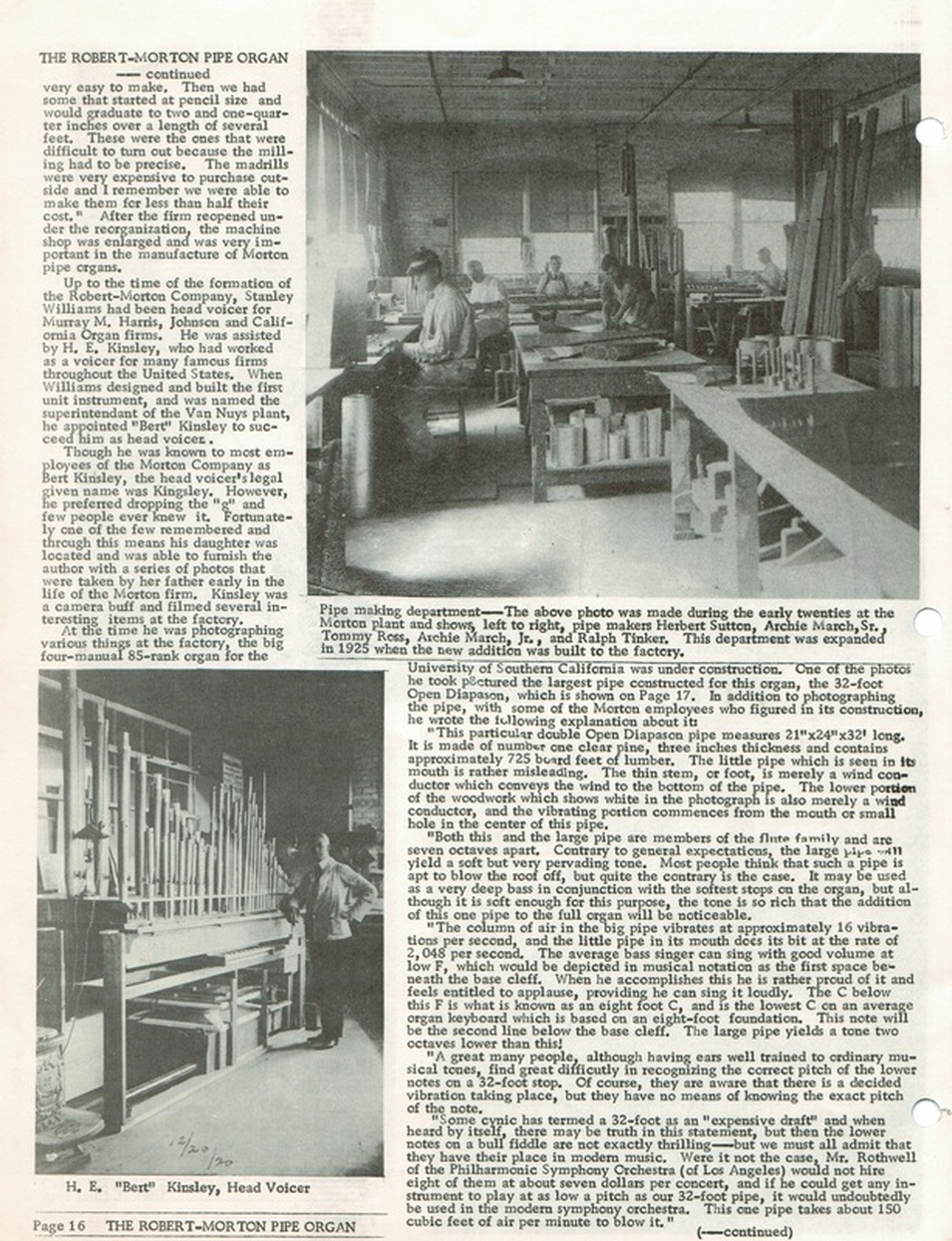

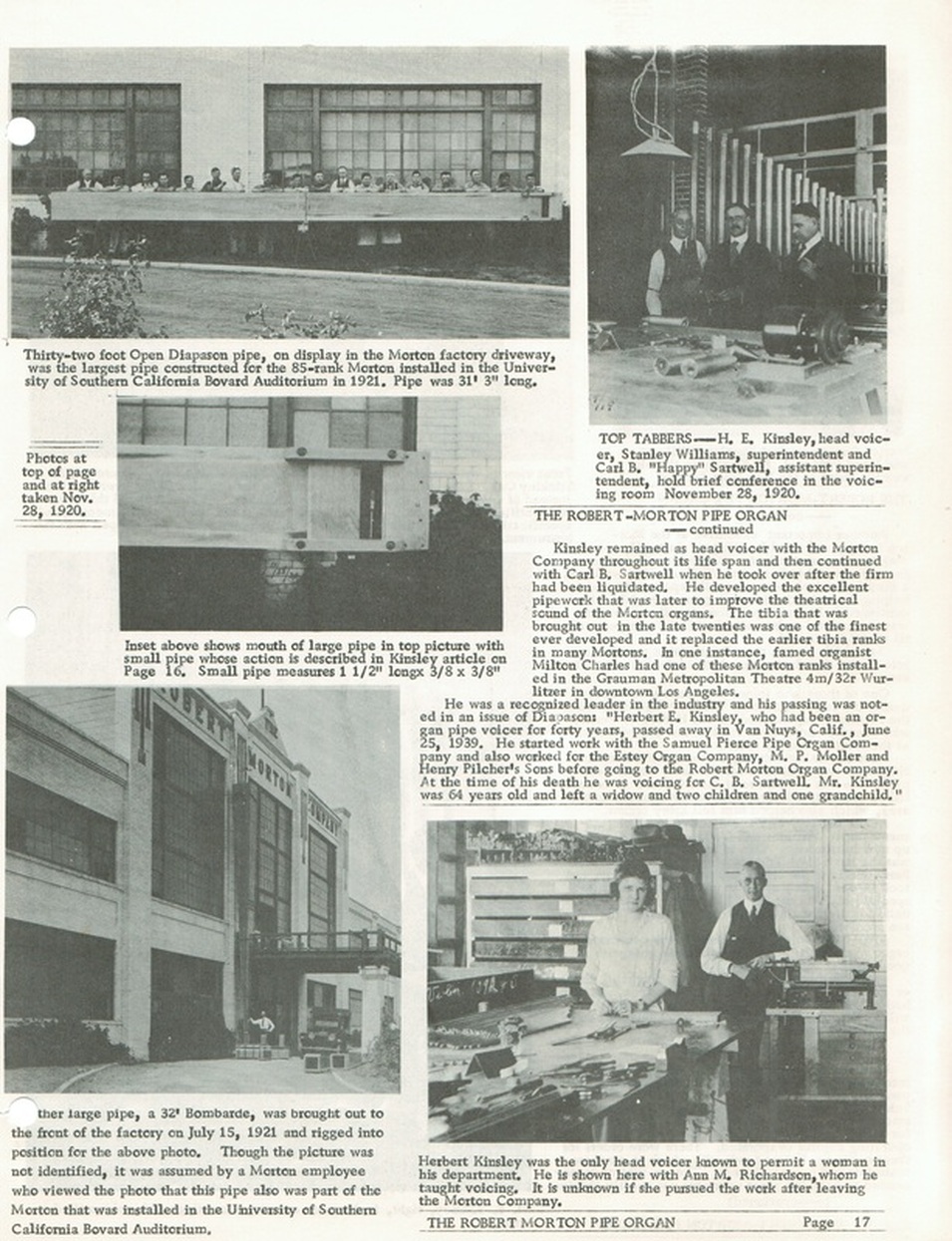

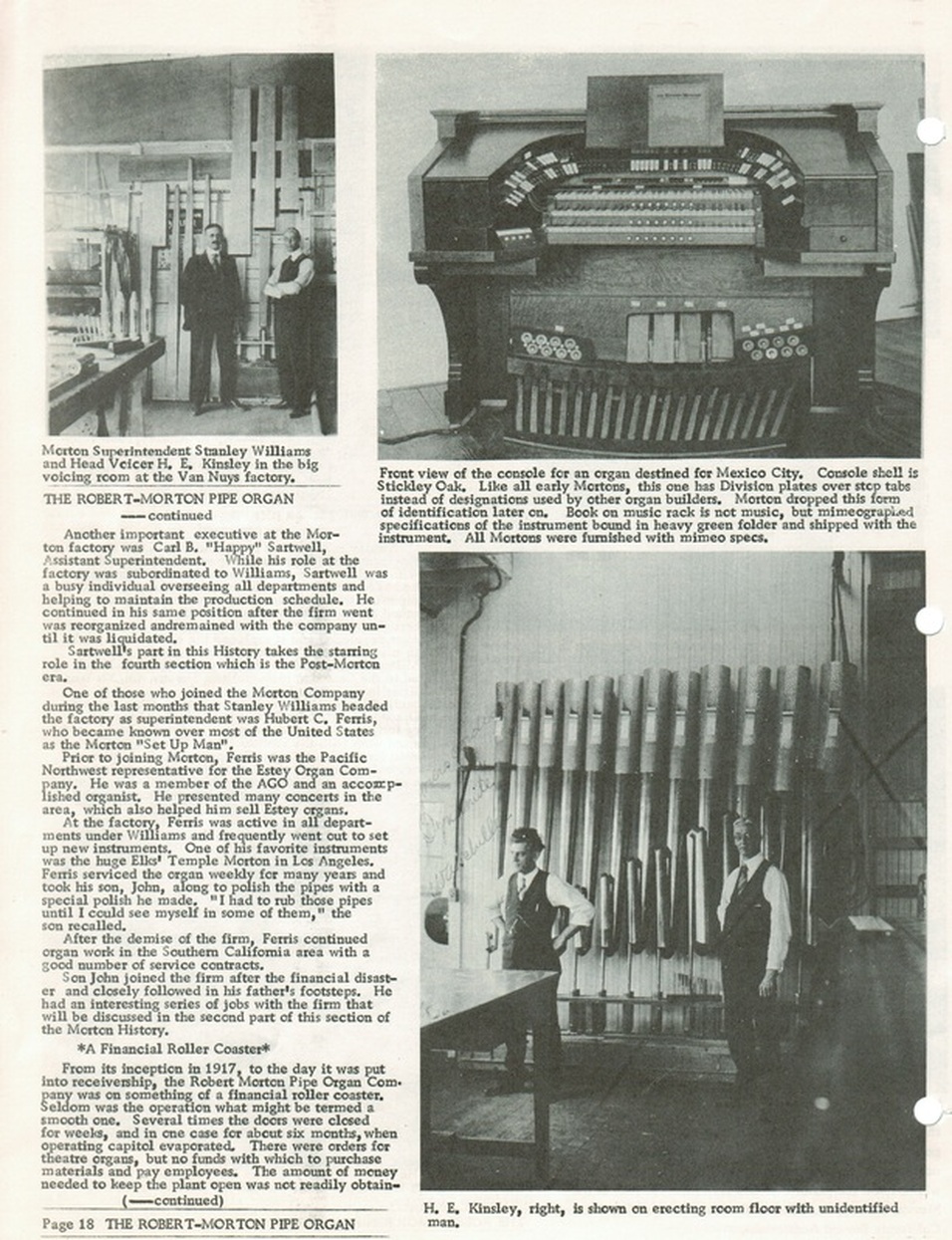

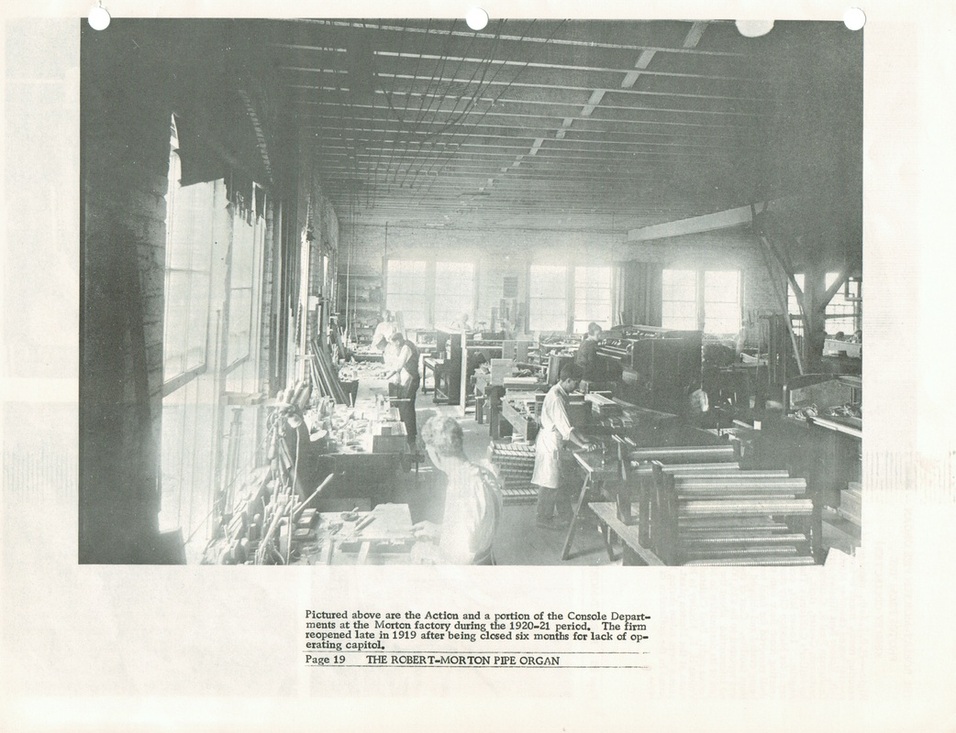

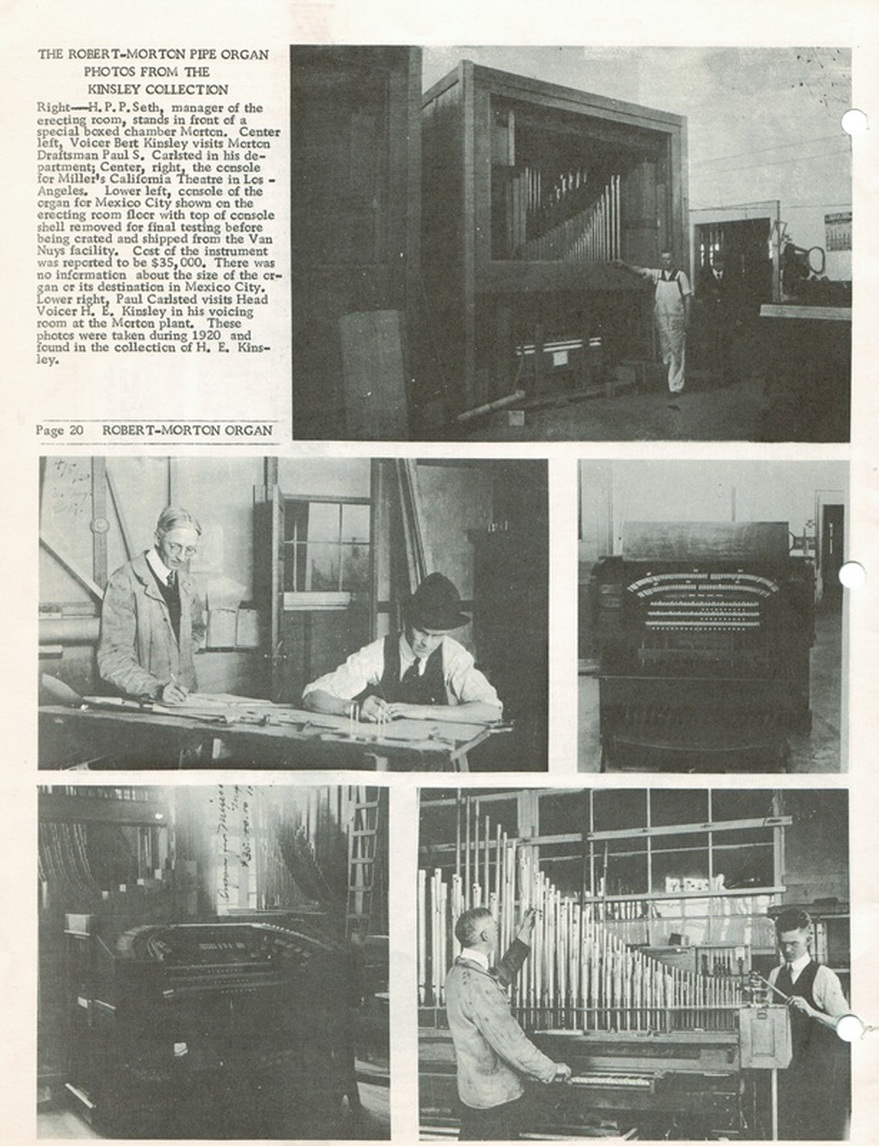

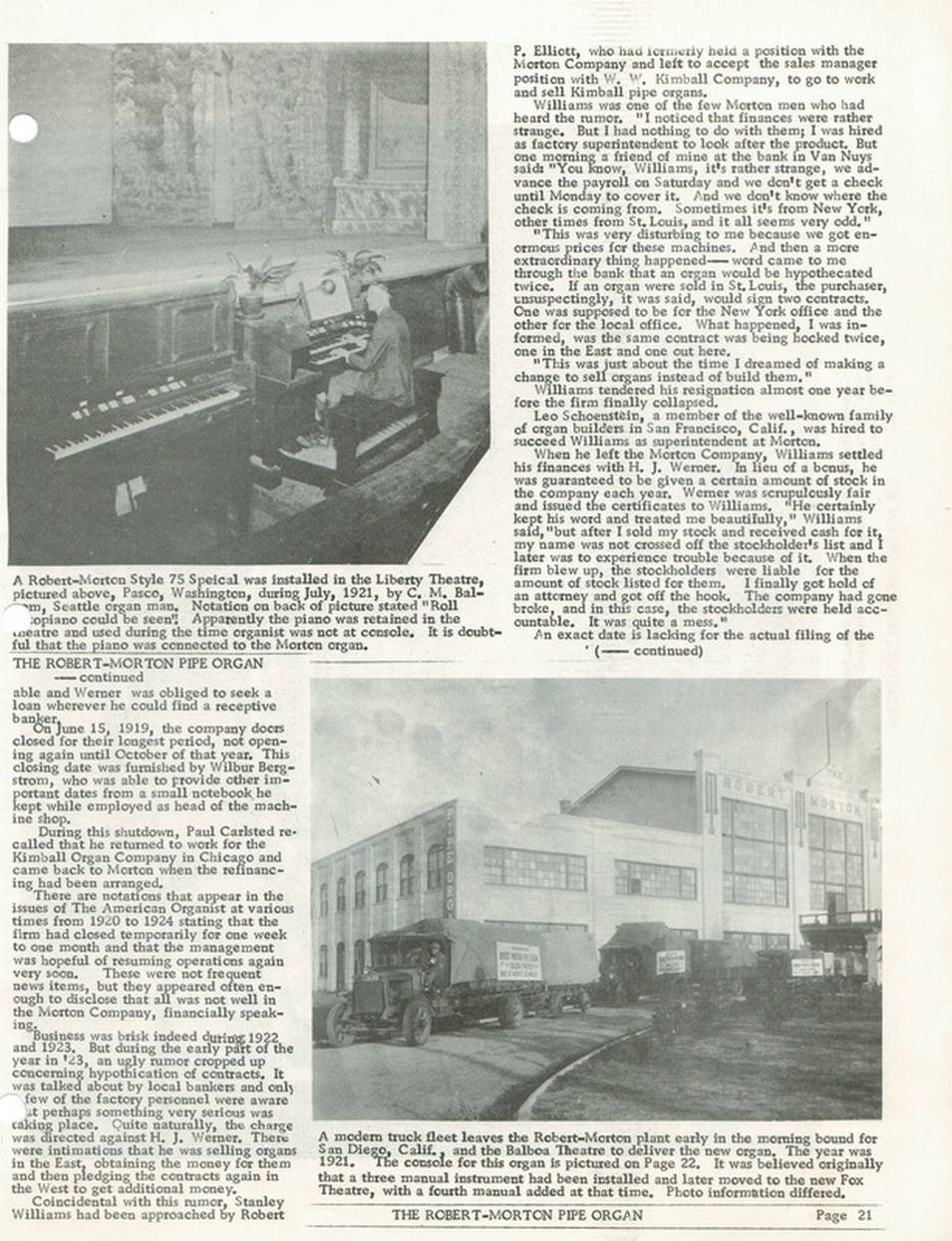

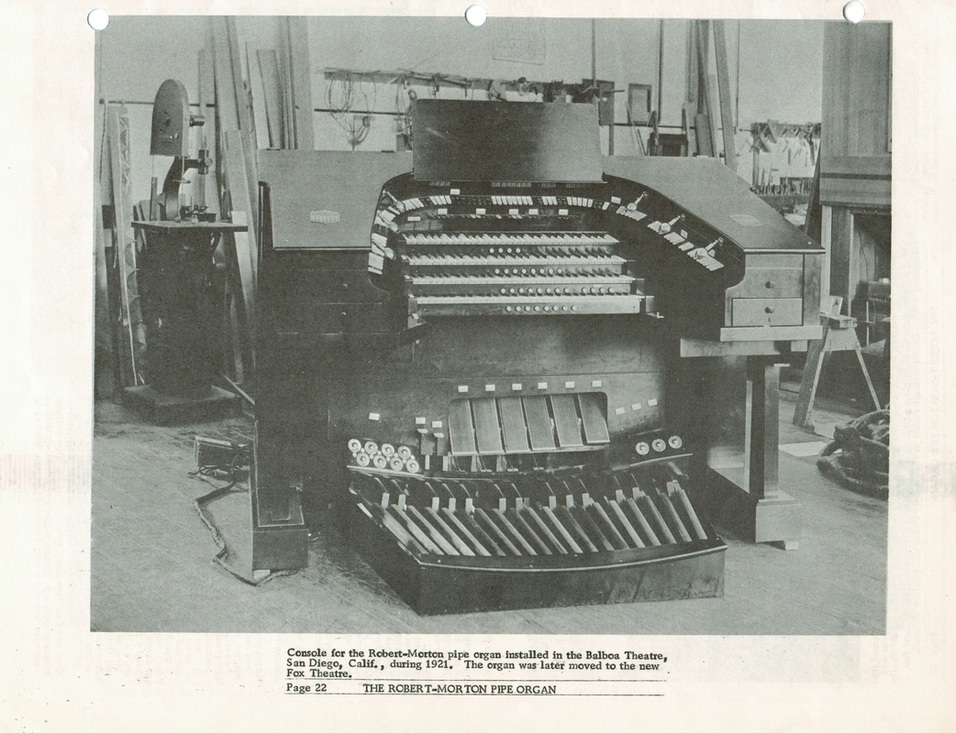

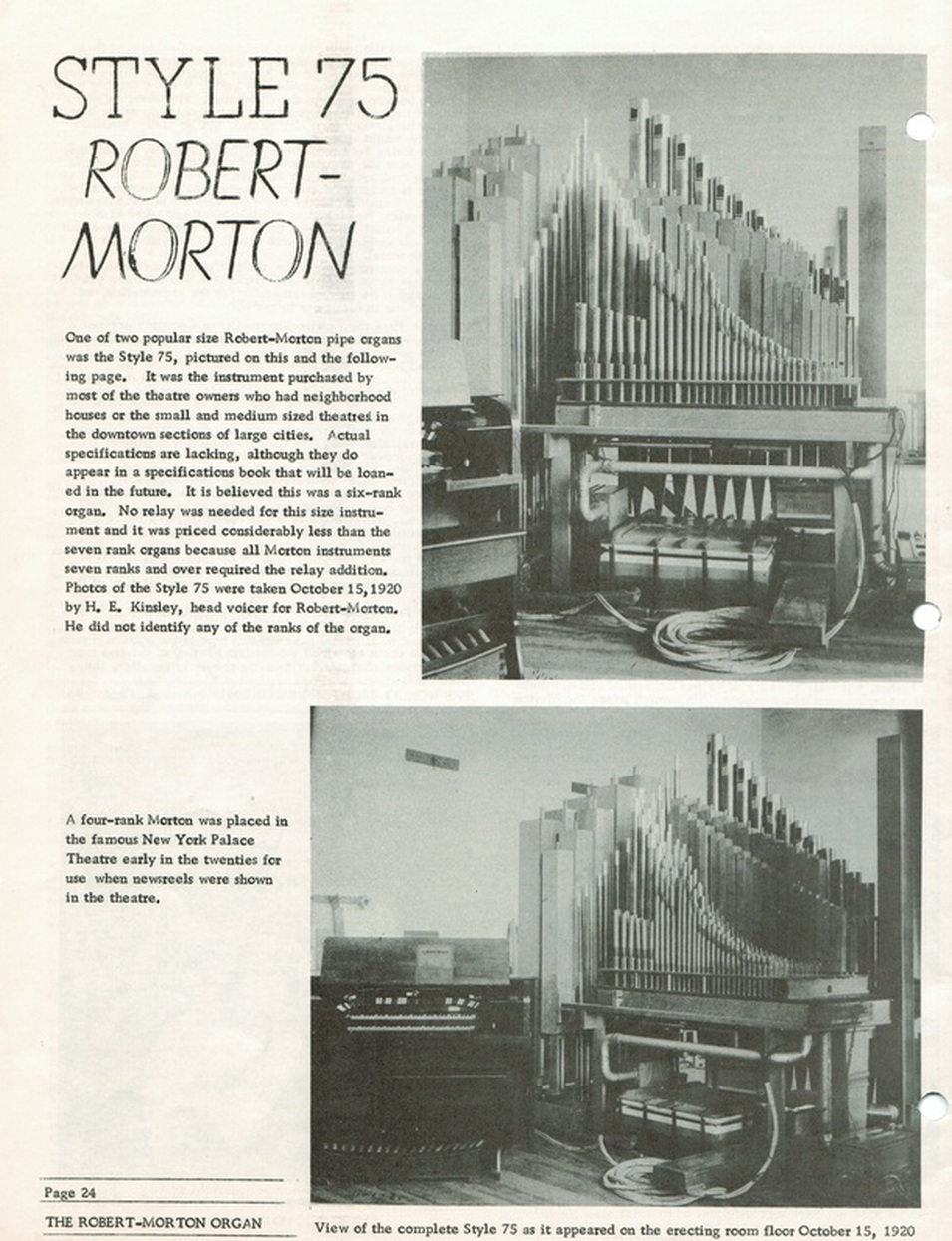

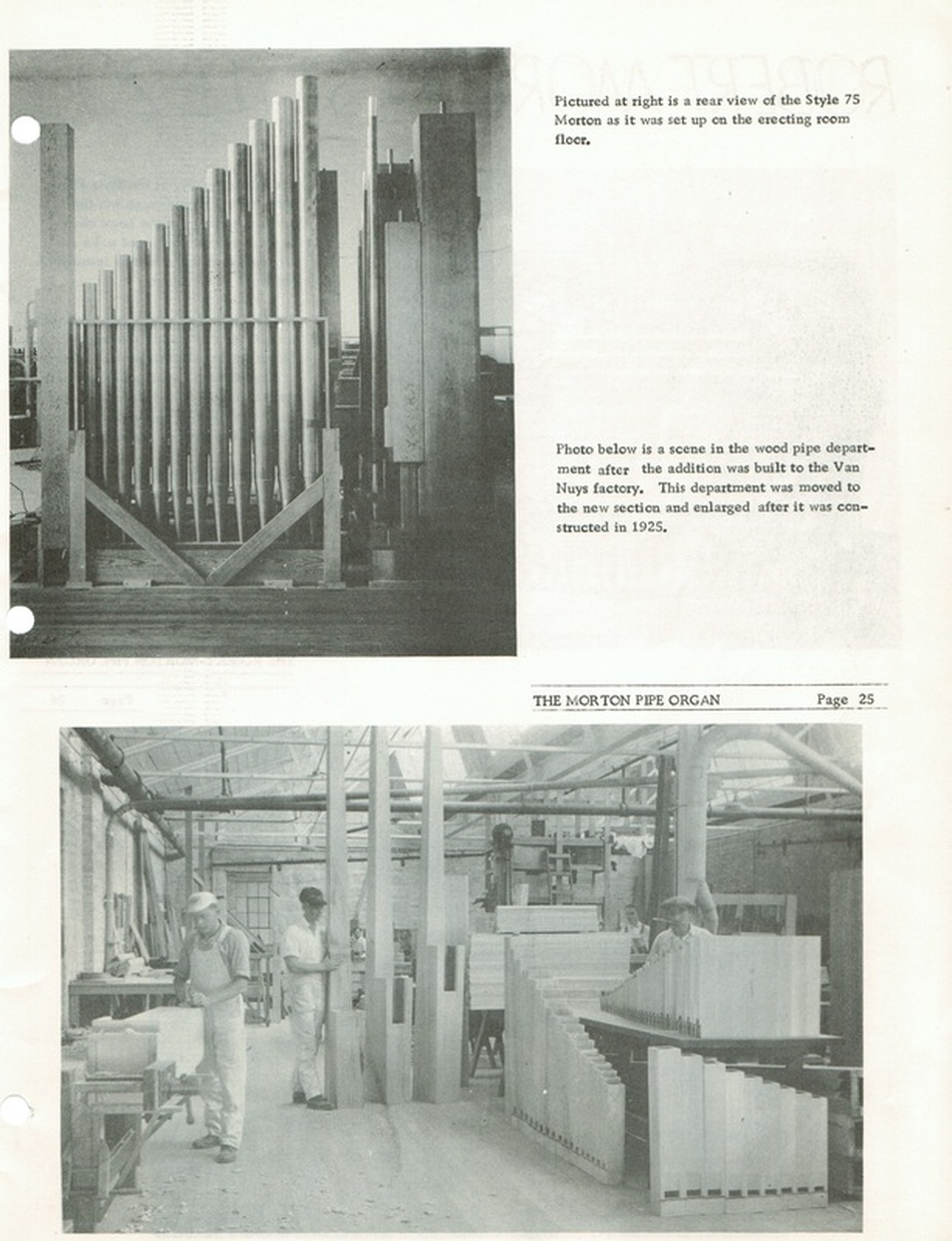

The Console Magazine History of Robert Morton, part III

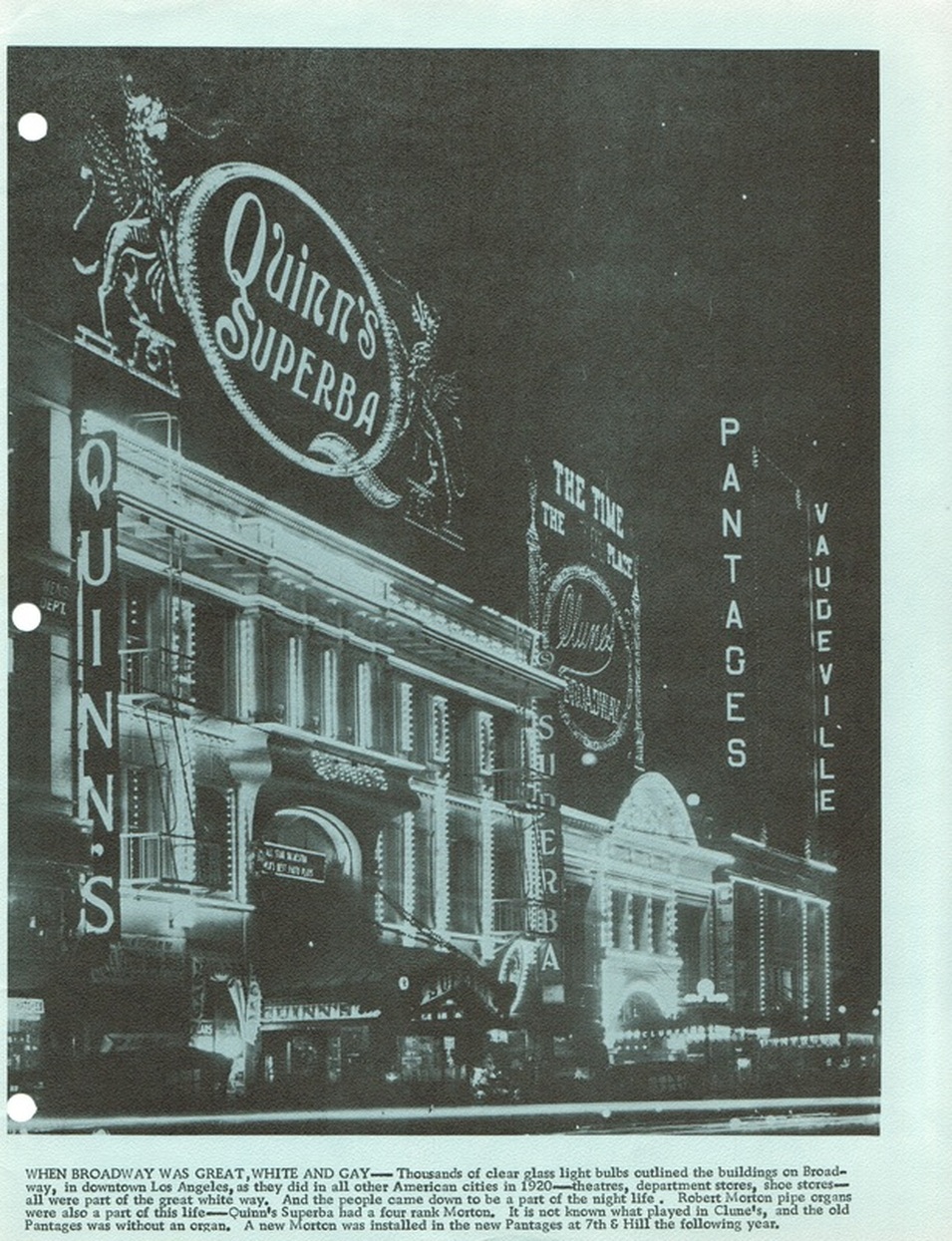

The following is a scan of the History of the Robert Morton Unit Organ, Section III, published by The Console Magazine (edited and published by Tom B'Hend) which appeared with the September, 1966 issue of the magazine. Although it contains some factual errors (as does this website, I'm sure), it is one of the most complete attempts at presenting a comprehensive history of the company, and has been used a major resource about the company by David Junchen in his excellent Encyclopedia of the Theatre Organ, and by others. Because this site is a resource for such information, and because there is so much detail in this original work, I prefer to publish it in its entirety, rather than to attempt to summarize it.