CONSTRUCTION PROTOCOLS

CONSOLE DESIGN

Robert Morton organ consoles have frequently been referred to as "industrial" looking, with earlier "stile" types of consoles sometimes being compared to the Arts & Crafts movement work of Gustav Stickley. In fact, the early Robert Morton consoles, from 1917 until about 1922 or 1923, were an outgrowth of previous construction concepts embraced by the California Organ Company and Murray M. Harris Organ Company. (the pictured console is in Redeemer Lutheran Church, Los Angeles, California; a 1923 church instrument of 15 ranks).

Favoring oak and other "churchly" hardwoods, the first Robert Morton consoles were perhaps homely, compared to Wurltizer's elegant consoles. Although Robert Morton was not reluctant to depart from the tried and true in designing their consoles, there are certain formats which re-occur often enough to be considered "default console designs". Below I have designated a few of the distinguishable styles of console design; bearing in mind that just when you think you've nailed down the Robert Morton design ethic, something new pops up. I've arbitrarily called these particular design bases "rolltop", "stile", "panel", "carlsted", and "dreadnought".. To these categories we must obviously add the unique Wonder Morton consoles, whose designs were a major departure from other Robert Morton console work.

Favoring oak and other "churchly" hardwoods, the first Robert Morton consoles were perhaps homely, compared to Wurltizer's elegant consoles. Although Robert Morton was not reluctant to depart from the tried and true in designing their consoles, there are certain formats which re-occur often enough to be considered "default console designs". Below I have designated a few of the distinguishable styles of console design; bearing in mind that just when you think you've nailed down the Robert Morton design ethic, something new pops up. I've arbitrarily called these particular design bases "rolltop", "stile", "panel", "carlsted", and "dreadnought".. To these categories we must obviously add the unique Wonder Morton consoles, whose designs were a major departure from other Robert Morton console work.

THE ROLLTOP CONSOLE -- Most of the Robert Morton theatre organ consoles sporting rolltops are of very early origin. It's clear that the rolltop was considered a useful "layover to catch meddlers" in the case of organ consoles which within public access in churches and theatres. Robert Morton church organs frequently had rolltops, although not always. As the concept of the theatre organ "as its own creature" developed, and separated from the concept of the church organ, the roll top was dropped for theatre organ installations. The four manual Bovard Auditorium organ, which had a "horseshoe" stoprail, also had a roll top which covered up keyboards and stops when the organ was not being used. (the example pictured was the 2/16 organ in the Pantages theatre in Salt Lake City, Utah).

THE "STILE" CONSOLE -- Essentially, this particular design of console gets its name from the posts (aka stiles) under each side of the keydesk, which are intended to provide support for the overhang of the keyboards and stoprail. The stiles did tend to give the consoles more of an Arts & Crafts look to them, although it is not clear if this was intended by the designer or just a lucky happenstance. These earlier theatre "stile" consoles frequently included a roll top, and a fairly low profile, particularly in the two manual models.

Few, if any, California Organ Company consoles survive intact or at all. The few examples seen by the author tend to support the idea that the "stile" console is a continuation of California Organ Company console design.

Few, if any, California Organ Company consoles survive intact or at all. The few examples seen by the author tend to support the idea that the "stile" console is a continuation of California Organ Company console design.

THE "PANEL" CONSOLE -- An equally ubiquitous style of Robert Morton console could be called the "Panel" console, in the same sense that Wurlitzer also had a panel console. Instead of the supporting styles, the sides used a construction of square panels, extending out towards the front of the keydesk, frequently with a small, decorative corbel. This console style, along with the "stile" console, was the primary style of non-custom construction and design used in early Robert Morton consoles, right up to the company reorganization in 1925.

Although panel consoles tended to be staid, dignified affairs, one of the more ornamented panel consoles can be seen on the Elks 99 4-manual organ in Los Angeles, California (see Gallery)

Although panel consoles tended to be staid, dignified affairs, one of the more ornamented panel consoles can be seen on the Elks 99 4-manual organ in Los Angeles, California (see Gallery)

THE "CARLSTED" CONSOLE -- Shortly after becoming the head draughtsman for Robert Morton, Paul Carlsted designed a rather more sophisticated console for the company's theatre organs, which was rather more elegant than its "stiled" siblings. These consoles did away with the stiles completely by extending the sides of the console forward a bit to provide support under the front of the keydesk, and incoporated ornamental corbels under the keydesk, similar to the styles used by Wurlitzer, Page and Kimball on some of their instruments. By 1925, both two and three manual consoles were generally built using the Carlsted designs. Three manual consoles would often have "cutout" sections in the center of the upper row of stops to allow the music rack to be placed at a more comfortable height for the organist. (The pictured organ is in the Ohio Theatre, Columbus, Ohio, console as originally configured).

THE "DREADNOUGHT" CONSOLE -- The "dreadnought" class of British battleships described the modern (for the early 20th Century) ironclad, heavily-armored ships, bristling with large-bore gun turrets and other weaponry. Robert Morton's "dreadnought" consoles probably also received the nickname because of their formidable appearance and unique features. These consoles projected power! This particular style seems to have been reserved for four manual consoles. The inclusion of the setter-drawers under the keydesk adds to the visual "weight". Interestingly, the dreadnought consoles did not usually feature the music rack cutouts provided with the three-manual Carlsted designs. Many of these consoles made use of not only the standard automobile style stoprail lighting, but also of unique lensed spotlights located under the stops on the ratguards. These trained ambient light upon most of the stops, filling in those parts of the stoprails missed by the smaller automotive lights.

The pictured console is probably the most "dreadful" of the dreadnoughts -- the spectacular console of the former San Francisco Orpheum organ (which, by the way, is presently in storage and looking for a home -- see "Marketplace").

The pictured console is probably the most "dreadful" of the dreadnoughts -- the spectacular console of the former San Francisco Orpheum organ (which, by the way, is presently in storage and looking for a home -- see "Marketplace").

THE "WONDER" CONSOLE -- The unique positioning of the five Wonder Mortons, all similar, and all in Loew's Wonder Theatres, called for something "over the top". An apparently "one-off" Barton organ console provided the inspiration for the full-blown Wonder treatment (see the article by Clark Wilson included in the section on "PRODUCTION")

Windchest Design

Robert Morton organs initially continued to use many of the design developed by the California Organ Company, which were based on earlier, Murray Harris designs. With the advent of the "unit" style of organ specification, it became necessary to devise a reliable "unit windchest", each note having its own actuating electromagnet and valve pouch (and a further primary action pouch, if necessary).

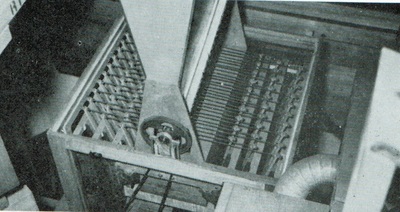

Because the earlier versions of the Robert Morton theatre organ were frequently a combination of both unit windchests and "straight" windchests, you will find many organs using the earlier California Organ Company style of straight windchest as well as the newer, post -1917 Robert Morton style of unit windchest. The picture at left shows an early Robert Morton "straight" windchest (with a diatonic pipe arrangement), used in a church organ built under the Robert Morton name..

Because the earlier versions of the Robert Morton theatre organ were frequently a combination of both unit windchests and "straight" windchests, you will find many organs using the earlier California Organ Company style of straight windchest as well as the newer, post -1917 Robert Morton style of unit windchest. The picture at left shows an early Robert Morton "straight" windchest (with a diatonic pipe arrangement), used in a church organ built under the Robert Morton name..

The Unit Windchest

Sometimes referred to as "box" windchests, these actions used large internal magnets with very large exhaust apertures; much larger than those used by Wurlitzer (the "Carlsted" windchests also used this magnet style). This made the extensive use of primary actions (smaller pouch/valves which exhausted the larger pouch/valves) less necessary for quick and responsive action. It also lessened the possibility of ciphers, because debris that might get caught between the armature and the magnet coil ends could more easily make its way out through the aperture. However, a persistent cipher usually meant having to get into the windchest and removing the magnet to clear it.

The "box" style windchests were usually chromatic in arrangement, although there are some instances of diatonic arrangement of pipes (the so called "M" style). Although they were fairly compact compared to other theatre organ windchests, they were also heavy, usually being found in two, three, four and five rank arrangements. Installation in a theatre always required rigging personnel and a lot of muscle.

The "box" style windchests were usually chromatic in arrangement, although there are some instances of diatonic arrangement of pipes (the so called "M" style). Although they were fairly compact compared to other theatre organ windchests, they were also heavy, usually being found in two, three, four and five rank arrangements. Installation in a theatre always required rigging personnel and a lot of muscle.

The Carlsted Windchest

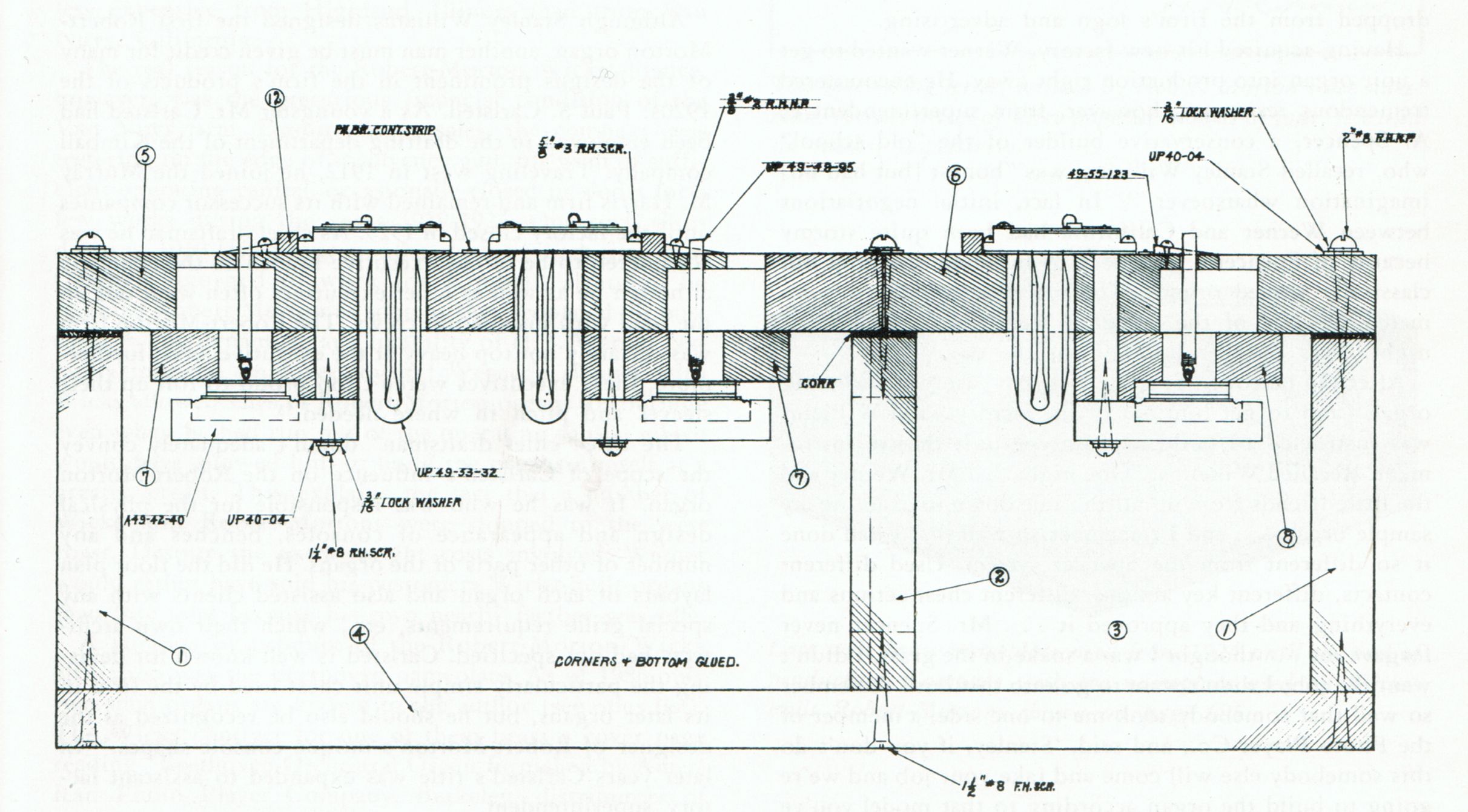

In about 1925, designer and draftsman Paul Carlsted developed a small, single rank windchest that greatly reduced the need for rigging in setting up and organ. These new windchests placed the pouches very close to the magnets which exhausted them, and because of this design, also made it possible to locate all the serviceable elements of the windchest on the bottomboard. If there was a problem, dropping the bottomboard would give you access to both magnets and pouches/valves, right there in your lap.

The large "bumblebee" magnets continued to be used, but pressures were increased, and in combination with the short distance between the pouch and the large magnet aperture, the actions became quite snappy and responsive.

The Carlsted windchests were lighter, but wider and less space efficient. They required a plenum at the end of a group of windchests for winding, but this also made it easier to wind specific stops off of specific reservoirs and tremulants. Post 1925, most Robert Mortons were installed with Carlsted style windchests, and by 1928, most were designed as high-pressure instruments, playing on 15" of wind.

The large "bumblebee" magnets continued to be used, but pressures were increased, and in combination with the short distance between the pouch and the large magnet aperture, the actions became quite snappy and responsive.

The Carlsted windchests were lighter, but wider and less space efficient. They required a plenum at the end of a group of windchests for winding, but this also made it easier to wind specific stops off of specific reservoirs and tremulants. Post 1925, most Robert Mortons were installed with Carlsted style windchests, and by 1928, most were designed as high-pressure instruments, playing on 15" of wind.

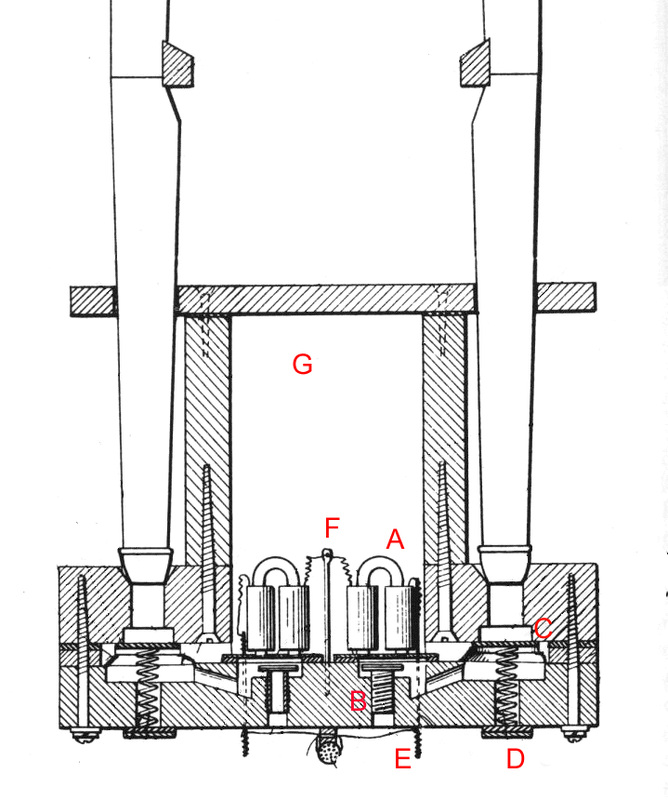

In the diagram above, the letters denote the following: (A) magnet; (B) magnet aperture, with adjustment for armature height; (C) pipe valve; (D) pouch return spring retaining disc, made of leather; (E) electrical connection to magnet; (F) return/common post, coming from magnet; (G) wind conveyance - the interior of the windchest. The top of the windchest doubled as the rackboard for the pipes.

The "Fotoplayer" Style Windchest

The smaller Robert Morton instruments, in a carry-over of the concepts of the American Photoplayer Company, needed to be compact, with a low sight-line and good accessibility for tuning and repairs. The windchest developed for this style of instrument actually sat on the floor -- it had no mechanism on the bottom of the windchest, only on the top. The tension on the valve springs (which returned the valves to seat against the bottom of the toeboards when the key was released) were adjustable via a sprung post which pulled against the valve from the top. The windchest used the Reisner C-17 "latchcap" style magnets.

Stops & Engraving

Robert Morton stop nomenclature evolved over time. Initially, they did not follow Wurlitzer's lead of calling divisions by names such as "Pedal", "Accompaniment", "Great" and "Solo". Instead, they referred to divisions by number, i.e. "Division I" = Pedal, "Division II" = Accompaniment, "Division III" = Great, "Division IV" = Solo. This practice persisted until at least 1921, when the factory adopted more standard division labels, probably in response to organist demands.

Robert Morton was also more fluid in their color-coding of stops than most other manufacturers. Early consoles would frequently have all ivory-colored stops, perhaps a hold-over from their church organ practice. At various points in the company's production you will find stops of unusual colors, such as pink and baby-blue, and of course, red, amber, brown and black. In fact, some consoles were produced with red, rather than ivory pistons. At some point, the company hit upon a stop color-coding scheme which worked this way:

Ivory, with black fill: Flutes, Tibias

Ivory, with black fill: Strings, with a black bar below the pitch designation, to differentiate it from the flutes

Ivory, with black fill: Inter and intramanual couplers. The coupler pitch was engraved inside a circle.

Red, with white fill: Brass/Foundation. This included chorus reeds and interestingly, Diapasons and Diaphones. These stops bore a black bar below the

pitch designation.

Red, with white fill: Woodwinds. This encompasses "lighter reeds", such as Clarinets, Oboes and Voxes.

Amber, mottled, with black fill: un-tuned percussions and traps

Brown, mottled, with white fill: tuned percussions, including piano

Black, with white fill: Tremulants

Robert Morton was also more fluid in their color-coding of stops than most other manufacturers. Early consoles would frequently have all ivory-colored stops, perhaps a hold-over from their church organ practice. At various points in the company's production you will find stops of unusual colors, such as pink and baby-blue, and of course, red, amber, brown and black. In fact, some consoles were produced with red, rather than ivory pistons. At some point, the company hit upon a stop color-coding scheme which worked this way:

Ivory, with black fill: Flutes, Tibias

Ivory, with black fill: Strings, with a black bar below the pitch designation, to differentiate it from the flutes

Ivory, with black fill: Inter and intramanual couplers. The coupler pitch was engraved inside a circle.

Red, with white fill: Brass/Foundation. This included chorus reeds and interestingly, Diapasons and Diaphones. These stops bore a black bar below the

pitch designation.

Red, with white fill: Woodwinds. This encompasses "lighter reeds", such as Clarinets, Oboes and Voxes.

Amber, mottled, with black fill: un-tuned percussions and traps

Brown, mottled, with white fill: tuned percussions, including piano

Black, with white fill: Tremulants

BRASS, WOODWINDS, COLOR REEDS & FOUNDATIONS

This photo presents examples of red stops, which were used for chorus reeds, color reeds and foundation stops like Diapasons.

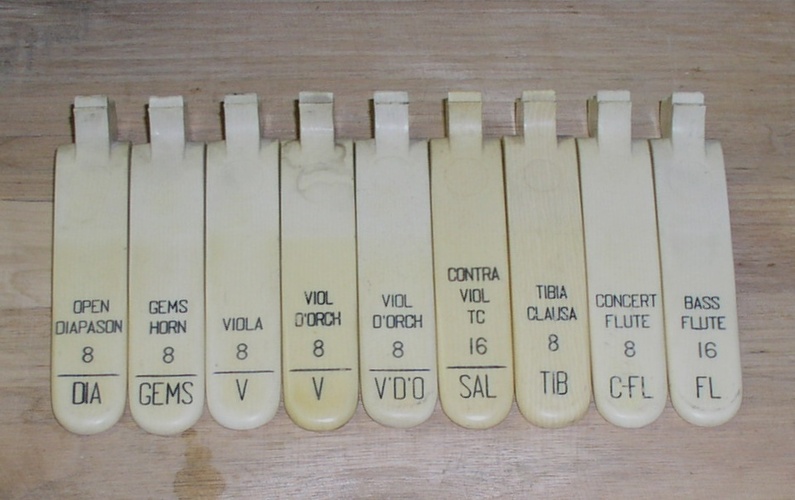

FLUTES, STRINGS & LIGHT FOUNDATIONS

White stops were used almost exclusively on earlier organs, but the coding system for strings remained in place, even after colors were used for other tonalities. Notice that the Open Diapason retains its "bar", even though that might tend to associate it with string tone.

TUNED PERCUSSIONS & COUPLERS

Tuned percussions were assigned to mottled brown, or "cocobolo" stops. RM's pragmatic abbreviations have some unusual results.

The couplers are usually white, with circled pitches to suggest their function. The black stops are from a church organ, and you may note that they are backrail stops (see below).

The couplers are usually white, with circled pitches to suggest their function. The black stops are from a church organ, and you may note that they are backrail stops (see below).

UNTUNED PERCUSSIONS & TRAPS, AND TREMULANTS

Untuned percussions were mottled amber, while tremulants were black (and to the point).

ENGRAVING, AND BACKRAIL STOPS

The engraving used on Robert Morton stops changed somewhat abruptly, right around 1924. Stop engraving at the factory was done on pantograph-style engravers. These devices used large representations of the stop legends, which were then reduced to the size on the stop by the pantograph mechanism. The original fonts were likely made of paper or cardstock, and the engraver operators would trace the stylus along the letter images on the cardstock, as steadily as possible. As a result, upon close inspection, one can find differences between the same letters on different stops. At sometime around 1924, the factory apparently acquired brass, bakelite or phenolic fonts, which were large, engraved fonts. This allowed the operators to run the stylus in the groove on the font, and the result was extremely consistent from stop to stop, organ to organ.

The picture above displays two early church-organ coupler stops, and "old" and "new" Tuba stops, Tibia stops and Diaphonic Diapason stops.

The picture above displays two early church-organ coupler stops, and "old" and "new" Tuba stops, Tibia stops and Diaphonic Diapason stops.

PAPER & BRASS FONTS

An example of paper fonts and brass fonts, on

the author's pantograph engraving machine.

the author's pantograph engraving machine.

ODDBALL STOPS

Clearly, Robert Morton's stop designs (color-coding and engraving) evolved over the years from 1917. Once they hit upon a "logical" color code, in about 1924, they didn't stray too far from it, although there are always anomalies here and there. In the earlier, four manual instrument for the Elks 99 Lodge in Los Angeles, California, blue and pink stops are present, and it really looks like they're trying out some new ideas -- the Diapasons are brown (with a bar), the strings are blue (no bar), and the Tibias are white with a bar. Couplers are black, with bars placed on some stops, but not others. Please note that the "dots" on the stops are "sticky paper" added more recently, and their function is irrelevant.

.

.

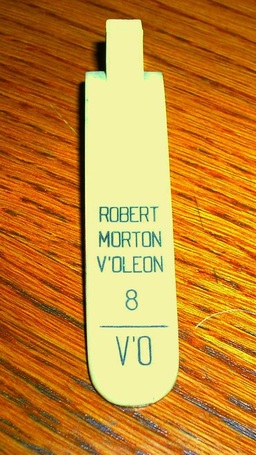

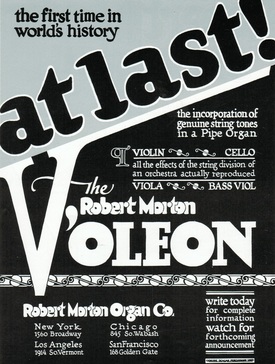

The v'oleon

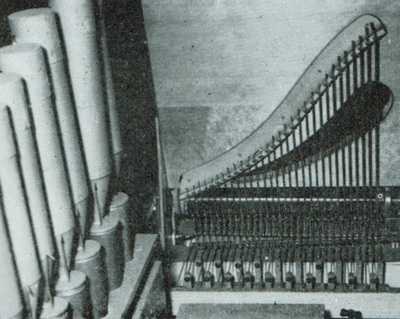

Robert Morton experimented with a number of devices designed to create special effects, but not all of them made it to the marketplace. The V'Oleon was one of the more interesting and musical products which came out of Robert Morton's "skunkworks", and the instrument was actually installed on a number of instruments, although we have no way to tell how many were sold and installed. The "mother of all Wonder Organs", the New Orleans Saenger Theatre organ, was equipped with a V'Oleon in its original configuration.

Invented by Harry L. Boynton, and adopted by Robert Morton in 1926, the V'Oleon employed actual "bowed" strings to create, essentially, authentic string tone that could be used in chords just like a set of organ pipes.

David Junchen describes the V'Oleon as follows: "Operation of the V'Oleon was simple and clever. Its strings were coiled and under only light tension, assisting them to remain in tune. Vacuum-operated pneumatics forced the strings in contact with a revolving roller, "bowing" them to produce tones. Any number of strings could be souunded simultaneously, allowing large chords to be played. A tremolo effect was achieved by means of a reciprocating felt'notched bar which gently wiggled the strings back and forth accross the revolving roller." (2:Vol.II, p.531)

The mechanism used was not unlike the simpler (and yet quite complex) mechanisms incorporated into many automatic musical instruments which played piano and violin mechanically. The advantage was that there were more strings than were available on a violin or cello, so more notes could be played at the same time -- making an effect which was more-or-less orchestral in nature.

Invented by Harry L. Boynton, and adopted by Robert Morton in 1926, the V'Oleon employed actual "bowed" strings to create, essentially, authentic string tone that could be used in chords just like a set of organ pipes.

David Junchen describes the V'Oleon as follows: "Operation of the V'Oleon was simple and clever. Its strings were coiled and under only light tension, assisting them to remain in tune. Vacuum-operated pneumatics forced the strings in contact with a revolving roller, "bowing" them to produce tones. Any number of strings could be souunded simultaneously, allowing large chords to be played. A tremolo effect was achieved by means of a reciprocating felt'notched bar which gently wiggled the strings back and forth accross the revolving roller." (2:Vol.II, p.531)

The mechanism used was not unlike the simpler (and yet quite complex) mechanisms incorporated into many automatic musical instruments which played piano and violin mechanically. The advantage was that there were more strings than were available on a violin or cello, so more notes could be played at the same time -- making an effect which was more-or-less orchestral in nature.

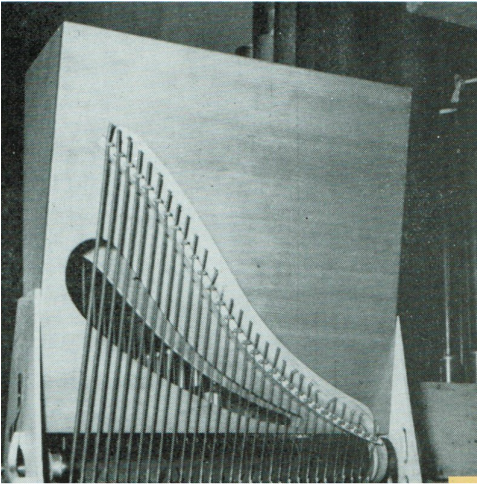

Unfortunately, the V'Oleon's volume was hampered by the limitations of acoustic amplification. The resonating box of the V'Oleon was designed to be horn-shaped, in order to project the sound effectively; but buried in an organ chamber, behind swell shades, and in the company of pipework on 10" and 15" of wind pressure, the instrument was quiet at best, and inaudible at worst, particularly in a large theatre. When the Saenger organ was enlarged, the V'Oleon was replaced by the "Vibrato Strings" stop, a compound stop utilizing organ sttring pipes. There are few surviving examples extant.

In retrospect, the device might have been more successful, if its application were limited to Robert Morton's output of smaller instruments, destined for smaller theatres.

In retrospect, the device might have been more successful, if its application were limited to Robert Morton's output of smaller instruments, destined for smaller theatres.