PRODUCTION

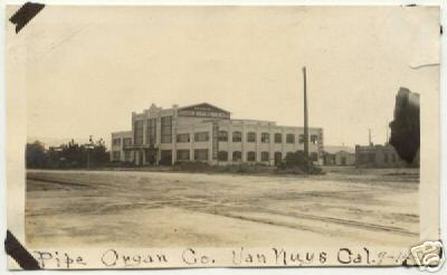

The Robert Morton Factory

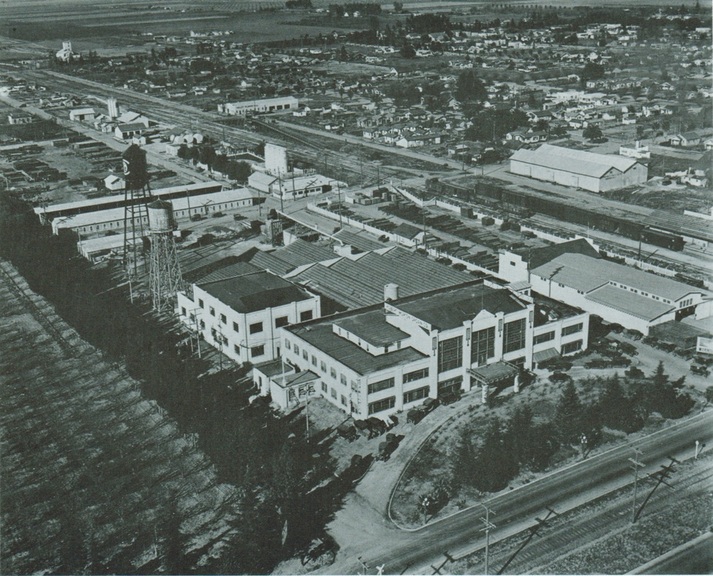

PHOTO I

Established in Van Nuys as the Johnston Organ & Piano Company, the factory building had borne the names of at least three pipe organ building enterprises before it was torn down in 1964; Johnston Organ & Piano Company, California Organ Company, and finally the Robert Morton Organ Company..

Located in Van Nuys, California, at the corner of Van Nuys Boulvard and Oxnard Street, the factory sprawled over several acres. With a major rail line right next to it, and a huge lumberyard just across the street, the site had access to direct delivery of the raw materials needed to build a pipe organ -- wood, metal, wire, and parts both small and large. The finished product could then ship out via truck or those same rail lines.

The real estate developers who spurred the construction of the factory did so with the intent that it would draw people to the San Fernando Valley, and who would buy houses there -- houses that they were building and selling. Their scheme apparently worked; at the height of its production, the Robert Morton employed about 360 people at the Van Nuys factory *(4 : 6), and was one of the largest businesses established in the budding community and in the San Fernando Valley.

Located in Van Nuys, California, at the corner of Van Nuys Boulvard and Oxnard Street, the factory sprawled over several acres. With a major rail line right next to it, and a huge lumberyard just across the street, the site had access to direct delivery of the raw materials needed to build a pipe organ -- wood, metal, wire, and parts both small and large. The finished product could then ship out via truck or those same rail lines.

The real estate developers who spurred the construction of the factory did so with the intent that it would draw people to the San Fernando Valley, and who would buy houses there -- houses that they were building and selling. Their scheme apparently worked; at the height of its production, the Robert Morton employed about 360 people at the Van Nuys factory *(4 : 6), and was one of the largest businesses established in the budding community and in the San Fernando Valley.

A Bombarde for Bovard

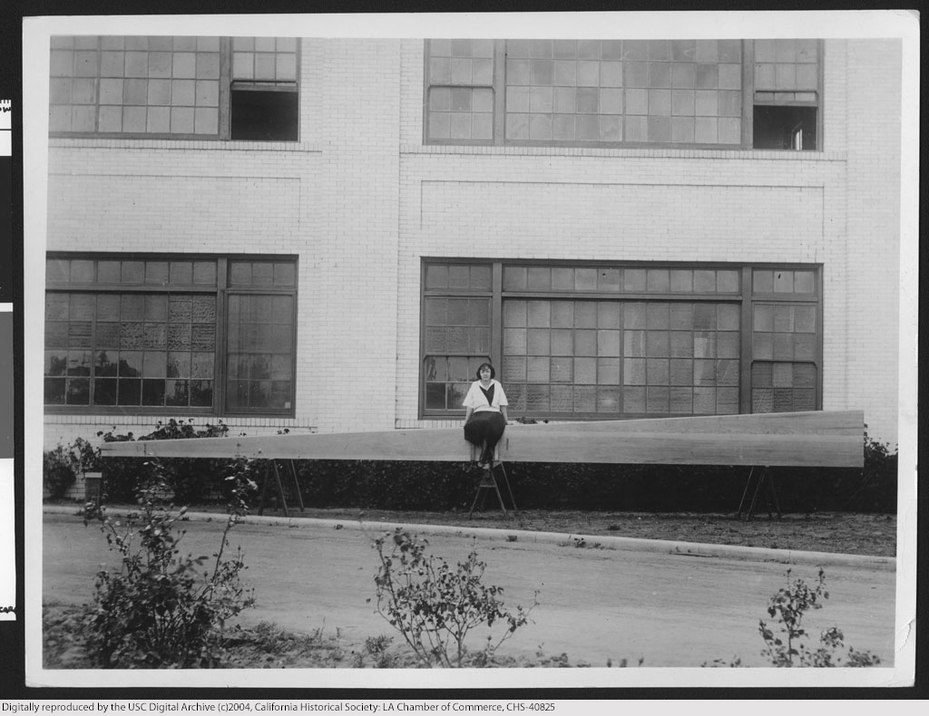

From the USC Photo Archives

The only 32' stops made by Robert Morton were for the organ in Bovard Auditorium on the campus of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. These were a 32' Bombarde and a 32' Open Diapason of wood (which now resides in the organ at the "Crystal Cathedral" in Garden Grove, California).

Since the dismantling and dispersal of the Bovard Auditorium organ, the 32' Bombarde seems to have disappeared. It is possible that it may reside somewhere in an organ the Southern California area, waiting to be discovered.

Since the dismantling and dispersal of the Bovard Auditorium organ, the 32' Bombarde seems to have disappeared. It is possible that it may reside somewhere in an organ the Southern California area, waiting to be discovered.

A 32' Open diapason

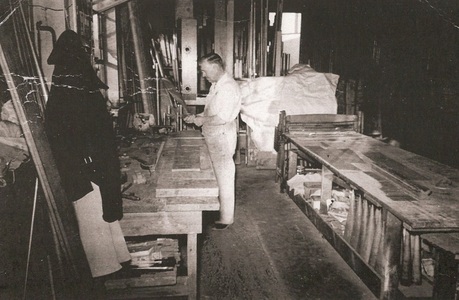

Members of the wood and metal pipe departments celebrate the "big one" / / /

From the Collection of Tammy Bain, grand-daughter of Archie March, Jr.

Although Robert Morton built man wood 16' Diaphones, no 32' Diaphones were built. For the classical specification of the Bovard organ, a 32' Open Diapason was included and this the low CCCC of that stop. Pipemaker Archie March, Sr. stands fourth to the right of the seam in the middle of the pipe; Archie March, Jr. stands just to the right of the seam. When the Bovard organ was dispersed, this set of pipes went to the organ in the "Crystal Cathedral" where, painted gray, it continues to sound forth. Note the comfy fellow sticking out of the top end of the pipe, and the tiny wood pipe which is standing in the mouth. Archie March Jr. noted that when this stop was first tested on the erecting room floor, it blew out three windows in the building. . .

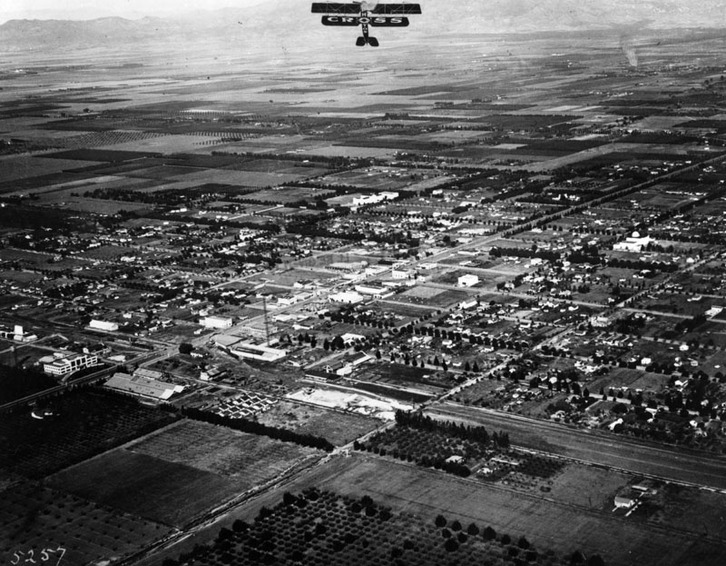

VAN NUYS From the Air. . .

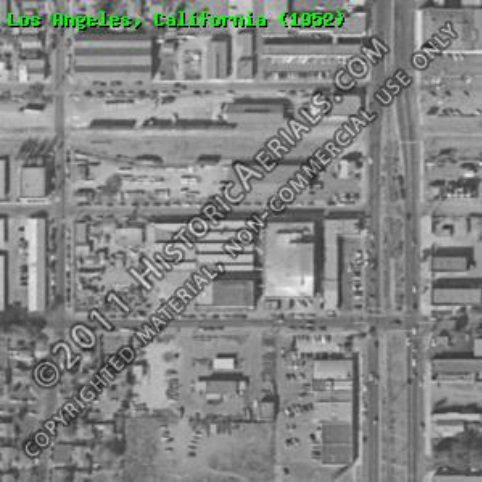

PHOTO VI

In the early teens, the San Fernando valley was a mix of semi-desert and irrigated agricultural land, ripe for developers. In this aerial photo, taken circa 1916, you can see the young California Organ factory on the far left, with the curved driveway. Across the street is a large lumberyard (convenient!). It is likely that many of the small houses in this picture belonged to employees of the organ factory!

The Big Picture

PHOTO VII

An excellent aerial view of the Van Nuys factory, likely at the height of its production in 1927 or 1928. Notice the developing expanses of residential neighborhoods in the background, the very thing the initial backers of the Johnston organ firm hoped to accomplish. The next image is a 1952 aerial view, showing that a good part of the facility was still there. It was all torn down in 1964.

Today, the area around Van Nuys and Oxnard Boulevards is largely occupied by auto dealerships, and the extensive rail lines are all gone.

STOCK PRODUCTION MODELS

Interestingly, although the Robert Morton company offered a standardized line of instrument models, just like Wurlitzer, the model designations are rarely applied to Robert Morton instruments today. So, although the terms "Style D" Wurlitzer, "Style 210 Special" and other Wurlitzer designations can instantly bring a specification and configuration to the minds of the knowledgeable, that is less so with Robert Morton organs. It appears that initially, the company offered standardized models lettered "A, B. and C" (4 : 6)

Unlike the Wurlitzer firm, for which a plethora of advertising and firm records still exist, few of the factory records, advertising brochures, or contracts have survived. Like Wurlitzer, Robert Morton appears to have had a range of "stock models" or specifications from which they worked, although given the fluidity of the company, these likely changed significantly over the years, particularly after the reorganization of 1924.

Here, we have attempted to reconstruct a rough idea of the models available, and what the customer was getting. Bear in mind that organs of over seven ranks did not make use of the in-console relay system that Robert Morton's smaller organs used. For organs of four ranks, the company was able to eliminate the necessity of a key relay, since the contacts under the keys took its place, and simply went directly to the switchstacks in the console. This made for a very compact instrument which was much less expensive than the organs requiring an external key relay and switchstack.

/////

Rough-out of style designations

ROBERT MORTON STYLE DESIGNATIONS

(from Junchen)

A

B. . . . . . . . . . 2/4

C

LS-M . . . . . 3/?

8. . . . . . . . . . 2/

14 . . . . . . . . 2/

16 . . . . . . . . 2/4

17 . . . . . . . . 2/5 -- (1926)

18 . . . . . . . . . 2/6

18-N . . . . . . 2/6

19 . . . . . . . . . 2/7

20 . . . . . . . . 2/8

21-N . . . . . . 3/

22 . . . . . . . . . 2/10

23-N . . . . . . 2/11

24 . . . . . . . . 2/11

25 . . . . . . . . . 2/12

25-M

27 . . . . . . . .. . 2/2

39 . . . . . . . . . 2/3

39A . . . . . . . . 2

39R . . . . . . . 2/4

49 . . . . . . . . 2/3. -- (10"wp 30"vac); roll player? Flute, String, _____ // roll player?

49C . . . . . . . 2/4

49D. . . . . . . . 2/ -- 4 ranks?

49H . . . . . . . 2/

59 . . . . . . . . . 2/

75 . . . . . . . . . 2/4 -- 10"wp

85 . . . . . . . . . 2/5

100 . . . . . . . -- 2/? (192-)

160 . . . . . . . . 2/5

176

177-E . . . . . . 2/7

179

183 . . . . . . . . 3/

187

188

200 . . . . . . . 2/10

200CX. . . . 2/12

250

290

300 . . . . . . . 3/14

NOTES RE "STYLE" LIST // This is nuts. Multiple 2/4 style designations with not a clue as to when the style was active, or if it was superceded, or what the differences were in contemporary model numbers for organs of the same size.. Not too useful.

Unlike the Wurlitzer firm, for which a plethora of advertising and firm records still exist, few of the factory records, advertising brochures, or contracts have survived. Like Wurlitzer, Robert Morton appears to have had a range of "stock models" or specifications from which they worked, although given the fluidity of the company, these likely changed significantly over the years, particularly after the reorganization of 1924.

Here, we have attempted to reconstruct a rough idea of the models available, and what the customer was getting. Bear in mind that organs of over seven ranks did not make use of the in-console relay system that Robert Morton's smaller organs used. For organs of four ranks, the company was able to eliminate the necessity of a key relay, since the contacts under the keys took its place, and simply went directly to the switchstacks in the console. This made for a very compact instrument which was much less expensive than the organs requiring an external key relay and switchstack.

/////

Rough-out of style designations

ROBERT MORTON STYLE DESIGNATIONS

(from Junchen)

A

B. . . . . . . . . . 2/4

C

LS-M . . . . . 3/?

8. . . . . . . . . . 2/

14 . . . . . . . . 2/

16 . . . . . . . . 2/4

17 . . . . . . . . 2/5 -- (1926)

18 . . . . . . . . . 2/6

18-N . . . . . . 2/6

19 . . . . . . . . . 2/7

20 . . . . . . . . 2/8

21-N . . . . . . 3/

22 . . . . . . . . . 2/10

23-N . . . . . . 2/11

24 . . . . . . . . 2/11

25 . . . . . . . . . 2/12

25-M

27 . . . . . . . .. . 2/2

39 . . . . . . . . . 2/3

39A . . . . . . . . 2

39R . . . . . . . 2/4

49 . . . . . . . . 2/3. -- (10"wp 30"vac); roll player? Flute, String, _____ // roll player?

49C . . . . . . . 2/4

49D. . . . . . . . 2/ -- 4 ranks?

49H . . . . . . . 2/

59 . . . . . . . . . 2/

75 . . . . . . . . . 2/4 -- 10"wp

85 . . . . . . . . . 2/5

100 . . . . . . . -- 2/? (192-)

160 . . . . . . . . 2/5

176

177-E . . . . . . 2/7

179

183 . . . . . . . . 3/

187

188

200 . . . . . . . 2/10

200CX. . . . 2/12

250

290

300 . . . . . . . 3/14

NOTES RE "STYLE" LIST // This is nuts. Multiple 2/4 style designations with not a clue as to when the style was active, or if it was superceded, or what the differences were in contemporary model numbers for organs of the same size.. Not too useful.

Personnel

PHOTO IX

DO YOU RECOGNIZE ANY OF THESE PEOPLE?

Row 1 (front) - 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Row 2 - 1, 2 3, 4, 5, Stanley Williams, Harold Werner?, Henry "Cocky" Charles?, 9, 10, 11, 12

Row 3 - 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Row 4 - 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Many of the individuals who participated in the building of the Robert Morton product were previously employees of the California Organ Company, the Johnston Organ Company, the Los Angeles Art Organ Company and the Murray M. Harris Organ Company. In fact, after the company's operations were moved to the plant in Van Nuys, although the name of the company went through many changes, most of the staff stayed the same, doing the things that they had always done.

According to an interview with Richard Simonton (The Console, November 1965, p.16), experienced workmen at the factory were earning around $4.00 per hour by the mid 1920's. Of course, after the reorganization of 1924-25, the paychecks also came on time, which wasn't always the case in the early days.

We've attempted to compile a list of employees and what sort of work they did for the company, and where possible, a more comprehensive look at their lives and their contributions to Robert Morton and the pipe organ industry. This list will be in a constant state of flux as we acquire more information about the workforce employed by Robert Morton. This list includes all of those individuals who are known to have worked for Robert Morton from 1917 until the closing of the factory in 1931.

Abrams, A.L. (b:?, d:?) With American Photo-Player firm in Berkeley; may have been office staff at San Francisco headquarters.

Abrams, Sylvain S. (b:?, d:?) Vice President of RM at its inception in May of 1917.

A.L. Armuth

Roy Arnovitch

Fred F. Auer (b:?, d:?) "Incorporator" with American Photo-Player firm.

B.T. Bean (b:?, d:?) A member of Klink, Bean & Co., accountants; became accountant/incorporator for American Photo-Player firm.

Wilbur R. Bergstrom, head of machine shop, which turned out pipe mandrels, scrapers, and a myriad of metal parts used to build Robert Morton organs. Mr. Bergstrom may also have been involved in installation work.

C.E. Bloom

James Bolton, pipemaker (b:1884, d:?). James Bolton appears to be related to the famous Boltons of Skinner fame, all pipemakers and voicers. Frederick Bolton (who worked for Murray M. Harris from 1900 to 1904) was his father. Emigrating from Liverpool, England in about 1889, he worked as a pipemaker with the Samuel Pierce Organ Pipe firm in Reading, MA, 1907-1911; Farrand & Votey, Detroit, MI; E.M. Skinner, Boston., MA in 1921, followed by the Schoenstein firm in San Francisco. He initially established a shop in Berkeley, California, along-side Thomas Whalley from 1928 to 1930. Although it appears that his pipe shop was independent, he certainly developed a relationship with the American Photo Player Company, and supplied pipes to Photo Player, and perhaps also to Robert Morton. Eventually, he moved (or established) his shop in Southern California, and supplied pipes to the Artcraft Organ Company in Santa Monica, as well as to others. He may have established his pipe shop on the Artcraft premises at some point. Anecdotal information indicates that he had done work for Robert Morton at the Van Nuys factory, although it is not clear if this was as an employee or an independent contractor.

Philip C. Carlstedt - With American Photo-Player Co., before 1918

Paul S. Carlsted (b. 4/1/1891, d. 5/1/1982) Carlsted was a draftsman (much to add here -- feature article)

Joseph J. Carruthers (b:1855, d:1937) Originally with Hope-Jones firm in Birkenhead, England, c. 1894. With Norman & Beard, Norwich, England, c. 1897. Emigrated to United States c. 1904 to work with Hope-Jones firm (superintendent) in Elmira, NY. Joined Wurlitzer firm in 1910; Kimball 1914; Wangerin, 1917. May have worked for RM after 1917, dates unclear.

Henry J. Carruthers (b:?, d:?) Son of Joseph Carruthers. With Hope-Jones firm from 1904-05; E.M. Skinner 1905-06; Hope-Jones in Elmira 1907-10, Wurlitzer in 1910. With Steere & Sons, Springfield, MA until 1917.. Became voicer with RM in 1917, but went to Kimball in 1919. From 1920, he operated an organ service firm in the Pacific Northwest.

Elmer M. Chicken (b. 1862)

Edward Crome (b. 1872)

George F. Detrick

John Dewar - California Organ Co.

Roger Eaton

W.F. Eaton

Robert P. Elliot, vice-president, general manager of California Organ Company, October 1916.. Elliott had been president of the short-lived Hope-Jones Organ Company, and came to the California company just before it became Robert-Morton, with the advent of RM's unit-style organs. Elliott was not enamored of the new "unified" instruments and so eventually left the firm in May of 1918 to join the Kimball company as general manager. He also worked for the Welte Organ Company. (2 : 495, 498)

V.H. Falk

Hubert C. Ferris, installer

Oliver C. Frame (b. 1854) -- Installer. Began with Murray M. Harris in 1900, and remained through Robert Morton period.

Walter Gibson (b. 1870, England) -- Began with Murray M. Harris in 1900, and remained through Robert Morton period. Did installation work and ? Was involved with the installation of the 1904 World's Fair organ.

M.F. Goldberg

George Head (b. 1863, England) -- Decorator (facade pipe stenciling, gilding, etc.)

Charles Hershman, installer. Participated in installation of Bovard Auditorium organ (6 : A)

York Hoffman

Val Holzinger, with RM until 1924, then went to work for the Wurlitzer Company. Subsequently, he was employed by the Maas Organ Company (started by Louis Maas, also an RM employee), and ultimately started his own firm, manufacturing low-cost church organs in the 50's and 60's. Holzinger Organ Company also employed Archie March, Jr. as a pipe maker.

Earl B. Hough

T.P. Jordan

Bert Kingsley (Kinsley), (b:1875, d.1939) head voicer, previously with the Samuel Pierce Pipe Organ Company, Estey Organ Company, M.P. Moller Organ Company, and Pilcher Organ Company.

E.B. Kittleman - California Organ Co.

Louis Maas (b:?; d:1955). Previously employed by Eilers Music Co. in San Francisco and Sherman-Clay, and also as a service rep for Wurlitzer (c.1914). Joined Robert Morton c. 1917, and left in 1922 to open his own firm (Maas Organ Co., in Los Angeles). Joined by Carl Riedler in 1934 and Paul Rowe, Sr in 1947.

William R. McArthur

Charles McQuigg (b. 1882) -- Originally with Murray M. Harris, he stayed on through the company name changes and worked with Robert Morton. Capacity unknown.

F.W. Miller

Henry A. Niver - American Photo-Player / California Organ Co.

Carl Pearson (b.1872 or 1885; d.1986), Console Department Supervisor. Originally from Sweden, Carl emigrated to America with his family to continue his career in organ work. Previously with the Hutchings Organ Company, Boston, Massachusetts, Estey Organ Company, and then finally with the Los Angeles Art Organ Company. He remained through the changes in management and ownership, including moving his family to Van Nuys when the factory was moved to the San Fernando Valley. According to the younger Pearson, the initals "C.P." appeared inside every console that he had completed, and A.C. continued this practice after he became head of the Console Department.

He apparently also did maintenance of pipe organs in the area on his own, and employed his son (below) to assist and hold keys. (4 : 12)

Arthur C. Pearson, (B?;d?), relay/electrical; later head of the Console Department. Started in the console department as a part-time employee under his father's tutelage in 1923, while he was in his teens. His first job was "boring at least one hundred thousand holes and channels in relay actuating racks" (4 : 12) After his tenure at Robert Morton, he became an electrical engineer. After 1924, he became a full time employee, remaining with the firm until its closure, and then working for C.B. Sartwell in 1933.

Benjamin Platt

Carl Riedler (b.1880; d.1955). Born in Weickersheim, Germany, and emigrated to the U.S. in 1903. Worked for August Laukhuff in Weickersheim, Walcker of Luwigsburg, Wirsching of Salem, OH, and Wangerin-Weickhardt of Milwaukee, WI for 15 years as head voicer. Came to Robert Morton in 1923, and apparently made a home in Van Nuys, California. He likely worked as a voicer for Robert Morton until the factory closed, Employed by Maas Organ Co., Los Angeles in 1934.

Thomas Ross, pipemaker, and metalworker. Started with Murray M. Harris in 1900. (1 : 308)

Buster Rosser, reservoir department.; installer. In later years, worked on installation of Redwood City Sequoia Theatre 3/13 at Lorin Whitney's recording studio in Glendale California. Also worked on Buddy Cole studio installation.

B.L. Samuels

Carl B. Sartwell, Assistant Superintendent/ Purchasing Agent.. Nicknamed "Happy", C.B. Sartwell had roughly the same duties as Stanley Williams, overseeing the various departments of the factory. Ultimately, Sartwell became the owner of the Robert Morton name, and its remaining assets, operating out of small building on

David Schaub - California Organ Co.

Leo Schoenstein, superintendent. Schoenstein succeeded Williams as Superintendent after Williams left to work for Kimball (4 : 21)

Frederick Sherman

E.A. Spencer, superintendent, California Organ Company; superintendent at American Photo Player Company from 1917 - 1922. Then left the company and started Spencer Organ Company in Pasadena, California.

A.E. Streeter - American Photo-Player Co./ California Organ Co.

Herb W. Sutton, metal casting shop supervisor, pipemaker.

R.E. Tinker, pipe maker and/or voicer; name found on a Fotoplayer Diapason stop

Hal Van Valkenberg

James Edgar Varnum (b.1872)

John William Whitely (1864 - 1940) -- Voicer. Worked with Casson, Hope-Jones and Michell & Thynne; also as a voicer with Los .Angeles. Art Organ Co (1903-1905). May have continued with Robert Morton.

ROBERT MORTON INSTALLATION CONTRACTORS

Balcom & Vaughan, Seattle, WA

Schoenstein & Co., San Francisco, CA

Roy Gimpel -- installer in the southern states, usually painted windlines red.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Anecdotal and other personnel information has been supplied by Tammy Bain, Jim Lewis, and Jim Spohn.

Archie march, senior & junior

Archibald March, Sr (b. ?, d. 1962)., pipemaker

Archibald D. March, Jr. (b.1895; d.1966, pipemaker The "Archie"March father and son team emigrated from England in 1906. March, Sr worked for the Estey Organ Company in Brattleboro, Vermont for a number of years, and then found employment, along with his son, at The Hall Organ Company, in New Haven, Connecticut. They both came to the house of Wurlitzer in about 1910, where a number of former Hope-Jones alumni were working. In the early twenties, the Robert Morton Company placed ads in trade magazines offering work to pipemakers, which they desperately needed, and as a further incentive provided train fare to those who were interested, providing that they stayed with the company for at least six months. The March family took advantage of this offer, and remained until the factory closed its doors in the early thirties. (4 : 14)

When the elder March retired, the younger continued on in the pipe department. Pipes of fine construction bearing the flowing script of Archie March, Senior and Junior are common in Robert Morton organs.

Archibald D. March, Jr. (b.1895; d.1966, pipemaker The "Archie"March father and son team emigrated from England in 1906. March, Sr worked for the Estey Organ Company in Brattleboro, Vermont for a number of years, and then found employment, along with his son, at The Hall Organ Company, in New Haven, Connecticut. They both came to the house of Wurlitzer in about 1910, where a number of former Hope-Jones alumni were working. In the early twenties, the Robert Morton Company placed ads in trade magazines offering work to pipemakers, which they desperately needed, and as a further incentive provided train fare to those who were interested, providing that they stayed with the company for at least six months. The March family took advantage of this offer, and remained until the factory closed its doors in the early thirties. (4 : 14)

When the elder March retired, the younger continued on in the pipe department. Pipes of fine construction bearing the flowing script of Archie March, Senior and Junior are common in Robert Morton organs.

harold j. werner

(b. 1877, d.1937) Harold J. Werner, president of the American Photoplayer Company, Berkeley, California (the parent company of Robert Morton).

Described by many as a man of short stature but great energy, Harold Werner was the prime mover of the Robert Morton company from the beginning. Perhaps the estimate of one's colleagues is the greatest praise -- R.P. Matthews said that "Werner may have been a small man in stature, but he was a really big man in all other ways. He was dynamic, a terrific guy, a real wonder! He was the kind of fellow who never kept track of his finances (which turned out to be a fatal flaw -- ed.). He never knew what his expenses were because he was not a man to worry about little things. Werner was an excellent organizer and was all the time doing things that on the surface did not look to be kosher, but were so far as he was concerned, and did them without trying to mislead anyone. He wanted to see the Morton organ become the leader in the field and worked toward that goal constantly. Werner did everything to start the American Photo Player Company and the Robert Morton Pipe Organ Company. He alone was responsible for both. It was a terrible blow to him to be thrown out of the companies. However, he was a tremendous optimist and you couldn't keep him down for long. He might be gloomy for a day or two, but he always bounced back to the bright side.

"After losing his two companies, he sold Moller organs and, I believe, was the man responsible for the big Moller going in the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. Some time later he opened an insurance business in San Franscisco. Returning to the Bay area from a business meeting in Los Angeles, he picked up a hitchhiker and asked him to drive -- he hated driving. There was an accident; a truck hit Werner's car and both men were killed. The hitchhiker was behind the wheel."

"In my opinion, Werner lost the two companies because he was careless about details. He would give you anything you wanted, and if he wanted something for the organization, he did everything in his power to get it." (4 : 23)

Lack of attention to financial matters was Werner's Achilles heel. A rumor surfaced that Werner was selling organs in the East, obtaining the money for them and then pledging the contracts again in the West to get more money; what is called hypothecation of contracts. Most Robert Morton employees were unaware of this, but Stanley Williams had heard the rumor -- "I noticed that finances were rather strange. But I had nothing to do with them; I was hired as factory superintendent to look after the product. But one morning a friend of mine at the bank in Van Nuys said, ' You know, Williams, it's rather strange, we advance the payroll on Saturday and we don't get a check until Monday to cover it. And we don't know where the check is coming from. Sometimes it's from New York, other times from St. Louis, and it all seems very odd.'" (4 : 21)

"This was very disturbing to me because we got enormous prices for these machines. And then a more extraordinary thing happened. Word came to me through the bank that an organ would be hypothecated twice. If an organ were sold in St. Louis, the purchaser, unsuspectingly it was said, would sign two contracts. One was supposed to be for the New York office and the other for the local office. What happened, I was informed, was the same contract was being hocked twice, one in the East and one out here." (4 : 21)

"This was just about the time I dreamed of making a change to sell organs instead of build them." In fact, Williams left the firm almost a year before the firm closed its door and was reorganized in 1924-25.

The firm's corporate charter was suspended on March 1, 1924 for failure to pay franchise taxes (sales taxes), and this meant that Robert Morton could no longer transact business in California. Prior to this, some of the executives of the Photo Player firm were working quietly behind the scenes, unknown to Werner, to seek new capital sources to sustain the business. Ultimately, the firms creditors stepped in and forced the reorganization of the companies. At this point, Mortimer Fleischacker entered the scene, and essentially saved the company and brought about its complete reorganization (see "History"). H.J. Werner was ousted as head of both companies, sued and stripped of all of his stock.

At the same time, he was cleared of any charges of financial shenanigans, fraud or embezzlement, and the rumors about dual hypothecation of contracts was proven to be groundless (and in fact resulted from the mergers of one or more banks that created the illusion of dual hypothecation). But Werner's lack of attention to financial matters proved to be his undoing, a sorry end for his role in creating one of the great theatre organ builders in America..

Described by many as a man of short stature but great energy, Harold Werner was the prime mover of the Robert Morton company from the beginning. Perhaps the estimate of one's colleagues is the greatest praise -- R.P. Matthews said that "Werner may have been a small man in stature, but he was a really big man in all other ways. He was dynamic, a terrific guy, a real wonder! He was the kind of fellow who never kept track of his finances (which turned out to be a fatal flaw -- ed.). He never knew what his expenses were because he was not a man to worry about little things. Werner was an excellent organizer and was all the time doing things that on the surface did not look to be kosher, but were so far as he was concerned, and did them without trying to mislead anyone. He wanted to see the Morton organ become the leader in the field and worked toward that goal constantly. Werner did everything to start the American Photo Player Company and the Robert Morton Pipe Organ Company. He alone was responsible for both. It was a terrible blow to him to be thrown out of the companies. However, he was a tremendous optimist and you couldn't keep him down for long. He might be gloomy for a day or two, but he always bounced back to the bright side.

"After losing his two companies, he sold Moller organs and, I believe, was the man responsible for the big Moller going in the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. Some time later he opened an insurance business in San Franscisco. Returning to the Bay area from a business meeting in Los Angeles, he picked up a hitchhiker and asked him to drive -- he hated driving. There was an accident; a truck hit Werner's car and both men were killed. The hitchhiker was behind the wheel."

"In my opinion, Werner lost the two companies because he was careless about details. He would give you anything you wanted, and if he wanted something for the organization, he did everything in his power to get it." (4 : 23)

Lack of attention to financial matters was Werner's Achilles heel. A rumor surfaced that Werner was selling organs in the East, obtaining the money for them and then pledging the contracts again in the West to get more money; what is called hypothecation of contracts. Most Robert Morton employees were unaware of this, but Stanley Williams had heard the rumor -- "I noticed that finances were rather strange. But I had nothing to do with them; I was hired as factory superintendent to look after the product. But one morning a friend of mine at the bank in Van Nuys said, ' You know, Williams, it's rather strange, we advance the payroll on Saturday and we don't get a check until Monday to cover it. And we don't know where the check is coming from. Sometimes it's from New York, other times from St. Louis, and it all seems very odd.'" (4 : 21)

"This was very disturbing to me because we got enormous prices for these machines. And then a more extraordinary thing happened. Word came to me through the bank that an organ would be hypothecated twice. If an organ were sold in St. Louis, the purchaser, unsuspectingly it was said, would sign two contracts. One was supposed to be for the New York office and the other for the local office. What happened, I was informed, was the same contract was being hocked twice, one in the East and one out here." (4 : 21)

"This was just about the time I dreamed of making a change to sell organs instead of build them." In fact, Williams left the firm almost a year before the firm closed its door and was reorganized in 1924-25.

The firm's corporate charter was suspended on March 1, 1924 for failure to pay franchise taxes (sales taxes), and this meant that Robert Morton could no longer transact business in California. Prior to this, some of the executives of the Photo Player firm were working quietly behind the scenes, unknown to Werner, to seek new capital sources to sustain the business. Ultimately, the firms creditors stepped in and forced the reorganization of the companies. At this point, Mortimer Fleischacker entered the scene, and essentially saved the company and brought about its complete reorganization (see "History"). H.J. Werner was ousted as head of both companies, sued and stripped of all of his stock.

At the same time, he was cleared of any charges of financial shenanigans, fraud or embezzlement, and the rumors about dual hypothecation of contracts was proven to be groundless (and in fact resulted from the mergers of one or more banks that created the illusion of dual hypothecation). But Werner's lack of attention to financial matters proved to be his undoing, a sorry end for his role in creating one of the great theatre organ builders in America..

stanley w. williams

Stanley W. Williams (1881 - 1971), superintendent from 1917 through 1922. Williams had apprenticed with Robert Hope-Jones in England, and emigrated to the United States in 1906, working first for the short-lived Electrolian Company (which was a brief spin-off from the Los Angeles Art Organ Company), and then ultimately coming to work for the reorganized Murray Harris firm in 1911. He remained with the firm through its many name changes, and was responsible for the design and construction of the first Robert-Morton theatre organ. He left Robert Morton at the behest of R.P Elliott in 1922, during one of it's more serious financial stumbles, to join W.W. Kimball in Chicago. (1 : 310)

Stanley Williams can be credited with the vision of the first incarnation of the Robert Morton theatre organ. He had mixed feelings about theatre organs, and really preferred the classical instrument. In speaking of his endeavors re "opus one" he recalled:

"One night at the very beginning of the association with American (American Photplayer; ed), when I was building the two manual unit job, Mr. Werner and some of the men from Berkeley came in to examine my sample. It was much different than the classic instruments they had seen on the floor, the ones designed by Spencer. In its construction I used different contacts, key actions, chest actions and they approved it without change.

"Later on, Mr. Spencer was sent to the Fotoplayer factory in Berkeley as head of the works. He really never forgave me for siding with the American Photo Player people. Subsequently I was made superintendent of the Van Nuys plant. I never was too enthusiastic about the change and didn't want the job, but I remember so well that somebody took me aside during one of the organizational meetings -- he was a Photo Player Company man -- and told me: ' Stanley, if you don't do this somebody else will come and take over your job, and we're going to build the organ according to the model you've designed. You might just as well do it yourself. You are not being disloyal to Mr. Spencer because he is out. He just doesn't understand what we want to do.' And that was actually how I got into building the Morton.

"I had been brought up by Robert Hope-Jones on his famous unit system which I had more or less forgotten about until the change was made at Van Nuys. In looking back, I do not particularly point with pride to the unit system, but with a touch of regret because the organs that were built on the unit system in general were pretty poor things as organs. They made satisfactory noises for accompanying movies but for the rendition of music they -- well, music wasn't composed for them. It was like expecting an inferior brass band to play the great works of music.

"Anyway, the first organ I built on the unit design, a two manual instrument, eventually went into the California Theatre in Santa Barbara and stayed there for quite a long time. This was strictly an eye-opener -- to find that Wurlitzer wasn't the only firm to have a man who could design a unit orchestra."

(4 : 3)

Stanley Williams can be credited with the vision of the first incarnation of the Robert Morton theatre organ. He had mixed feelings about theatre organs, and really preferred the classical instrument. In speaking of his endeavors re "opus one" he recalled:

"One night at the very beginning of the association with American (American Photplayer; ed), when I was building the two manual unit job, Mr. Werner and some of the men from Berkeley came in to examine my sample. It was much different than the classic instruments they had seen on the floor, the ones designed by Spencer. In its construction I used different contacts, key actions, chest actions and they approved it without change.

"Later on, Mr. Spencer was sent to the Fotoplayer factory in Berkeley as head of the works. He really never forgave me for siding with the American Photo Player people. Subsequently I was made superintendent of the Van Nuys plant. I never was too enthusiastic about the change and didn't want the job, but I remember so well that somebody took me aside during one of the organizational meetings -- he was a Photo Player Company man -- and told me: ' Stanley, if you don't do this somebody else will come and take over your job, and we're going to build the organ according to the model you've designed. You might just as well do it yourself. You are not being disloyal to Mr. Spencer because he is out. He just doesn't understand what we want to do.' And that was actually how I got into building the Morton.

"I had been brought up by Robert Hope-Jones on his famous unit system which I had more or less forgotten about until the change was made at Van Nuys. In looking back, I do not particularly point with pride to the unit system, but with a touch of regret because the organs that were built on the unit system in general were pretty poor things as organs. They made satisfactory noises for accompanying movies but for the rendition of music they -- well, music wasn't composed for them. It was like expecting an inferior brass band to play the great works of music.

"Anyway, the first organ I built on the unit design, a two manual instrument, eventually went into the California Theatre in Santa Barbara and stayed there for quite a long time. This was strictly an eye-opener -- to find that Wurlitzer wasn't the only firm to have a man who could design a unit orchestra."

(4 : 3)

henry f. charles

Henry F. "Cocky" Charles, salesman. A world-class salesman, "Cocky" Charles was responsible for some of the largest orders which came to the RM company, including the lucrative "exclusive" contract with Pantages. Originally from Southern California, Charles became acquainted with H.J. Werner, and was hired on as a salesman for the American Photo Player Company. When Werner became interested in producing theatre organs, but recognized that the Photo Player facility in Berkeley was ill-suited to produce them, it was Charles who advised Werner of the potential availability of the California Organ Company plant and personnel. (4 : 2)

Sales technique in the Roaring Twenties frequently involved "lengthy poker sessions, hard liquor, and at times, the services of pretty girls" (4 : 10), and "a huge capacity for drink and the ability to keep sober were prime requisites." (4 : 6)

Stanley Williams was at one point asked to train the firm's salesman "so they could talk logically about the workings of an organ.". "Most of these men called me 'Willie'. . .and requested that I refrain from telling them about pipe organ operations because, in their own words -- 'it cramps our style because now we don't know when we are lying', You can be sure I didn't waste my time trying to tell them anything after they said what they did." (4 : 6) High-pressure sales was the order of the day, and all of the major organ companies used that technique.

Sales technique in the Roaring Twenties frequently involved "lengthy poker sessions, hard liquor, and at times, the services of pretty girls" (4 : 10), and "a huge capacity for drink and the ability to keep sober were prime requisites." (4 : 6)

Stanley Williams was at one point asked to train the firm's salesman "so they could talk logically about the workings of an organ.". "Most of these men called me 'Willie'. . .and requested that I refrain from telling them about pipe organ operations because, in their own words -- 'it cramps our style because now we don't know when we are lying', You can be sure I didn't waste my time trying to tell them anything after they said what they did." (4 : 6) High-pressure sales was the order of the day, and all of the major organ companies used that technique.

robert pernod "joe" matthews

Robert Pernod "Joe" Matthews., advertising and sales; general manager. "Joe" had a musical background, previously playing piano and trombone with theatre pit orchestras until he broke his wrist. He found employment with the Eilers Music Company (as did Bell and Johnston), Joe Matthews was a canny salesman as well as a likeable and energetic administrator. He originally met H.J. Werner at the Eilers firm in San Francisco, where Matthews was selling pianos. This was just before Werner struck out on his own and started the Photo Player firm. Werner tapped Matthews to become the eastern seaboard sales representative for the company. The addition of the Robert Morton line simply gave him another tool in his sales kit.

Matthews prepared most of the trade advertising for the Photo Player firm, and both he and "Cocky" Charles were the top salesmen in the Robert Morton Company. (2: Vol.II, p. 495).

In a 1964 interview with Matthews (by Tom B'Hend, of The Console magazine), Matthews related a few anecdotes:

"We discovered C. Sharpe Minor. . .and took him out of a small cabaret in Portland to give him his first theatre organ job. I believe it was at the old Woodley Theatre in Los Angeles, which movie producer Mack Sennett had taken over and rebuilt. I recall that the Woodley had a Murray M. Harris straight classic organ installed. We removed it and put in one of the Mortons. This theatre had a large bell in the lobby and when I attended the performances there the large bell would be sounded and the patrons would head for the auditorium. In the theatre, a bright spotlight would come on and focus on the stage stairway to catch Minor as he appeared out of the wings, resplendent in full dress with a vivid red ribbon cutting across his chest. Bowing to the applause of the audience, Minor would come down to the pit, dramatically push the starter button on the console, nod to the orchestra leader, and the large orchestra and organ would crash into a mighty overture." (4 : 13)

He also remembered meeting Robert Hope-Jones on one occasion:

"I knew Hope-Jones only slightly. We corresponded about a pressure reed organ. . .with pipes and a roll-mechanism for residence organs. Hope-Jones had written Welte about using their rolls, but nothing final had been decided. He cam to New York City to see me; at that time he was still with Wurlitzer; and visited me at my home. My family were living at New Rochelle and had rented three rooms in a house there. Jones stayed overnight with us.

"I can vividly recall that we sat up all night talking. It was raining quite heavily outside. He had wanted to leave Wurlitzer and this new idea was to be his new project. He wanted me to handle it and he would act as advisor. I recall that he had gotten his shoes very wet and took them off when he arrived at the house. There was a large coal range in the kitchen and we put them in the oven. I don't think we did much about the patenting of combining reeds and pipes under pressure, but we damned near burned up his shoes!" (4 : 13)

Matthews noted that the most popular of the Morton styles that he sold were those that were six ranks and under, largely to owners of smaller theatres. Because these instruments required no external relays, they were generally less expensive.

Matthews prepared most of the trade advertising for the Photo Player firm, and both he and "Cocky" Charles were the top salesmen in the Robert Morton Company. (2: Vol.II, p. 495).

In a 1964 interview with Matthews (by Tom B'Hend, of The Console magazine), Matthews related a few anecdotes:

"We discovered C. Sharpe Minor. . .and took him out of a small cabaret in Portland to give him his first theatre organ job. I believe it was at the old Woodley Theatre in Los Angeles, which movie producer Mack Sennett had taken over and rebuilt. I recall that the Woodley had a Murray M. Harris straight classic organ installed. We removed it and put in one of the Mortons. This theatre had a large bell in the lobby and when I attended the performances there the large bell would be sounded and the patrons would head for the auditorium. In the theatre, a bright spotlight would come on and focus on the stage stairway to catch Minor as he appeared out of the wings, resplendent in full dress with a vivid red ribbon cutting across his chest. Bowing to the applause of the audience, Minor would come down to the pit, dramatically push the starter button on the console, nod to the orchestra leader, and the large orchestra and organ would crash into a mighty overture." (4 : 13)

He also remembered meeting Robert Hope-Jones on one occasion:

"I knew Hope-Jones only slightly. We corresponded about a pressure reed organ. . .with pipes and a roll-mechanism for residence organs. Hope-Jones had written Welte about using their rolls, but nothing final had been decided. He cam to New York City to see me; at that time he was still with Wurlitzer; and visited me at my home. My family were living at New Rochelle and had rented three rooms in a house there. Jones stayed overnight with us.

"I can vividly recall that we sat up all night talking. It was raining quite heavily outside. He had wanted to leave Wurlitzer and this new idea was to be his new project. He wanted me to handle it and he would act as advisor. I recall that he had gotten his shoes very wet and took them off when he arrived at the house. There was a large coal range in the kitchen and we put them in the oven. I don't think we did much about the patenting of combining reeds and pipes under pressure, but we damned near burned up his shoes!" (4 : 13)

Matthews noted that the most popular of the Morton styles that he sold were those that were six ranks and under, largely to owners of smaller theatres. Because these instruments required no external relays, they were generally less expensive.

the robert morton / the wicks connection

Very early on, perhaps even before the official incorporation of Robert Morton in 1917, Robert Morton and Wicks apparently forged an "alliance" of some sort. Bear in mind that the early Robert Morton builders plates (the "organ pipe") plate bore not only the Van Nuys factory address, but also referenced Highland, Illinois, the home of the Wicks factory. It's quite possible that there was already a deal in place between Wicks and the parent company of Robert Morton, the American Photoplayer Company in Berkeley, California.

There is nothing available to indicate whether American Photo Player may have used Wicks parts, or had some arrangement regarding technology with Wicks, but certainly it would have been a bold move to include the Highland reference on the builders' plate without some assent from Wicks, even though the name "Wicks" was not referenced. The Wicks firm was always protective of its name, image and product innovations, especially its famed "Direct Electric" (TM) action, which was trademarked and actively protected. In any event, the Wicks relationship was important to the fledgling Robert Morton Company, particularly in its early years, when chronic financial difficulties caused infrequent factory closures in Van Nuys, sometimes for several months.

It is interesting to note that although Wicks did build complete organs for Robert Morton, Robert Morton would sometimes send parts to Highland, making the organ sort of a "hybrid". This leads one to believe that if the factory was closing for a time, an organ destined for the midwest that had just entered the construction phase may have had any extant parts sitting on the Van Nuys factory floor sent to Highland for completion of the job. This would explain Wicks-built instruments with console cabinets that were clearly built in Van Nuys, or division tags, stops, keyboards, or other parts. Wicks would have been unlikely to re-tool their cabinetry shops to produce a Robert Morton duplicate console or Robert Morton electro-pneumatic windchests; it would not have been cost-effective for either company. Prior to 1925, owing to erratic cash flow and other problems, infrequent and sometimes lengthy factory closures would occur without much warning at Robert Morton, and important employees like Paul Carlsted and Stanley Williams would find employment at other firms for the "duration" when this happened. It is quite likely that Wicks may have picked up some of the slack, at least for small organs, by either building them completely in Highland, or taking over whatever construction had already begun.

It's not unlikely that Wicks would have been called upon to fill orders for small organs sold in the midwest or east, too. In order to clinch the sale and meet a deadline, it would have been far cheaper and faster to have the organ built and delivered from Highland than from Van Nuys. It's significant to note that almost all known Wicks-built Robert Mortons were small organs of 4 to 6 ranks, a size which was a staple of Robert Morton sales.

Unfortunately, at present the Robert Morton/Wicks relationship remains clouded in mystery. David Junchen, in his Encyclopedia of the American Theatre Organ, Volume II, observed the following:

"The real reason for the Robert Morton/Wicks alliance, however, was the precarious financial condition of the Van Nuys firm. Despite heavy sales, the company was teetering on the edge of insolvency and, for want of sufficient operating capital, occasionally closed its doors for a few weeks during the years 1919 - 1924. One such shutdown in 1919 lasted four months. . . .Werner's alliance with Wicks allowed sales of Robert Morton organs to continue even when he had run out of operating capital which would have allowed him to build the organs himself at a greater profit. This explains the fact that a number of Wicks-built Robert Mortons were shipped to the west coast. Despite the extra freight costs involved, Werner would rather have sold his customers Wicks-built organs than lose sales because his own nearby factory was idle." (2 : 499)

Junchen goes on to mention "the curious by-product" of the Robert Morton/Wicks affiliation, which refers to organs apparently built under the "Beethoven" nameplate. He uncovered a Wicks contract for one of these instruments which bore a cover page reading:

"Beethoven Orchestral Organ furnished by American Photo Player Company, Berkeley, distributors of Beethoven organs" (2 : 499)

This lends credence to the theory that American Photoplayer may have been pursuing a relationship with Wicks prior to the incorporation of Robert Morton, and that that relationship simply continued after Robert Morton came into being, with obvious benefits for both companies.

Further to that, Junchen notes:

"Ironically enough, Wicks' best customer for theatre organs was not a theatre chain but another organ builder, Robert Morton. The American Photo Player Company purchased about 75% of the Wicks theatre organs built between 1916 and 1923. . . .No particular attempt was made to make these Wicks-built organs look like Robert Morton products except in the nameplate design and in the percussions, which used hingeless pneumatics similar to Robert Morton designs. Otherwise, these instruments contained standard Wicks construction features throughout.

"The financial arrangement between the Robert Morton and Wicks firms remains a mystery today. . . .A curious fact relating to the Robert Morton association is that contacts for the church and theatre organs sold to them have been systematically removed from the contract file in the Wicks vault, whereas the contacts or Wicks church organs built during the same years are all intact." (2 : 695)

The actual number of organs built by Wicks for Robert Morton is unknown, with unsupported estimates ranging from 37 to 55 organs. It seems that without exception, they were all small instruments. No evidence of a three manual Wicks-built Robert Morton has ever surfaced, for instance. The arrangement appears to have ended in 1924, with the major reorganization of the Robert Morton company, and its new-found financier. There are no Wicks-built Robert Mortons known to us after 1925. (4 : 9)

Like so much of the history and output of Robert Morton, much remains to be learned, and much may be forever lost. . .except to conjecture.

There is nothing available to indicate whether American Photo Player may have used Wicks parts, or had some arrangement regarding technology with Wicks, but certainly it would have been a bold move to include the Highland reference on the builders' plate without some assent from Wicks, even though the name "Wicks" was not referenced. The Wicks firm was always protective of its name, image and product innovations, especially its famed "Direct Electric" (TM) action, which was trademarked and actively protected. In any event, the Wicks relationship was important to the fledgling Robert Morton Company, particularly in its early years, when chronic financial difficulties caused infrequent factory closures in Van Nuys, sometimes for several months.

It is interesting to note that although Wicks did build complete organs for Robert Morton, Robert Morton would sometimes send parts to Highland, making the organ sort of a "hybrid". This leads one to believe that if the factory was closing for a time, an organ destined for the midwest that had just entered the construction phase may have had any extant parts sitting on the Van Nuys factory floor sent to Highland for completion of the job. This would explain Wicks-built instruments with console cabinets that were clearly built in Van Nuys, or division tags, stops, keyboards, or other parts. Wicks would have been unlikely to re-tool their cabinetry shops to produce a Robert Morton duplicate console or Robert Morton electro-pneumatic windchests; it would not have been cost-effective for either company. Prior to 1925, owing to erratic cash flow and other problems, infrequent and sometimes lengthy factory closures would occur without much warning at Robert Morton, and important employees like Paul Carlsted and Stanley Williams would find employment at other firms for the "duration" when this happened. It is quite likely that Wicks may have picked up some of the slack, at least for small organs, by either building them completely in Highland, or taking over whatever construction had already begun.

It's not unlikely that Wicks would have been called upon to fill orders for small organs sold in the midwest or east, too. In order to clinch the sale and meet a deadline, it would have been far cheaper and faster to have the organ built and delivered from Highland than from Van Nuys. It's significant to note that almost all known Wicks-built Robert Mortons were small organs of 4 to 6 ranks, a size which was a staple of Robert Morton sales.

Unfortunately, at present the Robert Morton/Wicks relationship remains clouded in mystery. David Junchen, in his Encyclopedia of the American Theatre Organ, Volume II, observed the following:

"The real reason for the Robert Morton/Wicks alliance, however, was the precarious financial condition of the Van Nuys firm. Despite heavy sales, the company was teetering on the edge of insolvency and, for want of sufficient operating capital, occasionally closed its doors for a few weeks during the years 1919 - 1924. One such shutdown in 1919 lasted four months. . . .Werner's alliance with Wicks allowed sales of Robert Morton organs to continue even when he had run out of operating capital which would have allowed him to build the organs himself at a greater profit. This explains the fact that a number of Wicks-built Robert Mortons were shipped to the west coast. Despite the extra freight costs involved, Werner would rather have sold his customers Wicks-built organs than lose sales because his own nearby factory was idle." (2 : 499)

Junchen goes on to mention "the curious by-product" of the Robert Morton/Wicks affiliation, which refers to organs apparently built under the "Beethoven" nameplate. He uncovered a Wicks contract for one of these instruments which bore a cover page reading:

"Beethoven Orchestral Organ furnished by American Photo Player Company, Berkeley, distributors of Beethoven organs" (2 : 499)

This lends credence to the theory that American Photoplayer may have been pursuing a relationship with Wicks prior to the incorporation of Robert Morton, and that that relationship simply continued after Robert Morton came into being, with obvious benefits for both companies.

Further to that, Junchen notes:

"Ironically enough, Wicks' best customer for theatre organs was not a theatre chain but another organ builder, Robert Morton. The American Photo Player Company purchased about 75% of the Wicks theatre organs built between 1916 and 1923. . . .No particular attempt was made to make these Wicks-built organs look like Robert Morton products except in the nameplate design and in the percussions, which used hingeless pneumatics similar to Robert Morton designs. Otherwise, these instruments contained standard Wicks construction features throughout.

"The financial arrangement between the Robert Morton and Wicks firms remains a mystery today. . . .A curious fact relating to the Robert Morton association is that contacts for the church and theatre organs sold to them have been systematically removed from the contract file in the Wicks vault, whereas the contacts or Wicks church organs built during the same years are all intact." (2 : 695)

The actual number of organs built by Wicks for Robert Morton is unknown, with unsupported estimates ranging from 37 to 55 organs. It seems that without exception, they were all small instruments. No evidence of a three manual Wicks-built Robert Morton has ever surfaced, for instance. The arrangement appears to have ended in 1924, with the major reorganization of the Robert Morton company, and its new-found financier. There are no Wicks-built Robert Mortons known to us after 1925. (4 : 9)

Like so much of the history and output of Robert Morton, much remains to be learned, and much may be forever lost. . .except to conjecture.

wicks-built robert mortons

Here are some examples of the organs built by Wicks under the Robert Morton name. You will note that some of these instruments bear consoles which were clearly built in Van Nuys, but that pipework, windchest and mechanicals are definitely Wicks' product. Additionally, some consoles clearly built by Wicks bear Robert Morton "flourishes", such as division labels, stops, keyboards or other details. It doesn't appear that Robert Morton shipped pipework or chestwork to Wicks, which would have been counterproductive, but this is only logical conjecture.

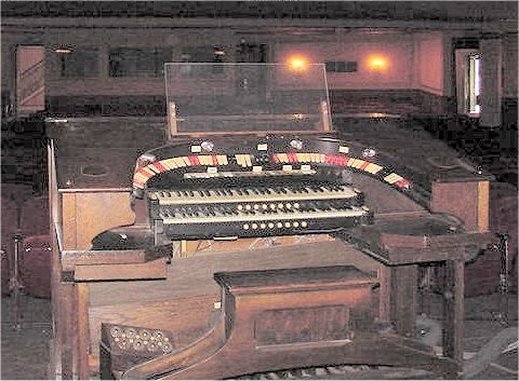

The console at left was originally a theatre organ, but found its way into a mortuary, losing its traps and percussions (thus the missing stops). The stops and keyboards are Wicks, but the division tags are unquestionably Robert Morton. The console style and internal mechanisms are also Wicks, rather than Robert Morton. The meters in the ratguards were a Wicks feature. This organ had an external Wicks relay, and was a four rank instrument.

The console at left was originally a theatre organ, but found its way into a mortuary, losing its traps and percussions (thus the missing stops). The stops and keyboards are Wicks, but the division tags are unquestionably Robert Morton. The console style and internal mechanisms are also Wicks, rather than Robert Morton. The meters in the ratguards were a Wicks feature. This organ had an external Wicks relay, and was a four rank instrument.

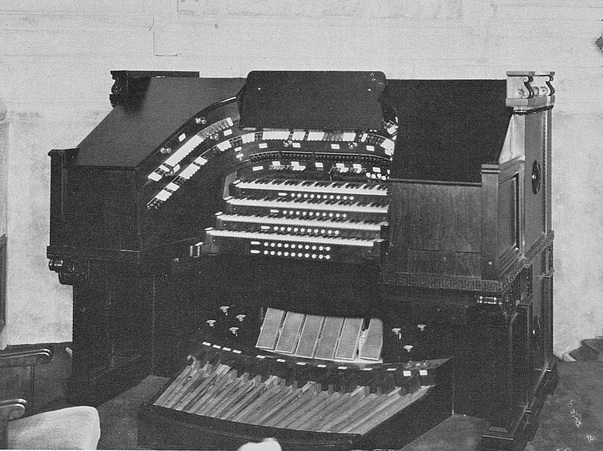

Magnum OpusES -- THE BOVARD AUDITORIUM

Since the early days of the Murray Harris firm, the company built organs primarily for churches. With the advent of the Robert Morton organ and the emphasis on theatre pipe organ production, church organ building did not cease.

The largest instrument produced under the Robert Morton banner was built in 1920 for the Bovard Auditorium on the campus of the University of Southern California. This four-manual instrument boasted the only two 32' stop built by the company; a 32' Bombarde, and a 32' Contra Bourdon (now located in the organ of the former Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California). Although it had a horseshoe console, it was a straight organ of 85 ranks, with little or no unification. It was dedicated by Edwin H. Lemare (pictured), the famous organist, transcriptionist and composer. This organ was dismantled and dispersed in the 1960s. (see also entry in "Gallery section)

The largest instrument produced under the Robert Morton banner was built in 1920 for the Bovard Auditorium on the campus of the University of Southern California. This four-manual instrument boasted the only two 32' stop built by the company; a 32' Bombarde, and a 32' Contra Bourdon (now located in the organ of the former Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove, California). Although it had a horseshoe console, it was a straight organ of 85 ranks, with little or no unification. It was dedicated by Edwin H. Lemare (pictured), the famous organist, transcriptionist and composer. This organ was dismantled and dispersed in the 1960s. (see also entry in "Gallery section)

THE ELKS 99 LODGE ORGAN

In 1926, Los Angeles Elks Lodge number 99 ordered a massive four manual, 61 rank organ with an antiphonal division and a second console. This instrument was not strictly a theatre organ, although it was outfitted to play a broad variety of music. It had several unit stops, but was largely a "straight" configuration. This was the second largest of the organs produced under the Robert Morton banner.

The two manual console was situated on the large landing of the Grand Staircase, outside of the large lodge meeting room. The antiphonal division, which was playable from either console, had a set of swell shades which spoke into the landing and staircase area, and could certainly be heard in the expansive foyer.

This is one of perhaps two Robert Morton instruments which featured a second console. Unfortunately, the fate of the organ is dependent upon the fate of the building, and the Elks Lodge has, at various times over the decades, been a lodge, a hotel (more than one brand), a specialty rental hall, a popular movie location, and recent events have once again put it back into line for repurposing, but this time -- without the organ. The organ, which had received significant damage over the years, has been dismantled and dispersed.

The two manual console was situated on the large landing of the Grand Staircase, outside of the large lodge meeting room. The antiphonal division, which was playable from either console, had a set of swell shades which spoke into the landing and staircase area, and could certainly be heard in the expansive foyer.

This is one of perhaps two Robert Morton instruments which featured a second console. Unfortunately, the fate of the organ is dependent upon the fate of the building, and the Elks Lodge has, at various times over the decades, been a lodge, a hotel (more than one brand), a specialty rental hall, a popular movie location, and recent events have once again put it back into line for repurposing, but this time -- without the organ. The organ, which had received significant damage over the years, has been dismantled and dispersed.

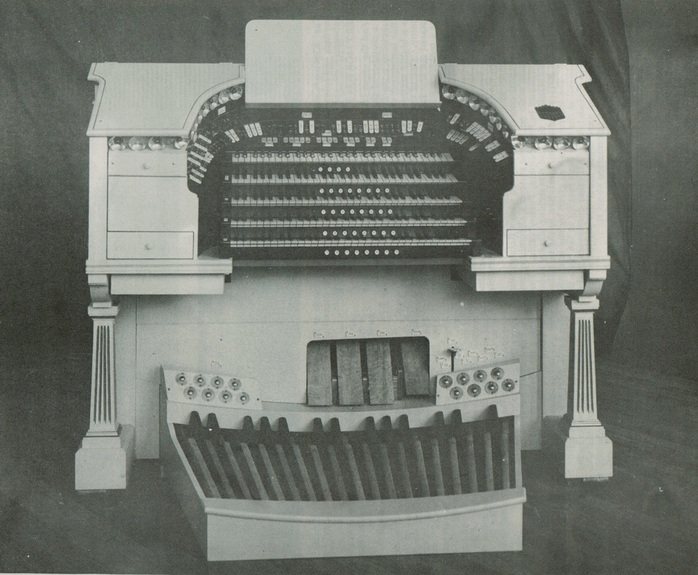

The Five Manual Organs

It seems that the "crowning glory" of most theatre organ builders were their four and five-manual instruments, especially the five deckers. Interestingly, usually the largest instruments produced by a builder were coupled to four manual consoles, rather than five, like Wurlitzer's Radio City Music Hall organ (although Barton's largest was six!) As mentioned, Robert Morton's largest instrument was a four-manual organ of either 72 or 85 ranks, but with a classical specification (and a horseshoe console).

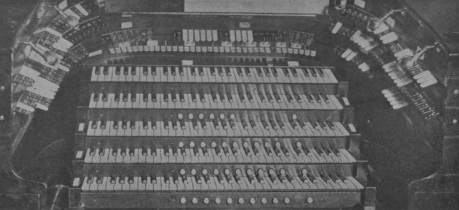

Robert Morton did produce a few five manual organs, but it seems that only one was of significant size in terms of resources. Very little is actually known about these organs, but it appears that three of these were for instruments that went into theatres and perhaps one was simply a display console for the sales floor at the factory.

Robert Morton did produce a few five manual organs, but it seems that only one was of significant size in terms of resources. Very little is actually known about these organs, but it appears that three of these were for instruments that went into theatres and perhaps one was simply a display console for the sales floor at the factory.

Palm Theatre, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

This 1921 organ is the first of the five-manual instruments produced by Robert Morton. With a 10 horsepower blower to wind it, it may have had impressive resources, but there is no indication of how many ranks it had. The number of stops in the stoprail would suggest that it perhaps had a number of "Straight" ranks in addition to its unified ranks, thus relying upon couplers and requiring fewer stops.

It has been argued that this photo portrays the "salesroom floor" demo console, but nothing has been advanced to substantiate that claim, or to show that the demo organ actually existed.

We have no specification for this instrument.

It is reported that this organ was dismantled and dispersed many years ago.

It has been argued that this photo portrays the "salesroom floor" demo console, but nothing has been advanced to substantiate that claim, or to show that the demo organ actually existed.

We have no specification for this instrument.

It is reported that this organ was dismantled and dispersed many years ago.

There is some speculation that this organ console was simply a mannequin, not intended for any purpose than as a sales prop, and that as time went on it was stripped of its components for use in other organs. This seems unlikely, since a smaller "dummy" instrument would have been easier and cheaper to construct, and money was always an issue at Robert Morton.

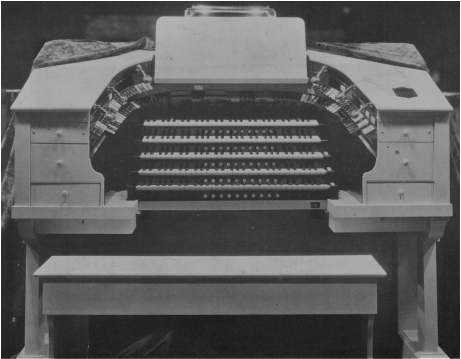

Kinema Theatre, Fresno, California

Also in 1921, a smaller five manual instrument was shipped to the Kinema Theatre in Fresno, California. Based upon its 7 1/2 horsepower blower, this organ was likely to have been about 10 ranks or so.

The theatre opened in 1914, and was equipped with an organ which may have been a product of the Johnston or California Organ era of Robert Morton. That makes perfect sense, since the new Robert Morton Company would have been looking to stimulate its business by selling "upgrades" to its previous customers and contacts. It is reliably reported that the specification of the new five-manual instrumennt was similar to a standard 3/12 Robert Morton of that era, probably with a number of straight ranks, and the two upper manuals were coupler manuals. It is quite possible that the pipes and mechanism from the previous instrument may have been re-used in the rebuild.

The organ was removed from the building at some point, and sold to someone in the Oakland, California area. The console was apparently broken up for parts.

The theatre opened in 1914, and was equipped with an organ which may have been a product of the Johnston or California Organ era of Robert Morton. That makes perfect sense, since the new Robert Morton Company would have been looking to stimulate its business by selling "upgrades" to its previous customers and contacts. It is reliably reported that the specification of the new five-manual instrumennt was similar to a standard 3/12 Robert Morton of that era, probably with a number of straight ranks, and the two upper manuals were coupler manuals. It is quite possible that the pipes and mechanism from the previous instrument may have been re-used in the rebuild.

The organ was removed from the building at some point, and sold to someone in the Oakland, California area. The console was apparently broken up for parts.

Kinema Theatre, Los Angeles, California

The magnum opus of Robert Morton theatre organs, the Kinema organ started as a 3 manual instrument installed in the theatre in 1920, and then was enlarged to perhaps 28 ranks in 1923, with a new five manual console, and a four rank Echo organ.

This behemoth, powered by a 30 horsepower blower rated at 15", was one of the first high-pressure Robert Morton organs. Fifteen inches of wind pressure would become a Robert Morton standard by 1928. The Kinema organ fell on hard times when a theatre fire destroyed the console. The remainder of the organ was dismantled and dispersed, with a good deal of pipework going into the organ at Trinity Methodist Church in downtown Los Angeles (which is also now gone).

This behemoth, powered by a 30 horsepower blower rated at 15", was one of the first high-pressure Robert Morton organs. Fifteen inches of wind pressure would become a Robert Morton standard by 1928. The Kinema organ fell on hard times when a theatre fire destroyed the console. The remainder of the organ was dismantled and dispersed, with a good deal of pipework going into the organ at Trinity Methodist Church in downtown Los Angeles (which is also now gone).

The "Wonder Mortons"

In the same way that the Wurlitzer brand created its "flagship" organs in the famous "Fox Special", four manual, 36 rank instruments, the Robert Morton Company also produced a top-of-the-line series of instruments which collectively became known as the "Wonder Mortons". In both cases, the design of the organ was unique to the particular chain of theatres into which they were installed. The Wurlitzer 4/36 organs (frequently, if erroneously, referred to as "Crawford Specials", after famous theatre organist Jesse Crawford) were all installed in Fox's greatest theatres, in San Francisco, St. Louis, Detroit and Brooklyn. The first of these organs, interestingly, was installed in the Paramount Theatre in New York -- not a part of the Fox chain.

The "flagship" Robert Morton organs came to be known as "Wonder Mortons", not because the were so-named by the company, but because they all went into the Loew's "Wonder Theatres", the greatest of the theatres in their chain. All except for the first, that is -- which was installed in the New Orleans Saenger Theatre (and remains there, dormant, today). The New Orleans Saenger organ broke new ground for Robert Morton in the same way that the New York Paramount organ broke new ground for Wurlitzer.

Robert Morton did very good business with both the Pantages and Loew's theatre chains, and when the Loew's Theatre circuit set about to create the biggest and best theatres in their circuit, they wanted Robert Morton to create the biggest and best organs for those theatres.

The five "Wonder Mortons" were installed in these Loew's theatres:

Valencia Theatre, in Jamaica (1928) (Now in the Balboa Theatre, San Diego, California)

Paradise Theatre, in the Bronx (1929) (Now in the Jersey Theatre, Jersy City, New Jersey)

Kings Theatre, in Brooklyn (1929) (largely dismantled and dispersed)

Loew's Jersey Theatre, in Jersey City (1929)

175th Street Theatre, in Manhattan (1930) (Still installed in theatre, but unplayable)

The first and most striking difference in the Wonder Mortons were their distinctive console design, unlike anything else that the company had produced. Although the "fence-top" design is associated with these instruments, ironically, the inspiration for the design came from a competitor -- Barton, of Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The Indiana Theatre, in Indianapolis, housed a three manual instrument of 17 ranks (now in the Warren Peforming Arts Center in Indianapolis) which utilized a decorative "fence" around the top of the console, along with "shield/coat of arms" decor on the sides and large, decorative corbels. While the source of the Robert Morton design is unmistakable here, it becomes a matter of some creative speculation to sleuth how the connection came about. Two potential sources come to mind, and they may have both conspired to adopt this design for the Wonder Mortons.

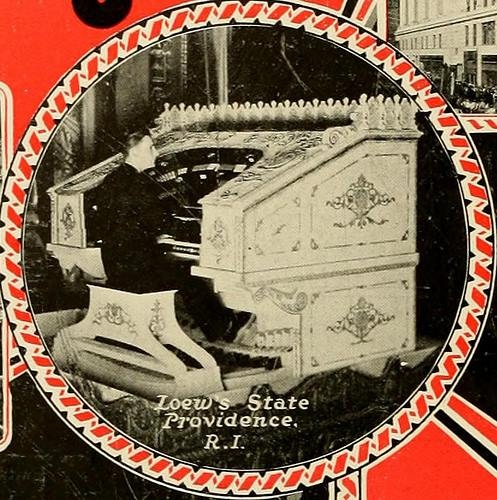

Organist Maurice Cook was employed by the Indiana Theatre for a time, and he also presided at the first Robert Morton to bear the fabled fence design, a 20 rank organ in Loew's State Theatre, in Providence, Rhode Island. Joe Matthews would also have likely been involved in this process, as a "salesman without portfolio" for the company. He kept abreast of what their competitors were doing, and in arriving at a contract for the Loew's organ, may have been influenced by both organist Cook, and what he saw in theatres during his sales tours through the Midwest and the South. Since he apparently was suitably impressed by Barton's "innovation", when a striking console design was desired for the Loew's "Wonder" theatres, this design may have come immediately to mind.

There were five Wonder Mortons built, not including the original prototype, the New Orleans Saenger Theatre instrument. All consisted of essentially the same 23 rank specification (please refer to the "Specification" section for details), on four manuals and pedal, and all featured the new decorative scheme discussed above. The /////

FEATURE ARTICLE -- "The wonder morton means more-tone" by clark wilson

(Article reproduced with permission of the author)

The in-depth article on the Wonder Morton organs in the recent issue of the THEATRE ORGAN was a most enjoyable one. Obviously a labor of love, it is indeed an overdue look at some extremely fine and well-built instruments. There are a few errors of fact that crept in that ought to be corrected, and some additional things added in a publication such as ours that will likely be looked at in the future as a reference source. It is important that we strive to keep the details concerning these organs as accurate as humanly possible. Even now it can be quite difficult to ascertain absolutes about some instruments.

For instance, the only one of the "big" Robert Morton organs still playing in its original home is in the Ohio Theatre in Columbus. While additions have been made around the original organ, the core 20 ranks and related mechanicals and wind systems remain untouched, both physically and tonally, and this is the only place that one can presently go to hear exactly what Morton produced and intended in their largest showcase instruments.

"Wonder Organ" was a moniker attached to two companies -- Morton and Kilgen, the latter having first dibs and utilizing it heavily in advertising. Actually, the Morton term is derived from the names of the theatres in which the organs were installed: the Loew's Wonder Theatres in greater New York. Terming them "Wonder Mortons" might actually be somewhat akin to calling the large Wurlitzers "Fox Specials", a name unused by that company but popular in our conscience. While there may also have been some local advertisement of Bartons by their owners in that way (almost every type organ was called a wonder organ at one time or another), the Barton Company's slogan was the well-known "Golden Voiced Barton."

Interestingly enough, the earliest known decorative console with a fence around the top was a Barton, that of the Indiana Theatre in Indianapolis (pictured above). It came first, and comparisons with the later Morton consoles are inevitable. They are basically dead ringers for the Morton design. A possible common denominator in these instances may have been one Maurice Cook (who, ironically, was occasionally billed as a wonder organist), a very popular player who was at the Indiana and also later at the first Morton with a very similar fence: the 20-rank job in Loew's Providence, This might bear some more research, as we still don't really know the absolute connection between the consoles with fences. And hence, on to the Wonder Organs.

Tonally, the large, late Mortons were powerhouses. The company intended to give Loew's as much "bang for the buck" as possible and standardized on large and especially high wind pressures throughout, making the organs more than equal to the task of filling 3,000 seats for solo, orchestra, or picture work. Their output is probably at least 35% greater than a comparable Wurlitzer makeup would have been, and it's telling to hear just how weak a 10" rank of Wurlitzer pipes is when standing beside the equivalent Morton sets.

Today, several of these organs have been significantly tonally altered, which has resulted in a sound not exactly as the factory would have put out. Back in the 80's when the Santa Barbara Arlington job was done, the powers that be wished for it to sound more as a Wurlitzer, so much of the pipework was revoiced and re-regulated (read "softened"), sometimes on lower wind or with lids attached to potent ranks, such as the Krumet. This scribe knows: he was retained and paid to do the work at the Newton shop in San Jose and at the theatre. The resulting sound is grand indeed, but not definitive or original Morton.

The nine big Mortons -- four at 20 ranks (the Loew's Ohio, Midland, Penn, and Providence), five at 23 ranks -- were all voiced identically and separated by only three ranks: a second Tibia Clausa, Krumet and French Horn. They had an individual and spectacularly identifiable sound. A 25-hp Spencer blower was provided giving more than a horse per rank! All manual ranks save the Vox Humanas were voiced on 15" wind (including Tibias and English Horn), several of the 16' basses in the Solo side were on 20", the Solo Vox (often made by National Organ Supply) was on 12"and the Main Vox was on 8". An interesting and common Morton practice was that of placing the "power" basses -- usually Diaphone and Tuba -- on 5" higher wind than the manual pipework.

While the Vox ranks are indeed ethereal compared to the rest of the instrument, they are not in any way deficient or weak and stand very well in any Tibia, string, or ensemble combinations.

The Morton strings are probably the sharpest strings of any manufacturer, for which the company is/was justifiably known. Each of the sets (Violins, Gamba and Salicional) display much "rosin" and edge and combine into the most colorful and orchestral of string ensembles. As originally voiced, they need no help from any other flue ranks present and sound nothing like Kimball strings, which are typically larger in scale and of a slightly more suave nature..